Clausewitz on the Very Bad Ideas to Reform the War Colleges

An Opportunity to Expose Errors and Discuss How One Can Gain Experience From Books

Anyone who has read and understood even the smallest part of On War can identify the contradictions in the following assertions:

If America’s War Colleges teach politics instead of war, strategic failure is inevitable… [war college] curricula need to build warfighters who think strategically, not uniformed ‘strategists’ who are more concerned with diplomacy than closing with and destroying America’s enemies.

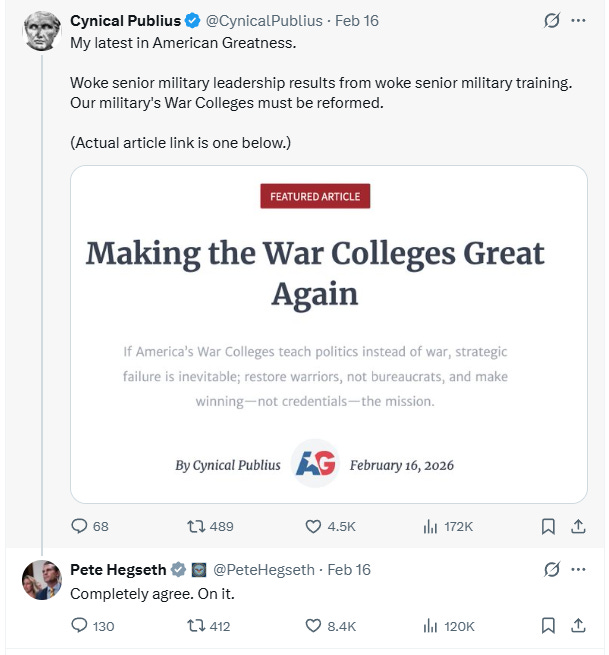

These come from the pictured article by a pseudonymous author, with the risible title “Making the War Colleges Great Again.” The author is apparently a retired officer who attended one of these institutions. Amongst his criticisms and suggestions, he calls for the purging of civilian faculty, at least partly on the basis of their “visceral and vocal hatred for the current administration.” This advocacy for Soviet-style “political correctness” from war college faculty is a view unfit for any American, let alone an officer, and gives you some idea of the tenor of the article.

The piece is banally shallow and incompetent, only worth reading in full if you have a sense of morbid curiosity. Nevertheless, we can still make use of it by following Clausewitz’s example of using the shoddy work of others to illustrate a better way to study war. Throughout this article, I will be juxtaposing arguments made in the essay with quotes from On War to elucidate Clausewitz’s concept of military education.

Theory then becomes a guide to anyone who wants to learn about war from books; it will light his way, ease his progress, train his judgment, and help him to avoid pitfalls… It is meant to educate the mind of the future commander, or, more accurately, to guide him in his self-education, not to accompany him to the battlefield; just as a wise teacher guides and stimulates a young man’s intellectual development, but is careful not to lead him by the hand for the rest of his life.

-Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Book II: 141.

The Aim of Education

In his book Decoding Clausewitz, Jon Tetsuro Sumida argues that Clausewitz had the major purpose in On War of establishing a method of developing military skill, or genius. He cites Clausewitz, “The knowledge needed by a senior commander is distinguished by the fact that it can only be attained by a special talent, through the medium of reflection, study and thought: an intellectual instinct which extracts the essence from the phenomena of life, as bee sucks honey from a flower.”1 By this, Clausewitz means the kind of intuition necessary to grasp the essence of a situation from the incomplete information available and within the general strain and chaos of war. Sumida argues that the method Clausewitz envisioned for developing this talent was the mental reenactment of command decision-making, using historical examples. He writes:

This combination of theory and history amounts to historical reenactment of strategic and tactical decision-making experience, which is to be followed by reflection on that experience. The two actions constitute a form of learning that approximates that which takes place in actual war of any kind… Clausewitz regards his theoretical approaches as scientific because their primary function is to make possible productive observation of particular experience… rather than to serve as guides to decision-making.2

Indeed, Clausewitz himself is explicit that developing a particular way of learning from experience is the only possible and therefore legitimate goal of theory. He writes,

A Positive Doctrine is Unattainable

Given the nature of our subject, we must remind ourselves that it is simply not possible to construct a model for that of war that can serve as a scaffolding on which the commander can rely for support at any time. Whenever he has to fall back on his innate talent, he will find himself outside the model and in conflict with it; no matter how versatile the code, the situation will always lead to the consequences we have alluded to: talent and genius operate outside the rules and theory conflicts with practice.3

Since positive doctrine is impossible, the role of theory is thus to stimulate the mind to develop talent and genius so that, in actual war when a commander must rely upon it, the muscle is well-trained, so to speak. No set of rules can capture all the possibilities of war and war itself involves circumstances that preclude the systematic, rational investigation of all possibilities. Clausewitz therefore declares: “Knowledge must be so absorbed into the mind that it almost ceases to exist in a separate, objective way.”4 He elaborates: “In almost any other art or profession a man can work with truths he has learned from musty books, but which have no life or meaning for him. Even truths that are in constant use and are always to hand may still be externals.” He gives the example of an architect applying a formula to determine the strength of a feature of a building, using a process that is set, “of whose logic he is not at the moment fully conscious, but which he applies for the most part mechanically. It is never like that in war. Continual change and the need to respond to it compels the commander to carry the whole intellectual apparatus of his knowledge within him… By total assimilation with his mind and life, the commander’s knowledge must be transformed into a genuine capability.”

From this it follows that the aim of education must be the development of a comprehensive capacity for intuitive judgment, so that an accurate assessment can be made without conscious reasoning, for which there is no time in war. Even in modern war where much more information is available to the commander, this hold true. The availability of information in no way alleviates the necessity for the kind of skill that Clausewitz describes; the commander must still discern the essential significance that lies behind all the information presented to them. They must do this in trying conditions, with information they know may be false, outdated, deceptive, or mischaracterized. They must therefore rely—not on rules or formulas—but their judgment and intuition, which can only be honed by experience.

The Method

Clausewitz posits that the only effective means of education for higher ranking officers is the critical analysis of military history, by which he means a detailed mental recreation of the decisions of the relevant commanders, guided but not subordinated to theory (which is in turn tested against the historical record). Through this process, which he terms “critical analysis,” a prospective commander may turn the dusty tomes he consults into a serviceable approximation of experience in higher command.

Clausewitz examines Napoleon’s decision to lift the siege of Mantua to attack the Austrian relief force.5 While he won a famous victory, he lost the siege train necessary to take the city, being forced to blockade it for another six months. Clausewitz argues that Napoleon might have instead taken the defensive with his 40,000 men against the relief force of 50,000 and instead actually taken the city by siege and that as doing so would have had a greater strategic effect than the destruction of the relief force. He views Napoleon’s decision as influenced by the at-the-time prevailing but superficial view that defending siege lines was an outdated form of fighting, typical of the 17th century. Clausewitz identifies this oversight as the likely cause of the decision, rather being developed through a serious consideration of the alternative, which appears to have never struck Napoleon.

Clausewitz argues that, through critical analysis, we can see that despite Napoleon’s bold intent in attacking the relief force it was—in reality—the lower risk, lower reward option compared to continuing the siege and daring the Austrians to try to relieve it. Napoleon’s bias towards offensive action and deference to conventional views on forms led him to do the opposite of what he really intended—he wanted to take the more audacious course that promised a greater victory, but in reality ended up on the safer road with a lesser magnitude of success.

It is this kind of analysis that can hone the capacity necessary for higher command: looking critically from the perspective of the commanders involved and asking: what did they know? What were they trying to do? What drove their decision? What alternatives did they have? What effects did this choice have? What effects would the alternatives have produced? This, in Clausewitz’s view, was the purpose of critical analysis: to allow future commanders to hone their judgment and synthesizing intellect through the study of military history and the empathetic consideration of the judgments of past commanders. As Clausewitz writes,

“What is most needed in the lower ranks is courage and self-sacrifice, but there are fewer problems to be solved by intelligence and judgment. The field of action is more limited, means and ends are fewer in number, and the data more concrete: usually they are limited to what is actually visible. But the higher the rank, the more the problems multiply, reaching their highest point in the supreme commander. At this level, almost all solutions must be left to imaginative intellect.6

Clausewitz’s intent was to create a theory that would enable the development of this imaginative intellect, so that officers could be prepared to face the myriad of unique situations that each particular war produced and for which no doctrine could account. It is the responsibilities of higher command, of making sense of a complex situation with incomplete information under duress, that require true genius and a cultivated insight. The role of education for senior officers such as attend the war colleges ought to be to provide students with these tools, not fixate on pedantic issues best reserved for field manuals.

Tactics And Strategy

We must staff War College faculty [sic] with our best warfighters, ones who have had a successful tactical command at the colonel/captain level...

No great commander was ever a man of limited intellect. But there are numerous cases of men who served with the greatest distinction in the lower ranks and turned out barely mediocre in the highest commands, because their intellectual powers were inadequate.7

The tactically successful can impart tactical wisdom and help refine the positive doctrines that are suitable for that level of war. Duties of higher command, which the war colleges ought to be concerned with, require starkly different capabilities than lower levels of leadership. Achieving tactical success is not easy, but it requires more physical courage than moral courage or a penetrating insight. A record of tactical success is no guarantee of strategic insight, as the history of war shows.

Tactical success therefore has little to offer to the development of the creative mind necessary for higher levels of command responsibility, where the currency is the synthesis and comprehension of how the glimpsed parts stand in relation to the whole. Clausewitz is very clear about why tactical instruction is an unsuitable focus for the education of senior officers:

…anyone who thought it necessary or even useful to begin the education of a future general with a knowledge of all the details has always been scoffed at as a ridiculous pedant. Indeed, that method can easily be proved to be harmful: for the mind is formed by the knowledge and the direction of ideas it receives and the guidance it is given. Great things alone make a great mind, and petty things will make a petty mind unless a man rejects them as completely alien.8

An overemphasis on the business of fighting and killing will lead officers to be concerned with things below their responsibility, and to view war as a matter of applying set formulas to given problems, as tactics can resemble. This kind of education would be suitable only for the mediocre, its lessons ringing false to anyone with a real genius for higher command. We can only pity the officer who imbibes purely these pedantic platitudes and must face an opponent whose thinking has been whetted by critical analysis of actual strategic problems.

The author also persists in the “lethality obsession” that I have previously written on, intoning: “[war colleges] are schools to teach senior leaders how to better kill the enemy.” The business of higher officers is not killing anyone directly. Clausewitz declares that, “In many cases, particularly those involving great and decisive actions, the analysis must extend to the ultimate objective, which is to bring about peace.”9 He then goes on to provide an example of analyzing Napoleon’s 1799 campaign in Italy, looking at Napoleon’s reasons for advancing on Vienna and connecting it with his decision to shortly after sign a relatively moderate peace with the Austrians as well as the Austrian decision to cede provinces to France rather than try to wage a more total war of resistance.

He traces the military circumstances (Napoleon had overextended himself, the Austrians had fewer forces available to defend Vienna than Napoleon believed they might) to the ultimate mutual political decision to accept peace. It is this process that Clausewitz argues provides the strategic experience that develops the intuition needed for higher leadership, and consists the method of “mental reenactment” Sumida argues is at the core of On War. As Clausewitz repeats, violence and killing are only part of combat, which is the means of war, while the ends are “those objects which lead directly to peace.” The latter is the aim of strategy, with which senior leadership is concerned and which gives significance to tactical success.

Self-Conception

The civilian suit madness sends a deep, deep subliminal signal that says, “You are no longer a warrior, You are now a politician, or a civil servant, or a contractor. Welcome to Inside the Beltway.

A commander-in-chief need not be a learned historian nor a pundit, but he must be familiar with the higher affairs of state and its innate policies; he must know current issues, questions under consideration, the leading personalities, and be able to form sound judgments…10

The role of PME is to teach officers how to reach the higher level of judgement that integrates the aims of policy into its understanding. Someone who can only think like a warrior may be suited for commanding a regiment, but not an army.

Knowledge Will Be Determined By Responsibility

Within this field of military activity, ideas will differ in accordance with the commander’s area of responsibility. In the lower ranks, they will be focused upon minor and more limited objectives; in the more senior, upon wider and more comprehensive ones. There are commanders-in-chief who could not have led a cavalry regiment with distinction, and cavalry commanders who could not have led armies.11

Commanders need not be themselves politicians or diplomats, but they must understand how they think and how war (and the actions within it) will affect their calculus.

An example can illustrate what this means in practice: say a commander is tasked with defending a third country from invasion. They must find a course of action that does not merely defeat some part of the enemy’s forces, but leads the enemy to actually give up on their intent to invade that country. Determining which course of action will produce this effect requires this kind of higher judgment that understands both war (as the instrument) and the enemy with whom it is to interact, in all the particularities of the case. Thus, at the highest level, the commander must also be a statesman, understanding the policies of his government, as well as those of his enemy, and how events and his decisions will impact the attainment of those. Clausewitz is explicit that political responsibility varies by degree, becoming greater as it approaches the commander-in-chief. If a commander cannot grasp the policies that underlie their application of force, they will be increasingly ineffective in their role as their seniority increases. The commander-in-chief (in Clausewitz’s sense the most senior commander) has the responsibility of using military force to convince the enemy to make whatever political concession is sought by policy. There is scant possibility of doing so if one cannot think politically.

“Civilianization”

The civilianization of our uniformed military is a great threat to warfighting ability, and it must end.

That the political view should wholly cease to count on the outbreak of war is hardly conceivable unless pure hatred made all wars a struggle for life and death. In fact, as we have said, they are nothing but expressions of policy itself. Subordinating the political point of view to the military would be absurd, for it is policy that has created war. Policy is the guiding intelligence and war only the instrument, not vice versa. No other possibility exists, then, than to subordinate the military point of view to the political.12

As the purpose of the armed forces is to fulfill the policy aims given to it by civilians, it must be to some extent “civilianized” to be effective. Likewise, it can only fulfill the essential function of ensuring civilians understand the tool which they intend to use (military force) if equipped with a sufficient understanding of civilian government. If officers are trained as semi-literate pedants who cannot utter a sentence without leaning on buzzwords like “warfighter” or “lethality,” they will be (rightly) disregarded when they raise objections for civilian plans for the use of force.

The author goes on to propose criteria for the board of governors of the war colleges, that one must be a retired officer, and that: “These officers must have conclusively demonstrated excellence commanding tactical units.” For all the earlier claims regarding the need for strategic education, the author evidently has no interest in seeking candidates that have demonstrated the kind of strategic insight essential for higher leadership. The bottom line is that his ideal officer seems to be not a Frederick or a Napoleon, but a captain of the hussars, at best a Patton, at worst a Louis Ferdinand or Armstrong Custer. If the war colleges need correction, then I would suggest the first step be to not waste time on individuals like the author or—at the very least—not allow them to graduate with such a poor grasp of the meaning of the word “strategic.”

This cuts to the heart of the matter: the role of war colleges is not to produce warriors—the armed forces have no shortage of them. Their role is to produce decision-makers capable of operating at the strategic level. This means individuals that possess not just knowledge, but a real skill, namely that of rapidly grasping the essence of a situation from incomplete information and making sound decisions based upon it. One need not even agree with Clausewitz’s pedagogical method to recognize the requirements for assuming the responsibility of higher command.

Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. Michael Howard and Peter Paret, with Bernard Brodie, (Easton Press, 1989), 146.

J. T. Sumida, Decoding Clausewitz: A New Approach to On War, Modern War Studies (University Press of Kansas, 2008), 136.

Clausewitz, On War, 140.

Ibid, 147.

Ibid, 163.

Ibid, 140.

Ibid, 146.

Ibid, 145.

Ibid, 159.

Ibid, 146.

Ibid, 145-46.

Ibid, 607.

Brilliant article. I find the current conservative push to model the US military after Russia dispiriting, particularly as one only has to look to Ukraine to see how the "warrior ethos" and "commander knows best" attitude has faired in combat. This attempt is also clumsy and seems intended to generate friction not just within the institution but within the individuals hearing these commands. One can only hope it does not leave a corrosive mark in the long term should this ethos be passing.

Excellent!

If I may, I'd like to add a phrase to your repertoire. In the first para, you talk about the desire of Cynical Publius' to enforce Soviet-style political correctness, but MAGA's own style.

There is a superior term for the Right's version: patriotic correctness.

https://www.cato.org/commentary/right-has-its-own-version-political-correctness-its-just-stifling#

https://www.routledge.com/Patriotic-Correctness-Academic-Freedom-and-Its-Enemies/Wilson/p/book/9781594511943

But of course, its only always only patriotism to the Confederacy, the segregationist South, and the Lost Cause.

Everything else is woke and therefore treason.