Clausewitz On Activism: Professionalism and Parochialism

What Progressive Activists, the German General Staff, and Battlefield Earth all have in common

Recently, I read Jeremiah Johnson’s piece, “Activism is Not a Social Club.” While doing so I came notice that Carl von Clausewitz’s On War offers a useful framework for understanding effective activism. This may not be surprising to those familiar with the basic premise of his work, but there is a sordid history of contorting famous works on the subject of war to fit all areas of life. Ordinarily, this is only possible through mutilating the author’s intent and turning the text into a Rorschach test for the interpreter. As a result, a bit of justification is necessary.

Fortunately for modern readers, Peter Paret and Michael Howard suitably contextualize their modern translation of On War, whereas Wernher Halweg’s commentary on the German edition has done much to reveal myths born of misinterpretation and motivated reasoning. Armed with an understanding of Clausewitz’s intentions and meanings from the works of these eminent scholars, we may avoid some of the pitfalls that plagued earlier interpreters.

The topic of activism is, perhaps counter-intuitively, a relatively safe place to begin broadening our application of Clausewitz. Clausewitz wrote that “war has a grammar of its own, but not its own logic.” As he argues, the logic of war is borrowed from politics. Therefore Clausewitz’s discussions on strategy have relevance to politics whether or not violence is in the mixture. The logic remains the same even as the form changes. While Clausewitz was concerned with demonstrating how this applied to war specifically, his discussions of the strategic-political level of war bring an uncommon clarity in outlining the logic of politics.

“If the enemy is to be coerced you must put him in a situation that is even more unpleasant than the sacrifice you call on him to make.”

-Carl von Clausewitz, “On War”

In both war and activism, the fundamental objective is persuasion. When violence is added to the mix the term “coercion” may be more fitting, but the key point is that an agreement—even at gunpoint—is an agreement. The acceptance of both parties is necessary. As a result, the aim in all cases is to persuade your opponent that agreeing to your demands is preferable to continuing the struggle. This is true even if you have the means to seize something by sheer force. After all, taking something is one thing, but keeping it is another. If your opponent does not agree, whether tacitly or explicitly, to accept the loss, the struggle continues.

“The hardships of that situation must not of course be merely transient-at least not in appearance. Otherwise the enemy would not give in but would wait for things to improve. Any change that might be brought about by continuing hostilities must then, at least in theory, be of a kind to bring the enemy still greater disadvantages.”

Both the activist and soldier are faced with the task of inflicting a situation on their opposition that makes agreement the path of least resistance. The question of how to accomplish this brings us to the concepts of tactics and strategy respectively.

Tactics-Means

Tactics are the ways by which battles—whether literal or metaphor—are won. Battles are not fought for their own sake, but because victory provides leverage to achieve something. The tactical level can be seen as the technical work of acquiring the “capital” needed to attain the political objective. This is the linkage between the tactical and the strategic.

The tactical level is most properly the realm of the specialist. The soldier or activist both have specific technical knowledge that is required to fulfill their functions. From this, as Samuel Huntington argued in The Soldier and the State, comes the status of a profession. Professionals form a group or class, made exclusive by the particular knowledge or skills that separate them from laymen. However, with professionalism comes the danger of parochialism. Experts will always be tempted to focus on their areas of authority and resent any perceived intrusion from the uninitiated.

Strategy-Ends

“The original means of strategy is victory—that is, tactical success; its ends . . . are those objects which will lead directly to peace.”

Strategy, in Clausewitzian terms, is determining which immediate objectives will lead to a victorious peace. While tactics is the process of actually acquiring them, strategy is determining what should be acquired. It is the process of judging the relative importance of objectives as well as developing a framework that connects the subsidiary objects with the ultimate goal sought. “Victory” is defined as achieving whatever your political aims are. This is the heart of Clausewitz’s understanding of the nature of war, that it is merely the pursuit of political objects with the additional means of violent action.

Strategy means answering two difficult questions: 1. Under what conditions will your opponent accede to your demands? How can these conditions be achieved with the means available to you?

It is these determinations that will inform and limit the choices of tactics available to you. Certain means are incompatible with certain ends. The question of “what conditions” is the social aspect and one of Clausewitz’s main contributions to the study of war. War is an interaction between two groups of people and is therefore a social activity, not only within the warring societies, but between them. A strategy for victory means making a judgment of what conditions it will take to convince your enemy that giving you what you want is preferable to continuing the struggle. As Clausewitz writes, “The same political object can elicit differing reactions from different peoples, and even from the same people at different times.” This sentence needs no alteration to be relevant in the context of activism.

A Historical Lesson

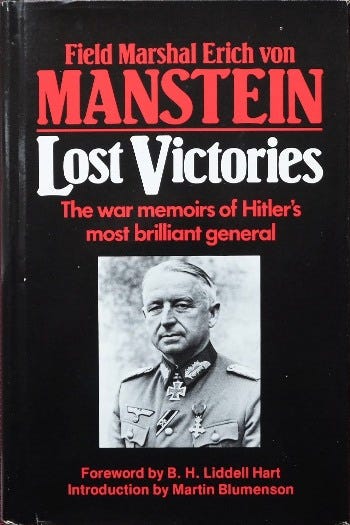

Unexpectedly, when looking at modern progressive activism, it appears to have fallen into the same intellectual trap of the German General Staff in both World Wars in that an overemphasis on the tactical level has led to a neglect of the strategic. What they have in common is a faith that fighting battles in isolation well enough will lead to victory. In war, military professionals tend to have an attraction to the parts of war exclusive to it, as they represent the soul of the “profession.” Through this attraction, there is a danger for the specialist (the activist as well as the soldier) to hyper-specialize. The German General Staff blinkered itself by focusing on the tactical and operational problems that remained within its authority and specialty and failed to coordinate with political leadership to develop a cohesive strategy. Thus, after the wars, it bemoaned its “lost victories” (as Erich von Manstein titled his memoirs) yet failed to consider its own role in failing to develop a strategy to use those tactical successes to achieve a victorious peace. Equally, activists often focus on metrics such engagement and disruption while failing to coordinate with campaigns and politicians. The end result is an absurd situation where tactical success—the means—becomes an end in itself and the difficult work of strategy is abandoned.

Some notable recent cases illustrate the point when it comes to activism.

Of course, there is the viral incident of the Bakersfield city council, in which a woman has found herself imprisoned for making all-kinds of threats because of a refusal by the local government to take a stand on Israel-Palestine. This is only the deranged tip of an absurd iceberg. Countless local governments and student organizations have decided to weigh in on the matter, with activists celebrating these and condemning those that fail to do so. They, who argue that a genocide is in progress in Gaza, believe statements of condemnation from organizations with precisely zero international relevance are an appropriate means of redress. One must wonder which interpretation is more charitable towards them: that they are using the term “genocide” carelessly and dishonestly or that they really believe votes by town councils will stop the murder of a population? There is a clear lack of consideration of the suitability of means and ends.

Another example is the act of blocking traffic. What purpose does obstructing random passers-by serve? To this, activists may answer that it spreads awareness or that disruption is itself a means of pressure. Or, less credibly, it may be used in an attempt to demonstrate perceived hypocrisy, that the public cares more about the disruption than other, larger issues (such as climate change). What these all lack is an answer as to how the immediate goal contributes to achieving the larger objective. You can make people aware of your cause, but that doesn’t mean they’ll agree, much less to prioritize it above all else. The average commuter made late for work by a protest is unlikely to become more sympathetic to the cause of the protestors. You can, of course, try to pressure people through your disruption by promising to let up only if your demands are met. But pressure is only effective if enough can be applied in a way that giving in is preferable to all alternatives. This is extremely difficult through the means of disruptive protesting. After all, in almost all cases it is simpler to remove the disruption than it is to agree to the demands of the disruptors.

A Less Historical Example

In Roger Ebert’s famous review of the cinematic disaster, Battlefield Earth, he writes of the incessant “Dutch-angles” that: “The director, Roger Christian, has learned from better films that directors sometimes tilt their cameras, but he has not learned why.” In the same vein, I would suggest that many activists have learned from better-organized social-movements that protestors sometimes take disruptive action, but they have not learned why.

The end product of both is the most superficial imitation possible, seeking to replicate the appearance of the original without any consideration of its meaning and purpose. It is action without strategy. The activist who organizes protests without a clear-eyed view as to how they contribute to bringing about the changes they desire is as useless as the officer who seeks a battle without asking how it contributes to bringing about the policy goals of their government. Of course, the consequences of the officer’s error will be greater, but politics is serious business, even without violence added to the mix. A failed protest consumes as much political and organizing capital as a successful one. The desire to act and take the initiative is commendable. But it can be worse than useless if done thoughtlessly.

Acting strategically means clearly understanding why you are doing what you are doing. It means knowing exactly how what you are doing today will contribute to what you want to accomplish. If you’re going through the motions with a blind faith they will inexplicably produce results, that’s not a campaign, it’s a cargo cult.