Historical Imagination and Alternatives to the Schlieffen Plan

And Why It's Worth Remembering Yesterday's Tomorrow

“An enveloping movement can only be justified by a general superiority or by the superiority of our lines of communication and retreat to those of our enemy; flank positions are also conditional on the same circumstances; every attack weakens as it advances.”

-Carl von Clausewitz

As a tool for understanding the past, alternative history has something of a bad name. This is understandable given its prevalence in speculative fiction. However, imagining different pasts is essential for understanding history as it actually happened and avoiding reading a sense of inevitability into the course of events. Resisting a sense of inevitability is crucial to understanding the past because the people of the past saw their future as contingent. To them, at that time, what we know as history was merely one of many possibilities. Empathizing with them means imagining pasts that never were, which for the people of the past were futures that were causes of hope and fear. This empathy allows us to contextualize their actions, to understand what they strove for or fought against in their own terms, rather than rationalizing those motivations in light of outcomes that were not then known.

The First World War is a useful case to examine in this respect for a number of reasons. It had an immediate cause that was largely coincidental in the sense that the assassination of Franz Ferdinand cannot be considered an inevitability, nor can the escalation to a general European war. The ensuing “July Crisis” was not the first crisis between the European power blocs, yet it produced a conflagration of apocalyptic proportions, seemingly despite the desires of the participants. We will make the case that the Schlieffen Plan1 was not the only option available to Germany and the fixation on it greatly influenced the shape of the war—not necessarily to Germany’s advantage. We will first demonstrate that there were in fact alternatives available and subsequently examine the motivations for the rejection of them and the ensuing historical consequences. Through this investigation, we will see the contingency of historical events even on the grand scale, despite the continuous action of the forces that underlie them.

The Power of the Defensive and the Cult of the Offensive

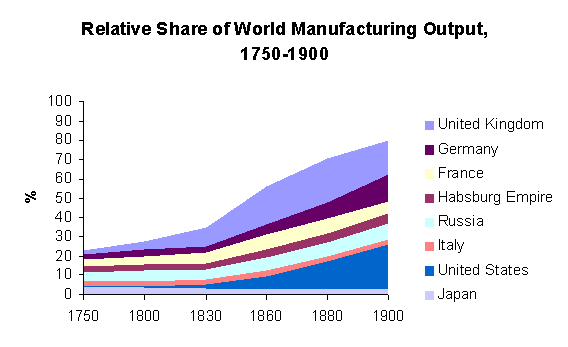

To begin, it’s necessary to look at the changes in the character of war that were evident throughout the latter part of the 19th century, namely: the increased effectiveness of firepower and the increased size of armies. The former made attacking successfully more difficult and more costly, even when successful; the latter meant maneuvering required more geographical space. To elaborate on the latter: the greater size of armies, combined with the greater mobility afforded by the proliferation of rail, meant armies were not discrete points, as they had been through the Napoleonic era, but spanned the entire front line. Battles became much less discretely defined than they were in previous wars. This produced essentially continuous contact between opposing armies which could use railroads to redistribute forces along the front depending on where the other side was concentrating its efforts. Breakthrough became the prerequisite of maneuver.

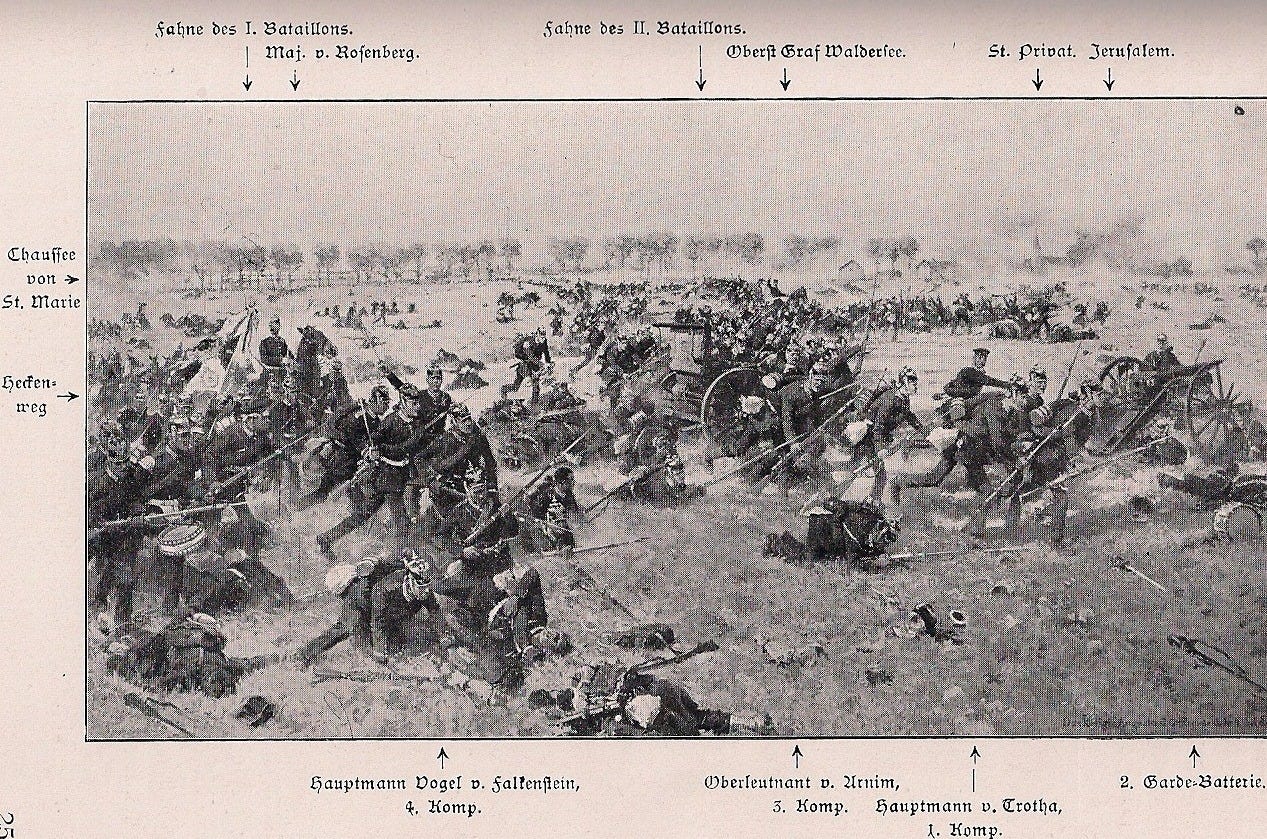

These developments were not perceivable only in hindsight. Germany’s last great power war, the Franco-Prussian war, had shown many of these trends, even if they had mostly been overcome. The brutal casualties at Mars le Tours and St. Privat were genuinely traumatic demonstrations of the effects of modern firepower. The ultimate victory can be attributed to the fact that the Germans had fought well, but it was no less important that the French had fought quite poorly. Just as every Cannae requires its Varro as much as its Hannibal, so too did the great victory Sedan require a Napoleon III as much as it did the Elder Moltke. Reproducing that success could not be guaranteed because there is no means to ensure the incompetence of the other side. Had the victory in the Franco-Prussian war been rightly understood as exceptional, the implications of these developments might have been more correctly understood, and German war plans might not have been premised on recapturing lightning in a bottle.

Likewise, less chauvinism in the evaluation of the Russo-Japanese war might have provided the Germans with a very clear understanding of the power of the contemporary tactical defensive. The defensive, in fact, had remained the stronger form of war, undermining one of the assumptions on which the Schlieffen Plan was based. This fact is not evident only through hindsight; both Clausewitz and the Elder Moltke clearly stated this. The advances in gunnery and firearms that made the battlefield so deadly merely reinforced an existing state of affairs—they did not fundamentally alter the relationship between the attack and defensive.

Two Cults

Against the recognition of these developments was the “cult of the offensive.” But when we speak of the cult of the offensive in the German context, we are really speaking of two things. The first is common to Europe: the conviction of the superiority of cold steel to hot lead, of the moral advantages of the attacker, as well as the benefits of initiative, surprise, and concentration, etc. The second, however, is the belief that Germany’s precarious strategic situation could only be remedied (if it came to war) by a swift and decisive offensive in one direction. As Schlieffen’s focus came to be on France (partially due to Russian irrelevance in the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War), this “do or die” offensive became synonymous with the Schlieffen Plan as it is popularly understood. This context is important because when discussing alternatives to the Schlieffen Plan it must be established whether these assumptions are true or at least accepted for the purposes of the hypothetical.

We have already addressed the reasons the tactical superiority of the defensive ought to have been understood. But what of the second impetus to the offensive, the need for a “knock-out” against one of Germany’s foes? It must be admitted that in a central position facing two foes, there is a clear logic to falling upon them one at a time to prevent their joining, fighting two battles each against similarly strong opponents rather than a single one against a combined, superior foe. This is where Germany’s peculiar idea of a “preventative war” originates. Preventive war is a distinct concept from preemptive war, which refers to declaring war on another state on the grounds that they are going to imminently attack, e.g. one state sees another start massing forces for an attack and declares war before the other can. Preventative war, on the other hand, does not involve any immediate threat, merely the prospect of war. In this case, the Germans feared that as Russia modernized, it would no longer be able to win a war against the Entente. As such, the General Staff in particular became increasingly convinced that a war needed to be fought against the Entente while it remained possible to do so, else Germany would be vulnerable to threats or outright invasion. This is where a second, peculiarly German cult of the offensive originates.

In this respect, the influence of the more general form of the cult of the offensive is as an accelerant: if Germany needed to defeat the Entente before demographics made that impossible, it only made sense to make use of the advantages of the attacker. The falseness of the cult of the offensive is therefore very significant for evaluating the Schlieffen Plan; as we recognize that the defensive remained the superior form of war, the idea of attacking from fear of being attacked becomes an absurdity. Further, a clear appreciation of the strategic balance makes clear that there was no serious danger of the Entente winning a war of aggression against Germany. Germany’s strength was such that by availing itself of the advantages of the defender it was well positioned to utterly deny its enemies any success, even should the Russians prove extremely successful in their modernization. As such, the falseness of the first cult weakens the already flawed case of the second.

The Ends and the General Staff

In all this there is still missing the fact that war does not fall upon nations like an errant thunderbolt on the divinely disfavored. Outside of general political aims that might motivate war, there is an immediate political cause, a crisis that frames it. For instance, WWI’s immediate cause was the assassination of the Hapsburg heir by Serbian-backed separatists. The crisis expanded and drew in Germany as it was obliged to defend Austria-Hungary from Russia (which sought to protect Serbia). This course of events logically called for a German counter-offensive against Russia to protect Austria-Hungary as it in turn sought to invade Serbia. Instead, Germany invaded Belgium, something which Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg struggled to explain even to the Reichstag. The infamously strict mobilization timeline of the Schlieffen Plan meant that Germany was obliged to attack France, regardless of what was actually at issue in the crisis.

States typically draft a series of war plans for various contingencies specifically to avoid this kind of absurdity and embarrassment. It would have been equally strange had the crisis that brought war occurred in the West and the only up-to-date plan had forced a strike against Russia. But German planning was captured by a fixation on total victory (“absolute destruction” as Isabel Hull’s book on Imperial German military culture is titled). Considering the strength of the alliance opposing Germany, total victory was a tall order, and justified otherwise absurd gambles. For this reason, Aufmarsch Ost, the plan for a war directed against Russia alone had been allowed to become outdated. The strengthening of the Entente had made a war against only Russia inconceivable and directing the first blow of the war east could not promise the total victory the General Staff sought.

From this point of view, abandoning Aufmarsch Ost had a clear logic: the Schlieffen Plan was the only war plan that could offer a chance of total victory. The French Army was more modern than the Russian army and faster to mobilize. If total victory on both fronts was the objective, using the advantages of speedy mobilization to gain victory over the French gave the Germans good odds in a stand-up fight against the Russians. Poor infrastructure in the East and the strategic depth of Russia also ruled out a rapid decision in the East. Paris was simply closer than Moscow and the loss of East Prussia preferable to risking the Ruhr. More importantly, by the time the Russians would be defeated, the Western Front, being so narrow, would be densely manned and Belgium fully mobilized. The Schlieffen Plan would not be possible in such circumstances. There was no clear way of achieving total victory in the West if it was not sought within the opening days of war.

Problems with the Premise

The Invisible Rubicon

The first problem was that by aiming at total victory and relying on superior mobilization speed the General Staff seriously limited the room of diplomacy to maneuver. The machine could not be spun up, held ready while negotiations occurred, and then wound down if matters were settled. Instead, when the winding up started, if there was no settlement immediately forthcoming, there was a choice between war and helplessness (the invalidation of the only operational plan). The short window for negotiations, like the Doomsday Machine from the movie Dr. Strangelove, had no value because the other side was completely unaware of it. The failure to determine what “victory” might actually mean and the failure to subordinate the planning of the General Staff to statecraft meant that German actions appeared to other states as entirely erratic, incomprehensible, or even maniacally aggressive. This not only made it more difficult to resolve a crisis, but reduced the possibility of a negotiated settlement in war, as we will later discuss.

False Urgency

The July Crisis was not the first crisis to occur between the alliance blocs. Others had been defused when the choice was made to prefer dissatisfaction to war. What was different this time was that the Schlieffen Plan was nearing its expiration date. The whole strategy relied on a tactical action that only stood a chance of success if executed very early (namely overrunning Belgian fortifications before they could be fully manned). At the same time, Russian modernization meant the window to win on one front before turning to the other was shrinking year-by-year. The attitude of the German General Staff was that war was preferable to giving up the Schlieffen Plan based on the premise that total victory was the only kind.

They did not believe they had the political authority to aim at a lower objective and there was no institution authorized to provide their war plans with anything more concrete to aim at. If a clearer metric for success had been provided, the Schlieffen Plan would have lost much of its appeal, as its risks would no longer appear as tolerable by necessity. Of course, political authority would have the right to choose such a risky course, but German designs on France and Russia were too vague to provide the conviction necessary for such a gamble. The General Staff, in its effort to fulfill its self-conception of being outside of politics, did not consider the question of what kind of peace the politicians might be satisfied with and instead sought the absolute destruction of the enemy axiomatically, such that they might be rendered helpless.

Magnitude Against Likelihood

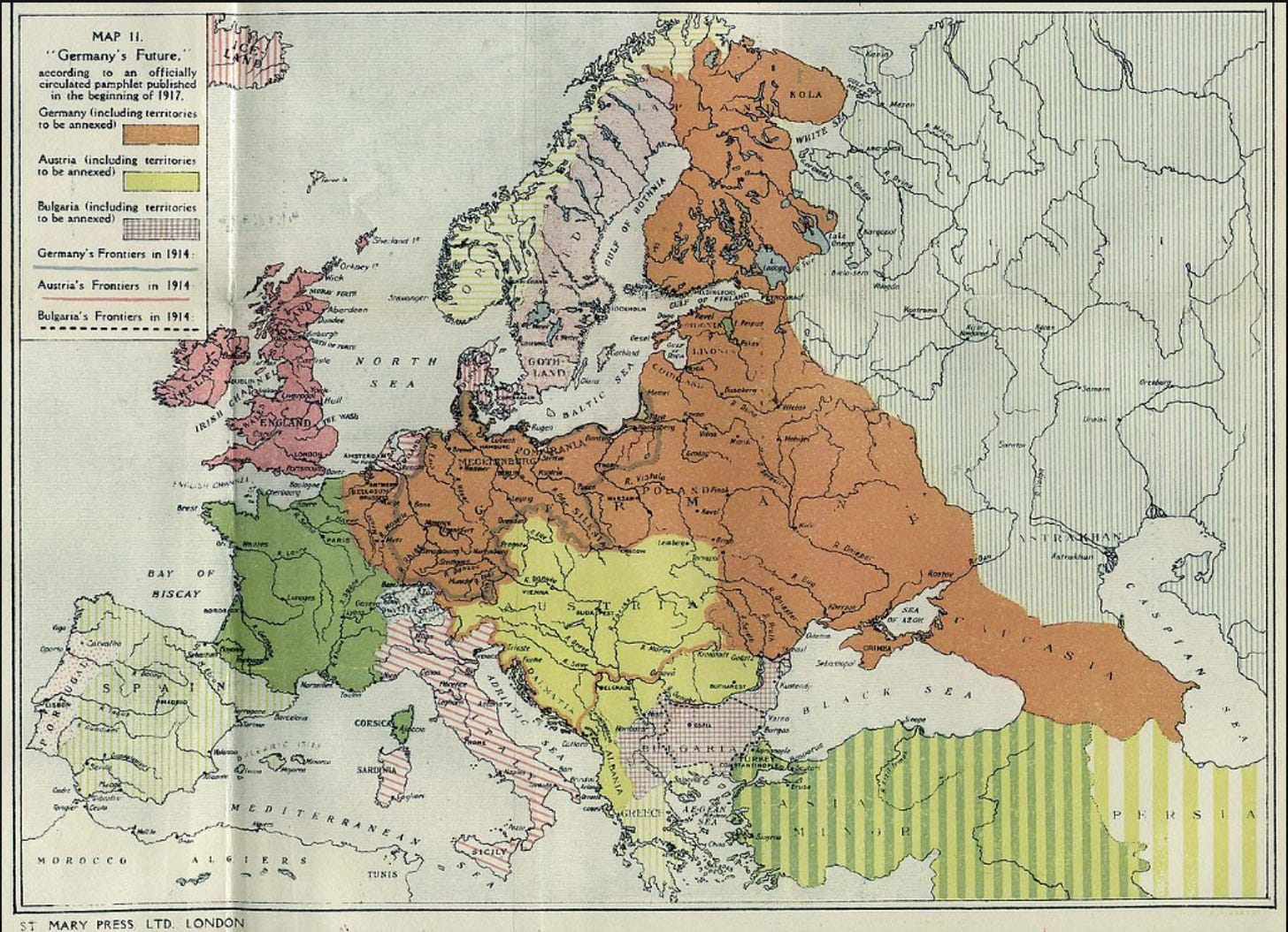

Another element is that increasing the odds of total victory may mean reducing the odds of “ordinary victory” and often means increasing the odds of disaster. Germany did not meet total disaster in 1914, but it did meet a major one. It found itself in an attritional struggle with an alliance vastly superior in men and materiel. Its masterstroke had faltered and there was no plan for what next. At the same time, Germany faced a near total blockade.

Some of these factors were inevitable characteristics of a war with the Entente. Many, however, are a product of the prioritization of total victory axiomatically. If German aims were aligned with the Septemberprogramm and Germany was therefore willing to accept the risks of such vast ambitions, then the Schlieffen Plan was justified. However, if lesser objectives could be sufficient, then achieving ordinary victories (even if primarily defensively) could be enough to avoid disaster and gain some kind of victory. While war originates from political conditions, it naturally affects them by its initiation and so it is typically easier to avoid a war than to end one. Nevertheless, the strategic situation in this case made the possibility of a limited war likelier than one might think.

The July Crisis resulting in only a “small war” seems unimaginable in retrospect—yet there was considerable hope placed in this idea. German industry certainly hoped it would not get beyond that, as did the British. The fact that it was not localized is usually attributed to the alliance structure. Russia supported Serbia, and so Germany supported Austria-Hungary against Russia, which in turn brought about French and British involvement. This is not untrue, but an overly mechanistic framing. Alliances do not function like clockwork. The Russians had to choose to back the Serbians even at the cost of a European war, the French and British had to choose to stand behind the Russian gamble, and, of course, the Germans had to continue to back the Austrians as a war seemed likely.

From this, we can see that there were a number of likely “off-ramps” for the crisis, either before war broke out, or shortly after. The Germans could have pressured the Austrians to compromise and accept an international conference to settle the fate of Serbia. Or else the Russians might have been pressured by the French and British not to start a war with Germany or itself refrained out of fear that public opinion in its allies would not permit their participation in a war over Serbia.

Once war broke out, there were still a number of options for limiting the scale of the conflict. If Austria-Hungary had managed to swiftly invade Serbia and present Russia a fait accompli before it managed to mobilize for war, the war may have remained localized. Likewise, had the Germans not attacked in the West, they would have likely inflicted serious losses on the Russians, considering their organizational superiority and the availability of forces that otherwise would have been allocated to the Schlieffen Plan. Following this battle, there would likely be an opportunity to make peace if the Germans were inclined to offer moderate terms; the Russians would be in grave danger and their allies would be unable to do more than conduct fruitless attacks into German fortifications.

The nature of the Schlieffen Plan foreclosed these opportunities. As mentioned, it artificially limited the scope for negotiation, and its narrow definition of victory created a false sense of impending doom for Germany. The violation of Belgian sovereignty stirred up international outrage and the attack towards Paris inflamed the French people for a mortal struggle. The Entente could see good odds of inflicting a serious defeat upon the Germans, and neither side wished their sunk costs to be for naught. The Schlieffen Plan, in its failure to actually knock the French out of the war, united the Entente rather than divide it, as other courses of action might have done. The French were capable of occupying the bulk of Germany’s strength while Russia could just about manage the limited German forces that were assisting Austria-Hungary. In its failure to think on the political level, the German General Staff failed to make use of Germany’s central position between the members of the Entente to create political problems for the alliance that would make a favorable peace more likely.

A Means Without an End

If we are not to take the perspective of the German General Staff in approaching the question from a purely military standpoint, it is necessary to look at the political-strategic questions. That is to say, when asking whether Germany should have struck East or West in 1914, we should ask: what does Germany hope to gain by this? In Clausewitz’s terms, what is the political purpose from which military action was to derive its goal? For, as he writes, “it is impossible to conceive of a means without an end.”

Secretary of Defense Rock and I have written a two part series exploring why Germany was incapable of functioning on the strategic level and answering these questions on its own. In short, a constellation of factors undermined civil-military relations in the German Empire. The Kaiser had succeeded in centralizing power and creating a personalist system, but this in turn meant he was responsible for coordinating political and military bodies in an overall grand strategy. The Kaiser’s capriciousness and indolence were thus a fatal problem in themselves but perhaps worse than that was the polycratic system this produced. In practice, ministers could do as they wished, regardless of the policy of the chancellor, so long as they had the confidence of the Kaiser. Each man had his own worldview and his own understanding of what was in Germany’s interest, which was not subordinated to any comprehensive strategy.

This provides us with a fundamental challenge for evaluating courses of action: there is no clear definition of victory. If the Kaiser had called a council of the heads of the army, navy, foreign ministry, etc. to determine Germany’s aims—minimum and maximum—there would be a clear metric by which we could judge prospective campaign plans. Therefore, we are left with something of a trilemma, do we judge:

1. By the fixation of the General Staff on “absolute destruction”

2. By the vague and various goals of expanding German power and gaining its “place in the sun” or

3. By Germany’s actual national interest (as much as such a thing exists)?

Defining Victory for the Purposes of Our Investigation

As Chief of the General Staff from 1857-1888, Helmuth von Moltke the Elder justified an axiomatic focus on total victory on the grounds that politicians reserved the right to revise the aims of a war up or down. As such, war plans ought to aim at the total defeat of the enemy on the basis that if the politicians desire to extract more concessions from the enemy, expanding the margin of victory ad hoc to accommodate these new objectives would be difficult, costly, and risky.2 Perceptive readers may have noticed that while Moltke is giving lip service to the primacy of policy, he’s actually rejecting the idea that military operations should give any consideration to the immediate goals expressed by politicians, and they should instead seek total victory axiomatically.

Aside from directly contradicting Clausewitz (whom Moltke popularized), Moltke’s reasoning is extremely tenuous: if the politicians begin the war seeking a lesser objective and choose to then seek a higher one, they could simply be informed of the limitations and difficulties involved in increasing the scope of the war at the outset, and choose what level of risk they were willing to tolerate in the name of the greater success. That it would have been wiser to begin with the greater objective in mind may be true, but it is no justification for ignoring the decisions of political authorities. It is here we see the direct contradiction of “right to be wrong” civilians authorities ought to possess.3 In fear of civilians creating complications by revising their aims higher, Moltke advocates for a usurpation of their right to define the extent of the campaign. Thus, whether the aim of the war is the conquest of a portion of the enemy’s frontier or the utter overthrow of his government, Moltke’s position is that this should have no impact on the plan of campaign.

That the objective Moltke prescribed was, in fact, a logical illusion (to use a term of Clausewitz’s), and that this objective remained the orthodoxy of the General Staff, means that our first definition of victory is unworkable. The remaining options could both be fashioned into political purposes, but this would be a post hoc endeavor. Nevertheless, for the sake of our analysis of the merits of various war plans, we must determine a political purpose that we may judge them for succeeding or failing to obtain, as the Germans ought to have. The second definition is little help, as there was no firm understanding of what attaining Germany’s “place in the sun” constituted, whether this meant more colonies, more prestige, or outright hegemony over continental Europe. The idea of Germany’s objective strategic interest is only marginally less nebulous. Contemporary judgments of Germany’s strategic interests were colored by the prevalence of Social Darwinism, a worldview that could imagine only two outcomes: victory or civilizational annihilation.

If we wish not to get bogged down in a pedantic discussion of what victory would constitute, we could roughly set German ambitions as those laid out in the Septemberprogramm, though this was developed only after the start of the war. Of course, the nature of war as a political tool means that it is not necessary to achieve all of these goals for the result of a war to be considered a victory, as circumstances may make accepting less than complete success preferable to a continuation of the war.

What might be desired in war is naturally a separate question as to what costs are acceptable to attain them. Thus, the objective strategic situation must also be considered and the question asked whether the German position was as dire as its leading men believed. As mentioned earlier, the contemporary assessment of the strategic situation was greatly influenced by the school of Social Darwinism. There was therefore a form of fatalism among the German elite in the sense that it appeared to them that Germany faced a choice between war or a slow decline into dissolution. As difficult as it might be to believe, it was this phantasm that caused German decision-makers to accept far higher risks than they otherwise might have done. The axiomatic focus of the General Staff on total victory, born of parochialism and flawed theory, was overlooked in part because it was congruent with this vision of the future. We must therefore say, not only with the benefit of hindsight, but merely with an understanding of the weakness of social Darwinism as a theory, that the objective strategic situation was not dire for Germany.

For all the Germans complained about the encircling alliance as a “ring of steel” about them, it did nothing to arrest their commercial, industrial, and scientific rise. Nevertheless, that it faced an alliance of three great powers with only Austria-Hungary (and nominally Italy) for support was a less-than-ideal strategic situation for the German Empire. From this, we may derive that the minimum criteria for victory would be the dismantling of the Entente (which had been the objective of German diplomacy in previous crises). However, it does not follow that this objective is itself reason to desire a war, but would serve as a political purpose from which we could judge the success of war plans.

Three Concepts of Plans:

In pre-war German thinking, there were three notable concepts on which a war plan might be based, which are:

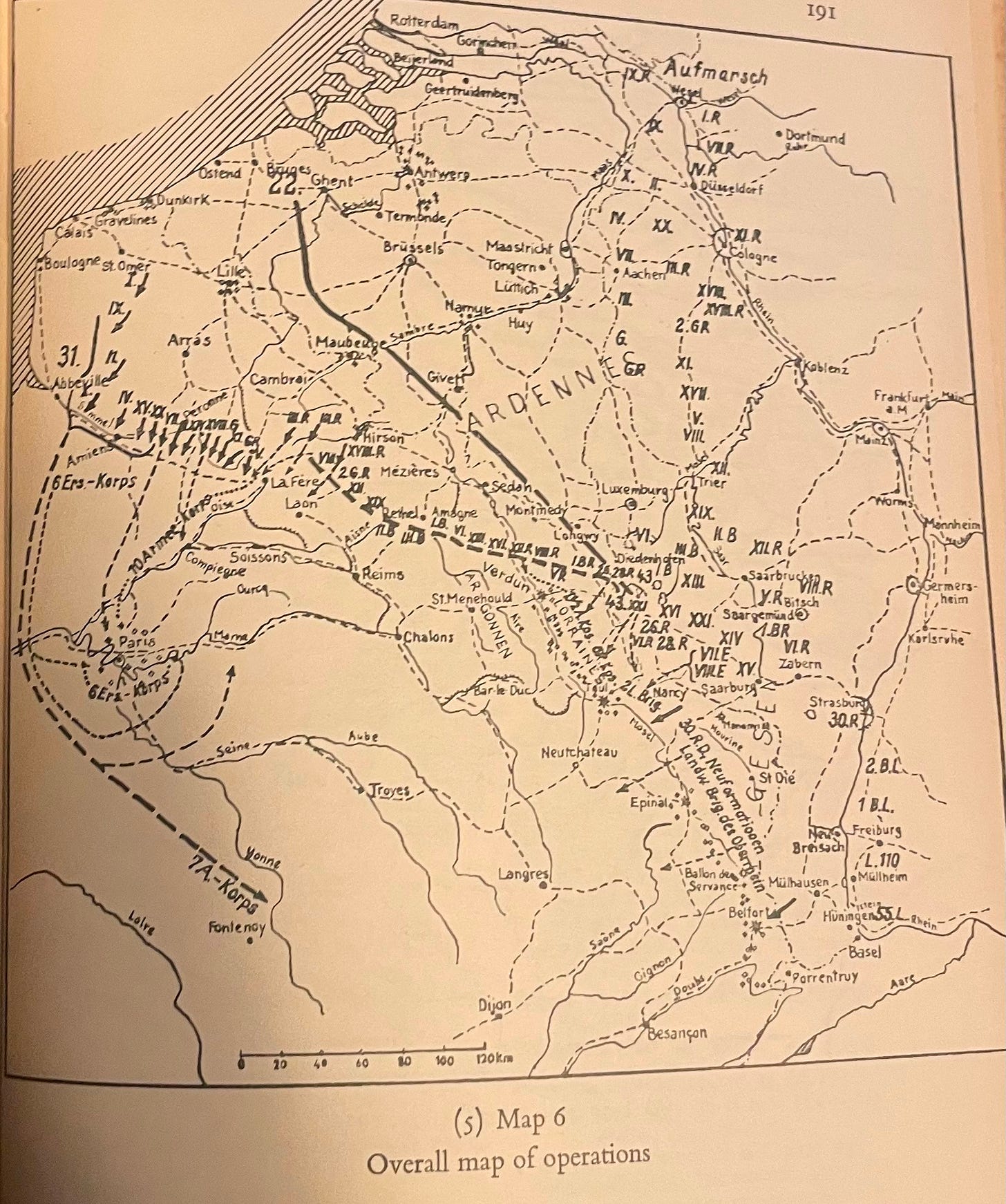

Through Belgium

This is the historical Schlieffen Plan, seeking to use the violation of Belgium neutrality to gain the room to maneuver and gain the flank of the French, thereby mitigating the effects of modern firepower. It presented the greatest chance at a “total victory” in the sense that if it succeeded, the French army would be defeated in series, and then encircled against the border. This would prevent the density of forces on the Western Front from creating a stalemate and then allow the victorious army to then strike east. The downside of this concept is that success relies on going through Belgium (and the Netherlands, in Schlieffen’s original concept) to reach the French left wing, which is an extreme feat of maneuver for an army that must literally march the distance. As such, this plan must be judged to be unlikely to succeed, as it requires a superhuman feat from the German right wing to be followed by an extreme margin of victory over the French, such that these exhausted men are capable of encircling them.

There are also a number of direct flaws with this plan. It severely limits diplomatic room to resolve a crisis, which is not true for other options. Further, the violation of Belgian sovereignty not only brings that nation into opposition, but provides political and emotional impetus for British involvement, as its government might otherwise struggle to make good on its commitments to the Entente. The extreme concentration on the right wing is naturally vulnerable to encirclement should the French successfully counterattack. The same concentration could also only be achieved by severely weakening Germany’s defenses in the East, which came with a serious risk that the Russians might well advance to Berlin before the French were defeated. Further, the attempt to completely defeat the French would naturally have a reciprocal effect in intensifying the emotions involved in the struggle. Particularly, if (as actually occurred) there is no justification for invading France in the reason for war, the pursuit of total victory will feed the perception that Germany is acting irresponsibly and unpredictably and so make a negotiated peace harder to obtain. The price of this erratic behavior is something addressed in a previous post.

Counterattack in Lorraine

The French were obliged to attack given their separation from the Russians and the vulnerability of Russia to a combined Central Powers offensive if the French remained on the defensive. This gave the Germans an opportunity to attempt to encircle the French attack by attacking its flanks and achieve a grand encirclement in Lorraine, a kind of “defensive Schlieffen Plan.” Schlieffen is considered this idea in his war games, though he came to doubt that the French would actually attack. Ironically, this approach would be a much more direct parallel to Schlieffen’s idyllic battle of Cannae, promising a double envelopment compared to the mere “super Leuthen” flank attack of the actual Schlieffen Plan. It also offers the chance at a total victory if the French are annihilated by the counterattack. But the destruction of the French is unlikely to be complete due to the difficulty in maneuvering in such a small area with such great masses of troops. The most likely outcome is a kind of ordinary victory in the West, and the consequences of failure or less-than-satisfactory success are by no means as dire as the Schlieffen Plan, as it does not require the same concentration or marching vast distances.

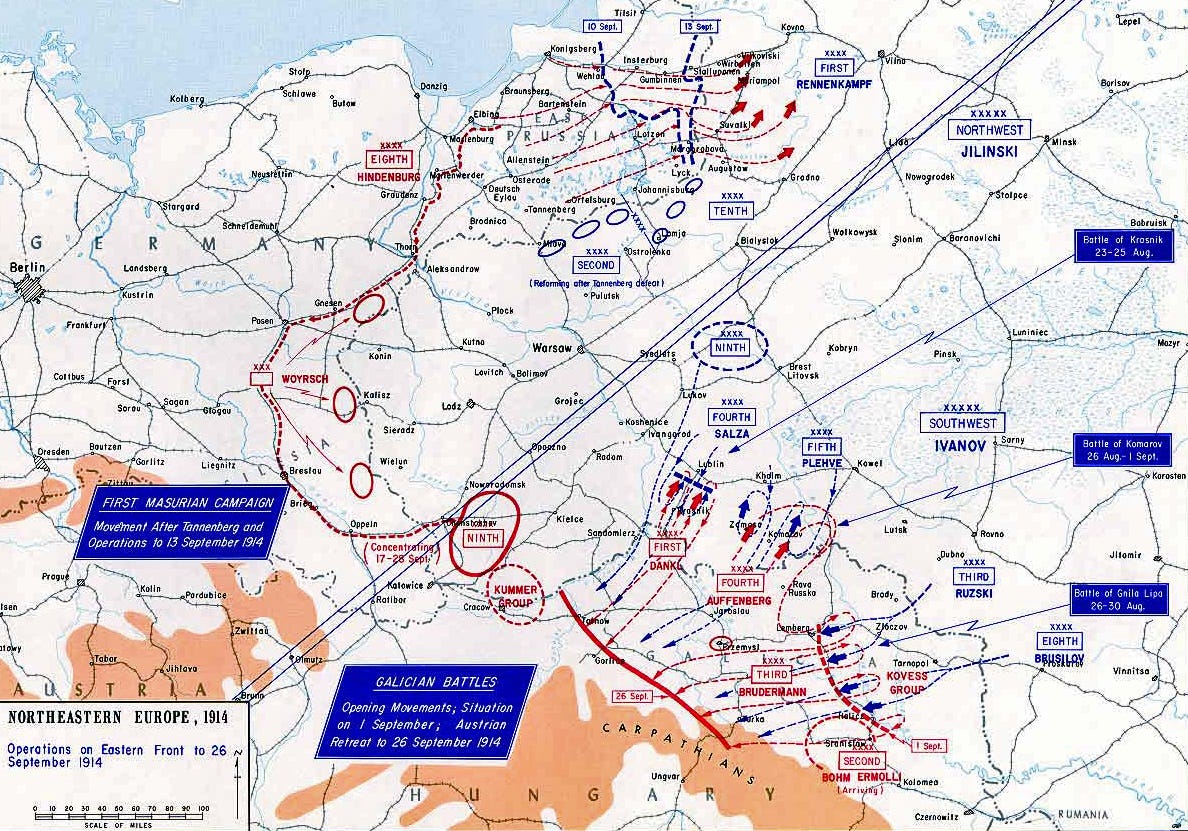

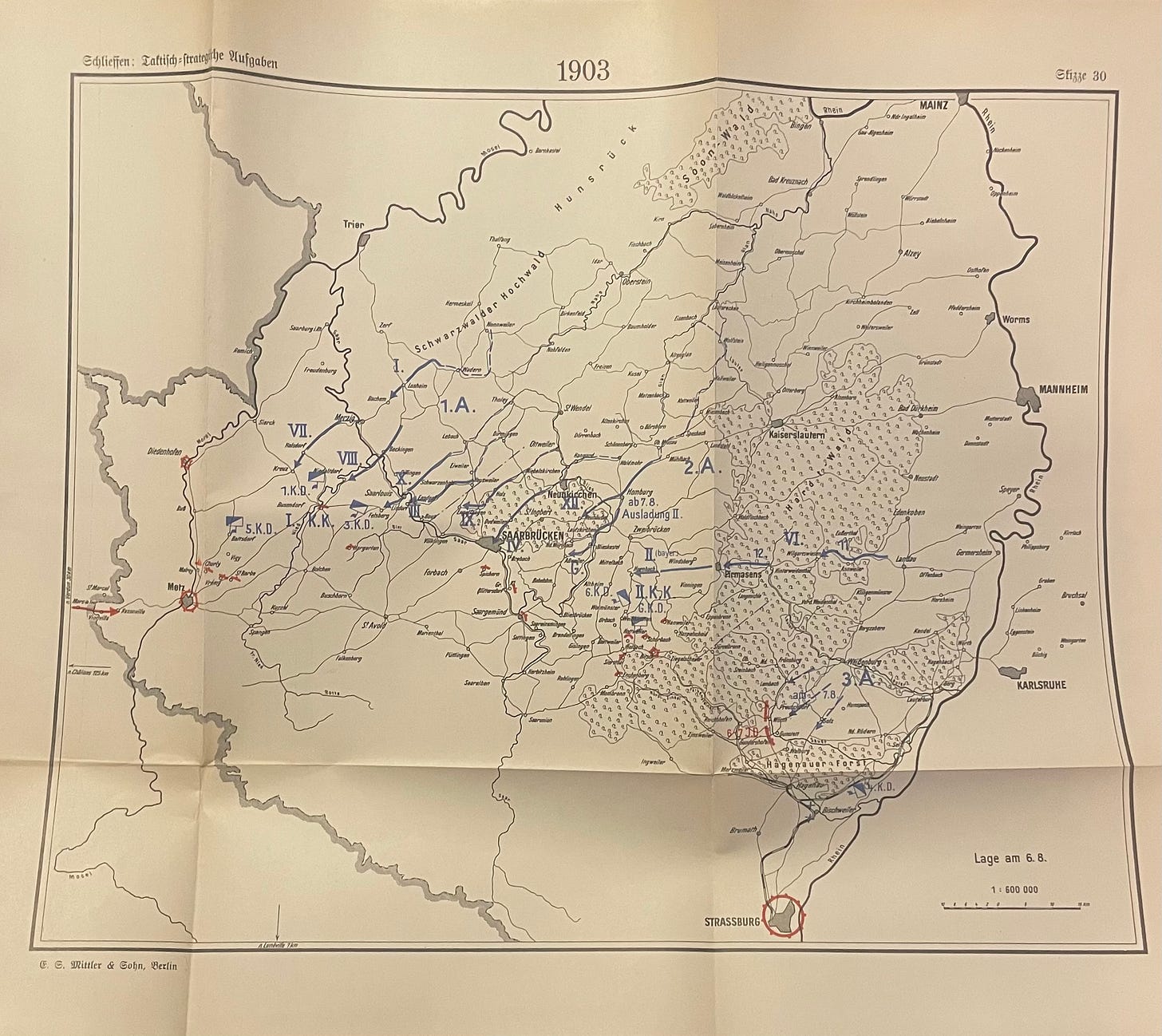

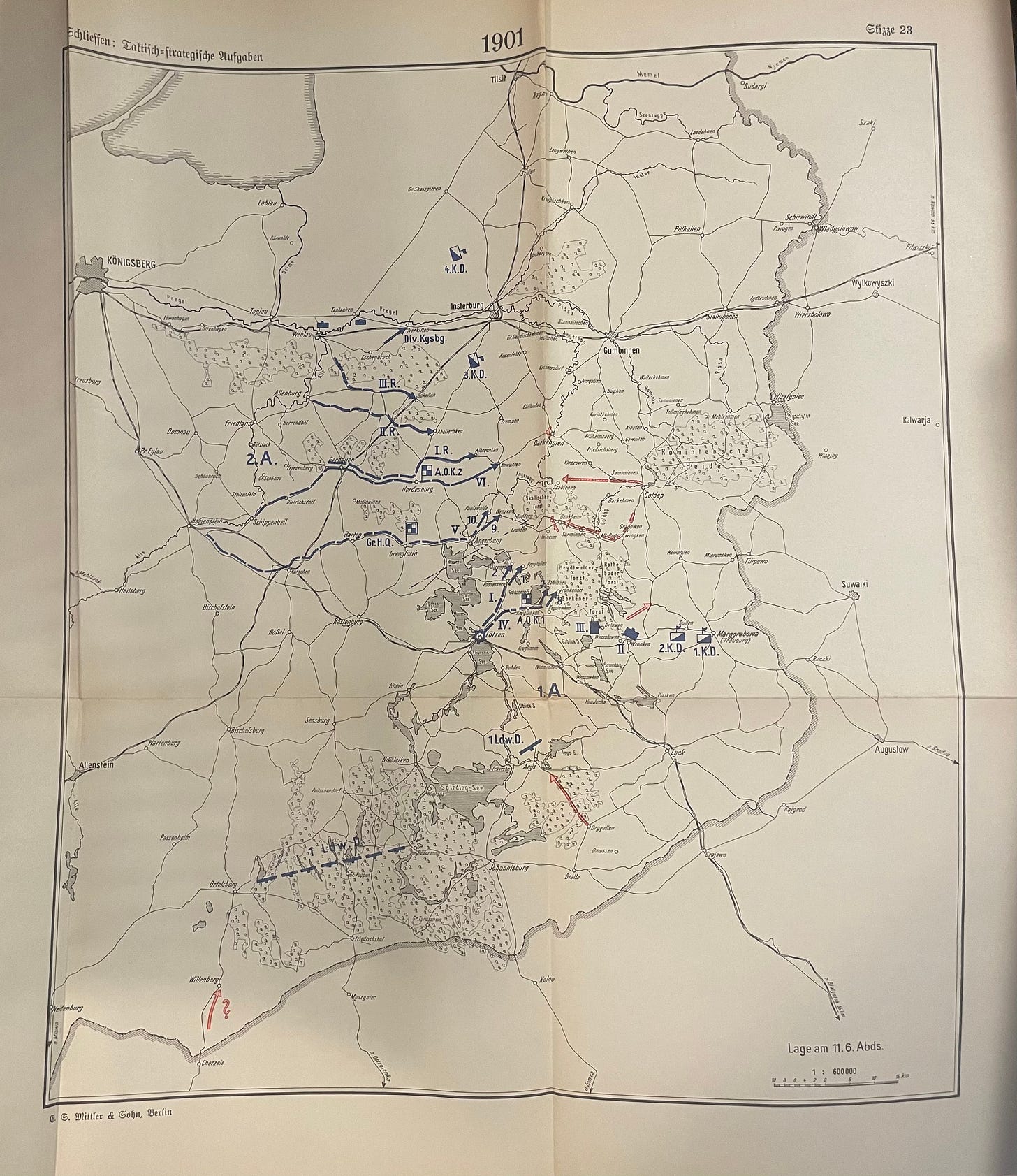

Strike East

Alternatively, the Germans could stand firm in the west and conduct a methodical campaign to force the Russians out of the war. This option was considered in numerous war games and maintained as a deployment plan (Aufmarsch Ost) until 1913. This approach would likely preclude an absolute victory as it would entail forgoing attempting to annihilate the French and instead aim for a favorable negotiated settlement. This aim is more limited, but also more likely to be successful (after WWI, German military historian Hans Delbrück would argue that this was the wiser plan). The example of the Russo-Japanese war demonstrated the vulnerability of the Tsarist regime to domestic unrest provoked by military defeat. Even if no did not occur, the Central Powers would still have a sufficient superiority in force to methodically overwhelm the Russians while holding the narrow Franco-German border.

These latter alternatives have the advantages of: not limiting the window for negotiations in a crisis, not violating the neutrality of Belgium, not relying on superhuman feats of marching, not leaving one front dangerously undermanned, not becoming obsolete as the Russians modernized, and not preventing the possibility of a limited war.

The Case for Aufmarsch Ost

The Schlieffen Plan aimed to destroy the French army and so allow a reallocation of forces to subsequently destroy the Russian army; it aimed at total victory, the highest reward. Relative to the Schlieffen Plan, a focus on Russia would be a lower-risk and lower-reward option. An attack east would mean conceding the chance for a total victory against the French, as this hinged upon leveraging Germany’s faster mobilization. However, Aufmarsch Ost had three factors in its favor over the Schlieffen Plan:

1. The overall inferior condition of the Russian army to the French

2. The room for maneuver that decreased the chances of stalemate

3. Suitability for encirclement

The first point speaks for itself. The second relates to the fact that while the expanse of Russia made a knock-out blow impossible, it also made a stalemate far less likely as, unlike in the West, firepower could not be strongly concentrated along the front, nor could reinforcements be swiftly moved from one area to another. For the third point, a brief glance at the territory of the Central Powers in the east shows Russian Poland to be a salient, encompassed by East Prussia in the North and Austrian Galicia to the South. As such, even should the Austrians fail to do more than hold their positions, a German offensive would be able to gain the flank of Russian forces in Poland, offering relatively easy access to the opportunity for annihilating them. Contrast this with the Schlieffen Plan, which required penetrating Belgium and nearing or encircling Paris before beginning its march back towards the border in its encircling movement.

The Eastern Front had more difficult topography and worse infrastructure, but, as Clausewitz tells us, war is not the action of a living force upon a dead mass, and so the superior infrastructure of the Western Front may have made it easier to employ great masses of forces, but this was true for both sides. Superiority in training and leadership could more easily make themselves felt in the difficult terrain of the East, whereas in the West (with a much smaller superiority in these factors) it was much easier to ensure a frontal confrontation of mass against mass that limited the effects of these advantages.

As Secretary of Defense Rock wrote in his piece on the topic,

“The plan would also have hinged on strong cooperation with Austria-Hungary, which in 1914, was practically nonexistent.”

Yet, it is crucial to note that the lack of cooperation between the Central Powers was limited primarily because the Germans did not want to tell their ally exactly how few forces it planned to leave in the east. The Younger Moltke had begun correspondence with his Austrian counterpart, but had been unwilling to engage in real joint planning specifically because of anticipated objections to leaving the Austro-Hungarians to face the Russians essentially alone until France was defeated.4 This, naturally, would not be a problem in the event that Germany was intending to open the war with an offensive to the east, and so deeper planning would therefore have been possible. Had the German General Staff been more inclined to view the strategic situation with the inclusion of its political aspects, it may have appreciated the value of Aufmarsch Ost in strengthening their own alliance while weakening that of the Entente.

The Schlieffen Plan must therefore be seen as the more riskier of the two options, being justified by its potential for knocking out France as well as Russia. It was premised on soundly defeating a force similar in quality, rather than a starkly inferior one; maneuvering through a short, fortified and densely manned front, rather than a sparsely defended one; and requiring a deep penetration and doubling back through hostile territory for encirclement, rather than taking advantage of a natural salient and an ally in the theater. While attacking east would have been less risky, the General Staff preferred an attack west for the reason that it could offer total victory.

The Contingency of History

The civil-military relations of the German empire prevented the axiomatic focus on total victory from being questioned. It was this, more than any systemic factors, that produced the European conflagration. A war over influence in the Balkans, even between the alliance blocs, might not have gone to extremes. However, a German offensive at Paris ensured that it could do nothing else. The high risk-high reward approach closed off the possibility of a negotiated settlement that an extended crisis might have brought. While Russia may have been willing to risk war over Serbia, France and Britain had no great interest in the country’s fate. Pressure from the Western powers against the Russians may have brought a resolution favorable to Austria-Hungary and Germany without war. Alternatively, given time, a compromise might have emerged that, while unfavorable to German interests, was nevertheless considered preferable to war.

The isolation of the General Staff meant that responsible political authority could not make the decision as to how long to give to negotiations, to weigh the benefits of avoiding war against the benefits of greater odds of victory. Likewise, there was no competent authority to weigh the odds of victory against the magnitude of victory sought. A political decision had been made in selecting a war plan aimed at total victory, one that could not be examined because it was emphatically declared to be apolitical.

Lest we conclude that this was the inevitable product of the structure of the German Empire, it must be remembered that, at any time, the Kaiser could have instituted any number of measures to ensure coordination between the army and the other apparatus of government. The Chief of the General Staff could also have, perhaps by reading Clausewitz more closely, understood the need for war plans to have a clear understanding of the political purpose behind them, and initiated cooperation with the Chancellor. Likewise, any Chancellor might have attempted to institute some kind of genuine strategic planning. However, it was not a coincidence that these things did not occur. The prestige of the General Staff made “intrusion” on its business difficult. Perhaps more significantly, Wilhelm II’s personalist system ensured that the men in the positions of highest responsibility were there because of favor, favor which could be lost if one seemed too ambitious.

There is, therefore, a clear explanation as to why decisions were made (or just as importantly, not made) that ensured the Schlieffen Plan retained its primacy, even as there was the continual opportunity to choose an alternative course. The shape of the conflict that erupted in 1914 was determined by choices which, influenced as they were by structural forces, nevertheless could have been radically different, and so produced a radically different situation. The grim vision of the future promised by Social Darwinism proved a self-fulfilling prophecy. One cannot help but recall Bismarck’s assessment of preventative war as “suicide for fear of death.” Had Imperial Germany found a means to subordinate its war planning to the conventional principles of statecraft (such as merely accepting the plain meaning of Clausewitz’s writings) it is unlikely to have produced the European conflagration that ultimately destroyed it.

The “Schlieffen Plan” refers to the overall concept of a massive attack through Belgium to gain the flank of the French army and annihilate it, rather than one specific war plan.

See Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, On Strategy (1871).

Peter Feaver in, Armed Servants: Agency, Oversight, and Civil-Military Relations (2003), coined the phrase.

See Annika Mombauer, Helmuth von Moltke and the Origins of the First World War, 114, citing correspondence between Moltke and Chief of the Austro-Hungarian General Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf.

Unaddressed remains the 'home by Christmas' mantra popular in all quarters at the onset of war. Choosing an Eastern plan would put paid to any such notion on the German part. Realistic planners would have quickly realized that any such war would be a lengthy one, considering the victory conditions against Russia would entail pursuit at least to the edges of Poland. Considering the past history of attacks on Russia, one could not reasonably expect terms at that point. In the event it required over three years of war to get Russia to the point of collapse and surrender. Selling that in preference to the potential Schlieffen rewards would have been difficult. I've had to brief out some very poor courses of action, and I can't see the long war being selected over the Schlieffen one.

Excellent presentation, as I noted unaddressed questions point by point I soon found you addressing them! Bravo. As noted, the Schlieffen plan placed enormous demands on the German infantry in particular. And as the General Staff kept hedging their bets they needed more formations some of which were filled by calling up reservists to make up the numbers. However, not all of these formations were given time for the training necessary to make them current on the latest doctrine and tactics. British and French officers in the west noted some of these units in the attack still using the Prussian tactics of 1870. Your reference to sunk costs is also on the mark as the war progressed as every nation adjusted their victory demands to reflect the sunk costs instead of the anticipated increased cost generated by the new objectives.