Beyond Maps and Frontlines: Analyzing Ukraine's Counteroffensive Progress

Why this stage of the counter-offensive shouldn't be measured in kilometers

“You hit someone with your fist, not with your fingers spread.” - Heinz Guderian

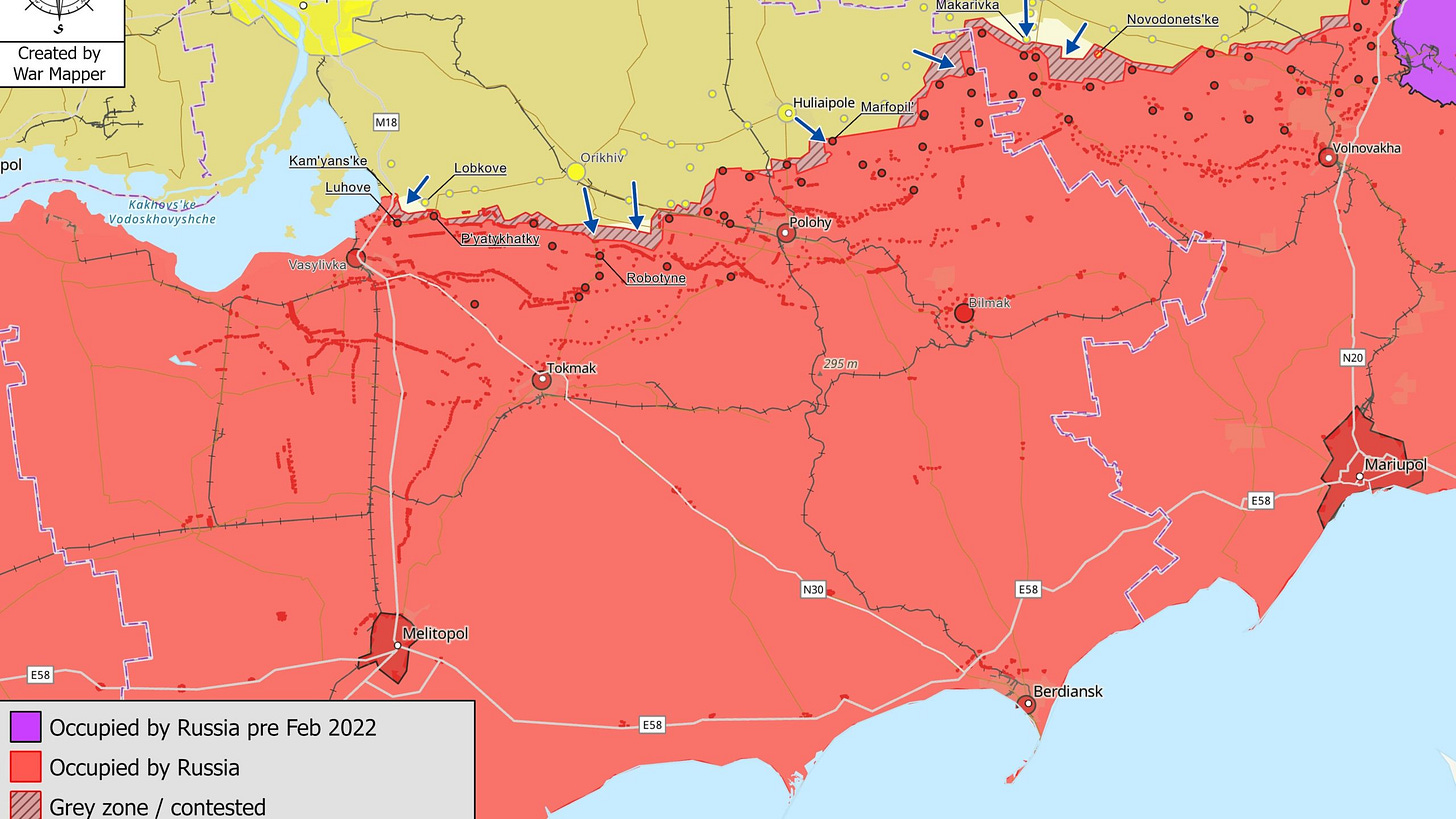

Ukraine’s counteroffensive began on June 6th. Weeks have passed, and maps of territorial control look much the same. It would have been ideal for Ukraine’s initial push to have shattered the Russian line and created the opportunity to rapidly liberate vast swathes of territory. Yet, in my opinion, it is too soon to despair for the success of the counteroffensive. Geography does not tell the whole story and, what’s more, it is still too early to judge the success of operations thus far. In this article, I will argue that Ukraine’s efforts are congruent with the operational concept of a fixing attack and use the Battle of France to demonstrate how fixing attacks can be used to achieve decisive results.

At present, it is not possible to assess Ukraine’s operational intentions. This is, of course, by design. Ukraine’s opening attacks do not commit it to a particular approach, which places Russia in a position of uncertainty. If Ukraine intends to gradually advance until it can target Russian supply lines to occupied southern Ukraine, Russia ought to make every effort to avoid such an outcome. However, if Ukraine’s attack is a fixing effort, Russia would be playing into their hands by committing its reserves. Yet, failing to commit reserves for fear of a breakthrough can lead to the current axis of advance attaining its objectives. Thus, Ukraine’s secrecy surrounding the operational concept that underpins its offensive presents Russia with a dilemma, where attempting to forestall one approach enables another.

At the moment, Ukraine is engaging Russia along a broad front. The primary purpose of this is both to fix Russian forces into defending their positions, preventing units from being redeployed towards more critical sectors. In these operations, the goal is not so much to actually break through the Russian lines but to threaten it. The objective is to present the Russians with as many potential points of crisis as possible so as to both tempt and force the commitment of reserves.

The more Russia commits its reserves to shoring up its defenses at disparate points along the line, the more vulnerable it becomes to the main breakthrough effort. Ukraine will seek to continue these operations until it believes it has tied down enough Russian forces that its breakthrough force cannot easily be contained.

Additionally, the continual threat of breakthroughs makes it more likely that Russia will fail to identify the actual point of concentration Russia has to question constantly which pressured axis is the decisive one. Ukraine therefore is forcing Russia into a dilemma in which it must either spread its reserves trying to contain every dangerous point-leaving itself vulnerable if the main effort comes at an unexpected point or it must wait to react to a report of a potential breakthrough until it is confirmed, delaying its response at a critical moment.

This breakthrough force is the decisive element as to whether the counter-offensive succeeds or fails. It is for this reason that reputable commentators have abstained from providing conclusions on the counter-offensive. Events thus far will affect the odds of the breakthrough force being successful, but short of a catastrophe on one side or the other will not prove decisive.

The basis on which I assess this without access to the operational plans of either side or intelligence regarding their intentions is because this concept of operations has persisted since the Second World War. If one wishes to truly be a historical essentialist, the concept can be viewed as a scaled-up version of the “hammer and anvil” tactics of Alexander the Great.

As general and tank theorist Heinz Guderian famously said, “You hit someone with your fist, not with your finger spread.” Ukraine’s operations across a broad front seem in contradiction to this concept. Yet fixing operations are a vital element in enabling a breakthrough. In fact, arguably the most auspicious victory of Guderian’s career-the Battle of France-utilized an approach that parallel’s Ukraine’s efforts. For sake of comparison, I will provide a brief overview.

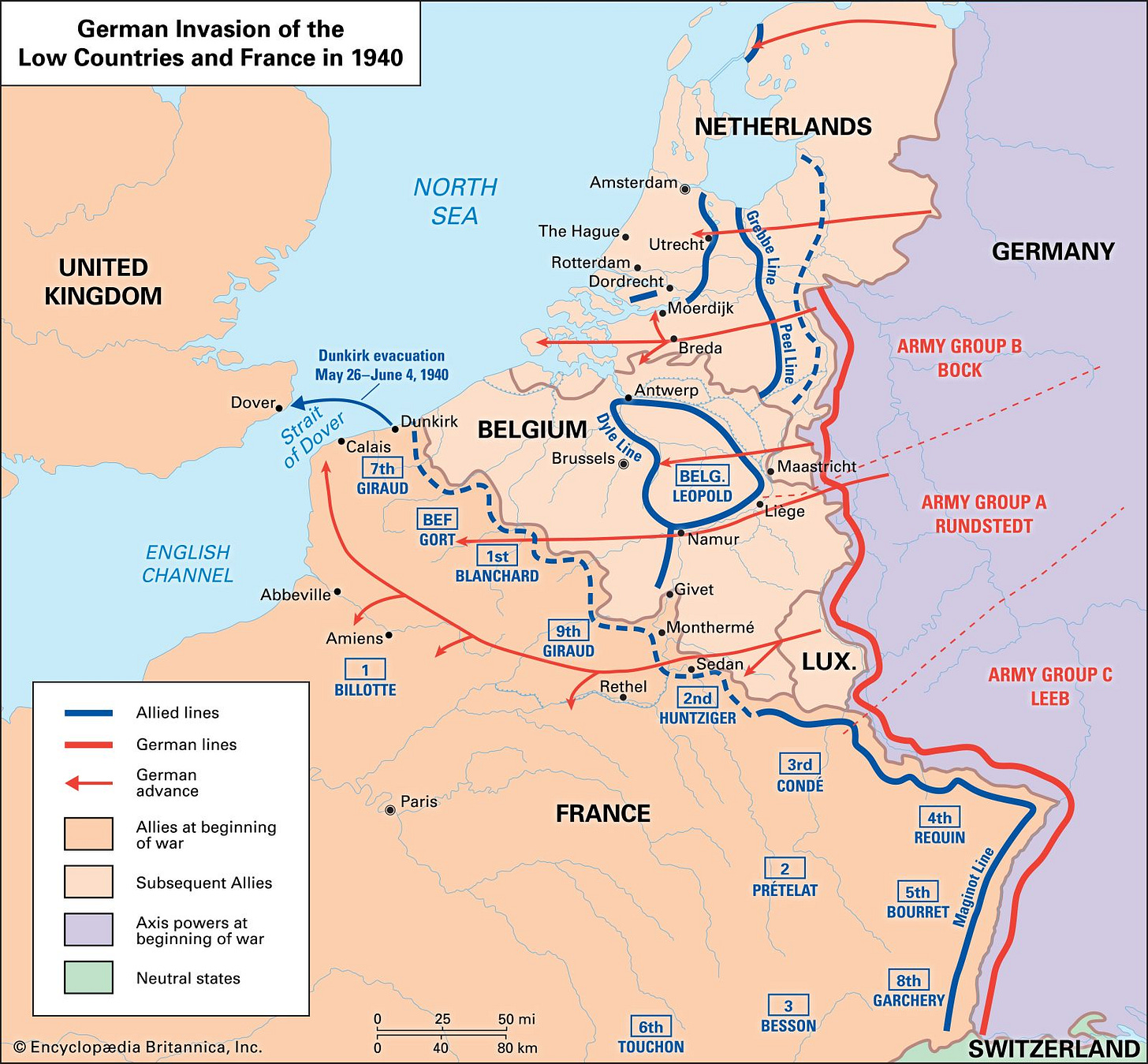

The German land forces were divided into three Army Groups. Army Group B, in the north, opposing Allied forces in the Netherlands and Belgium, Army Group A, concentrated against Luxemburg, and Army Group C, which opposed France’s fortified Maginot Line. Army Group C’s purpose was primarily to force France to man the fortresses along the border and so saw little action.

Army Group B and Army Group A’s missions are most useful for understanding the use of fixing operations to allow a breakthrough. Army Group B attacked into the Low Countries, wheeling against the coast, almost in imitation of Germany’s approach in 1914. This was an assault in earnest and made significant progress. It needed to in order to be effective. Its goal was to commit as much of the Allied army as possible to resisting its advance. The Allied strategy anticipated a push from the German right wing and moved considerable forces to blunt it, intending to bog it down in the kind of stalemate that had led to German defeat in WWI as Allied advantages in seapower and industry became decisive.

It was clear to the Germans what the Allies intended. It was also clear Germany could not win a long war, and therefore a decision was made on the political level to utilize a risky plan of operations. Army Group B was tasked with the decisive breakthrough on which the war was likely to hinge. To this end, it was provided with nearly all of Germany’s armored and motorized formations. It was in this force that Guderian served, at the head of the XIX army corps, under overall commander of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt.

The operation proved more successful than the Germans had dreamed-the Allies, meeting initial success in halting what they thought to be the main German effort, surged in to secure the Low Countries. Army Group A broke through at a point far south of the main Allied concentration and sent its mobile divisions rushing to the Channel. Within twenty-four hours, the Allied forces in the Low Countries were encircled and cut off from France and resupply. In the aftermath, France collapsed with the British Expeditionary Force avoiding capture through the famous evacuation at Dunkirk.

The Battle of France illustrates a number of key principles of modern operations. Most relevant for our analysis is that large masses of forces cannot quickly reorient.

The attack in the north by Army Group B was a feint-but it was also an attack in earnest. It made rapid progress through Belgium and the Netherlands, and the force of it was enough to convince the Allies it was the main effort. With the Allies committed to defending the Low Countries, when Army Group A broke through in an unexpected point, its tank and motorized divisions cut off the Allied forces. Army Group A’s tank and motorized divisions were drastically inferior in numbers to the Allied forces they were encircling, but the Allies were unable to turn and break out of the encirclement. Under pressure from Army Group B, and cut off by Army Group A, Allied forces were forced to surrender.

To put it lightly, the case of the German victory in 1940 is exceptional. The confluence of factors that enabled such a resounding victory are rare in war. However, the exaggerated nature of the success makes the case useful for illustrating the operational concepts used. The success of Army Group B in fixing Allied Forces and inducing the commitment of reserves was essential to the breakthrough of Army Group A. Ukraine’s attacks on the southerly axis in the direction of Zaporizhzhia are clearly most similar to Army Group B. As a result, this effort can be used to create the conditions for a breakthrough comparable in means, if not in scale, to that of Army Group A.

A methodical advance across a relatively broad front such as Ukraine is using is not inconsistent with mobile operations and is-in fact-ordinarily a prerequisite. If Ukraine is intending primarily to fix Russian forces to enable a breakthrough elsewhere, it would be a mistake to judge the progress of the offensive based on the ground gained. The forward progress of Ukraine’s counteroffensive is only directly relevant if Ukraine intends to force withdrawal by bringing Russian supply lines within artillery range.

This is not to say Ukraine is necessarily following the operational concept of utilizing a fixing force to enable the success of a breakthrough force. As I have argued in the past, Ukraine must choose between attempting the kind of deep penetrations the Germans achieved in 1940 (and Ukraine itself achieved at Kharkiv) and conducting an advance that is merely sufficient to make the Russian occupation in the south (potentially including Crimea) unsustainable. Ukraine’s operations so far are consistent with both approaches.

None of this is to say the battlefield success of the pinning force is irrelevant. In fact, a fixing effort can only be successful if it threatens a disaster if unaddressed. This quality is measured by the commitment of Russian reserves, not in kilometers. The operational disposition of Russian forces in Ukraine is obviously not publicly available information, and so the degree of success of a fixing operation is inevitably unclear.

It is therefore crucial to resist the impulse to look too closely at the progress of the offensive. Analysis based on reported loss numbers, geolocated combat footage, and claimed advances will tell only the smallest part of the story. The success of this stage of the counteroffensive is to be judged on whether it ultimately either enables a breakthrough elsewhere by tying up reserves or brings Russian supply lines into striking range.