Did German Industry Want a War in 1914?

The case of Hugo Stinnes shows they did not and exposes the weakness of a materialist explanation for the conflict

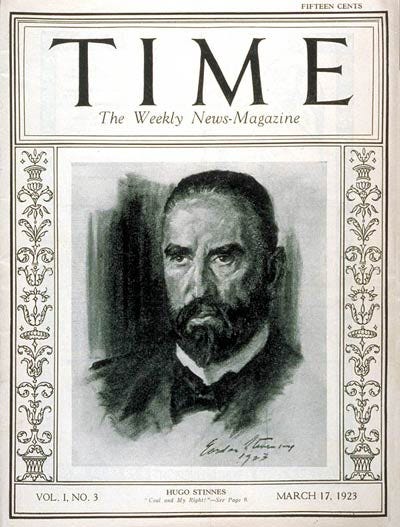

German historian Fritz Fischer provoked enormous controversy in the 1960s by arguing that the German Empire deliberately provoked WWI in a bid to expand its power. Previously, the German public had accepted blame for WWII, but considered Germany no more to blame than any of the other great powers for WWI. Building on the “Fischer thesis,” historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler argued that Imperial German foreign policy was a product of its elites using imperialism to distract the people from a lack of democracy. In a chapter published in Anticipating Total War, “Hugo Stinnes and the Prospect of War Before 1914,” Gerald D. Feldman challenges the idea that the empire’s business elites desired war.

Feldman takes the case of Hugo Stinnes (1870-1924), a titan of German industry and representative of the interests of the financial and industrial elite. Having been born into possession of Ruhr Valley coal mines, Stinnes expanded into international coal ventures, entered the shipping industry, and collaborated with August Thyssen to form the largest power company in Europe. From this towering position, he rubbed shoulders with the political elite of German society, including the Kaiser and his entourage and was therefore among those positioned to attempt to shape state policy towards his own interests.

The Interests of Business

What is significant in this study is that Feldman shows that Stinnes—typical of German business leaders—far from desiring a war, completely failed to prepare for one. “In the years before the war, Stinnes moved into commercial shipping by founding Midgard Lines; his firm had agencies throughout Europe and the Middle East, as well as in the United States and Latin America.” Likewise, he possessed extensive coal mining interests in Wales, Normandy, and Belgium. “The fact was that Stinnes was anxious to make money wherever he could, be it in the Balkans or in Brazil. He took a similar view of business with France, and he was busily buying into French enterprises and ore fields in Longwy and Normandy shortly before the war, apparently without much concern about the testy relations between Germany and France.” This is not the behavior of a man who believed war was in his interest.

Stinnes certainly sought to benefit from German imperialism, appealing to the German government to defend his ability to compete with French interests in Anatolia for instance. However, his interests were specifically commercial, a matter of self-interest rather than imperial aggrandizement. His interest abroad was aimed at gaining market access, not necessarily territorial acquisition. This made Stinnes relatively moderate, far from those who believed Germany needed a colonial empire to fulfill its destiny.

To the consternation of the more aggressively-minded Pan-Germans, he maintained that “the world would now be ruled by economic interest, by the great entrepreneurs and the banks.” His typically chauvinistic view was that the superior qualities of German business would ensure its swift economic dominance of Europe. “Let things develop quietly for three or four years and Germany will be the uncontested economic ruler of Europe.” As such, he viewed the recent confrontation over French interests in Morocco as bad form—overt clashes roused national pride and so ruined opportunities for German business to simply outcompete the interests of other nations. Much has been made of the sense of malaise in Europe before the First World war and the decadence of the “Fin de siecle” particularly the sense in Germany that it was in decline. Yet this is not at all the trend we see from Stinnes. Stinnes viewed German aggrandizement by war as absurd.

From the standpoint of industry, Germany’s rise was continuing apace. This perspective, supported in retrospect by economic historians, spoke against the strategic wisdom of a war. Unsurprisingly, the conviction of the Kaiser that Germany must become a “world power or perish” was a flawed concept—significantly: big business knew it. For the industrialists, German power rested upon them and the fate of nations would be determined by the strength of their industries rather than crude measures of armies and fleets. Who owned a piece of territory on a map was less important than who owned the companies that exploited it.

The Sword of Damocles

The prospect of war was therefore certainly a cause for concern, but efforts at mitigating risk were limited. If business better judged the costs of a war, it underrated its likelihood. Feldman details an attempt by Stinnes to protect his merchant vessels in case of war by seeking neutral ports or else arranging the sale of his ships—potentially to his English subsidiary. However, this was soon dropped as it was made clear to him that Prize Law left no room for this kind of maneuvering. If war came, there was nothing Stinnes could do to avoid the loss of his merchant fleet to the Royal Navy.

Interestingly, in case of war with the Entente over Morocco, Stinnes provided instructions to his merchant captains to seek refuge in St. Petersburg. As late as 1911, Stinnes apparently assumed that war with England would not necessarily mean war with Russia. While not entirely impossible, such a scenario ran counter to the existing power blocs and demonstrated a degree of unreality and wishful thinking to Stinnes’s attitude towards war. Far from desiring it, he (and the class he represented) could scarcely imagine it well enough to seriously prepare for it. Emblematic of the optimism of business, Feldman writes, “Stinnes’s firms… were reporting confidently that there would be peace in the Balkans for a decade following the Second Balkan War.” Further demonstrating this lack of anticipation, Stinnes declined to enter the arms manufacturing industry. Competing with Krupp was considered too risky—hardly the assessment one would make if preparing for war.

The Swing Right

What is confusing about the story of Stinnes is his behavior during the war. While seemingly unable to seriously imagine war before it came, he became a staunch annexationist once it did. Stinnes was a backer of militarists like Erich von Ludendorff and utterly convinced of Germany’s eventual victory. It is not hard to see why one might conclude from this behavior that Stinnes had desired war. What’s more, after the war and towards the end of his life, he became involved in financially supporting far-right causes including the NSDAP and the Beer Hall Putsch. He was far from the only industrialist to tread this path. These actions make it hard to believe in the innocence of industry as a whole in the decision of Germany to go to war in 1914. Nevertheless, in the reams of documents that exist documenting Stinnes’s views before the war, there is no evidence to suggest these attitudes were pre-existing.

The explanation for this apparent reversal is that his views changed as the situation did. On the other hand, we should not be all that surprised that the First World War was sufficient to produce a radical shift in the worldview of those who experienced it. This may not seem remarkable, but it is at odds with a materialist explanation for the First World War. For Stinnes, the world of open trade and industrial competition had vanished in the violence of 1914. While he would have liked the old world to be restored, the universal acrimony made that impossible. Stinnes believed (ultimately correctly) that the nationalist forces the war had strengthened would prevent a return to a liberal trade order. As such, the only option available was that Germany seize the territories needed to ensure its economic strength.

Feldman argues this adaptation to circumstances also explains the ability of Stinnes and other German industrialists to try to ask the victorious Entente not levy high war reparations on the defeated Germany without inconsistency. This, of course, also matched their self-interest, but it aligned with a larger world-view that the interests of business were best suited by a system that enabled trans-national commerce. War and the annexations were arrived at only as a substitute. The world of rational progress that Stinnes and his colleagues had operated in had proved illusory and the dream of a peaceful rise had vanished. The four years of privation, barbarity, patriotism, and propaganda created believers in a new age of struggle. Industry’s drive to German domination of Europe was a product of the war, not a cause of it.

The Responsibility of Industry

If we accept Feldman’s argument that Stinnes is representative of German industry as a class, there is still reason that it must shoulder some blame for the coming of war. Stinnes’s support for Bethmann-Hollweg aligned him with the national liberal bloc and away from more bellicose factions within German politics. Yet, Bethmann still represented a fatally flawed status quo. The chancellor had no intention or capacity to remedy the polycratic dysfunction the Empire’s constitution had bequeathed it. What’s more, while not seeking war, the school of foreign policy Bethmann pursued deliberately courted it. Industry leaders, focusing on the short term, passively accepted an irresponsible system of government. The disastrous reality of a war between the power blocs was unimaginable to them and so they not only failed to prepare for it but could do nothing to avert it. They failed to recognize that the system of government they supported was gravely imperiling the system on which they had founded their prosperity.

Far from architects of the European conflagration, German business upheld the rudderless status quo, trusting that it could continue indefinitely. The trends of the present were mistaken for the march of history, the looming disaster unnoticed in the face of the tumult of the moment. Emblematic of this, into July of 1914 Stinnes continued to be more concerned about preparing for a strike than for war. One might think picketing workers rated a higher threat to his interests in Wales than a blockade by the Royal Navy! Capital in the German empire, far from the engine of a self-aggrandizing war, was literally banking on a long period of peace—Feldman notes the Reichsbank resorted to threatening legal action in an effort to force banks to increase their cash reserves. Long term planning, whether for war or recession, did not come naturally to German business.

The Case of Stinnes

The story of Hugo Stinnes is important not just because of what it tells us about the causes of WWI but as a caution against sweeping materialist narratives. While German industrialists sought to benefit through annexations when war came, that ambition emerged from the shattering of their pre-war worldview. War led to the contemplation of annexations, not the reverse. Stinnes had not believed war would benefit Germany’s material interests or his own. As he maintained before 1914, peace was in Germany’s interest—it is hardly possible to understand his continued investments in Wales, Normandy, and St. Petersburg if this conviction was less than genuine. But even if his material interests had aligned with war, other considerations may well have overcome them. Not having to bury your sons is an interest that cannot be easily valued. Stinnes wrote to his wife in 1913, expressing his hope for a decade of peace “one would hope even longer because of our boys.”

German business did not press the country to war in 1914, though it quickly adopted an annexationist platform and went on to support the far-right in the Weimar period. It was therefore not entirely unjustified when the industrialists felt that politics had come to ruin all that they had been poised to gain for Germany by commerce—even if they could not accept that it was their own nation that was responsible.

There is a haunting lesson in Stinnes’s optimism, particularly his 1913 letter hoping for a decade of peace for the sake of his "boys". It highlights the tragic gap between the rational interests of commerce and the irrational momentum of nationalist politics. Stinnes truly believed that "economic interest" would rule the world and that German industry would achieve total dominance through quiet development rather than crude violence. This text serves as a somber reminder that the "march of history" is often just a series of missed warnings; industry’s failure wasn't its hunger for war, but its passive acceptance of a dysfunctional government that was systematically imperiling the very prosperity they took for granted.

Interesting and well written piece! If I may, I would share my perspective; in my view even if some, such as Stinnes, just wanted international commerce and preferred peace, the fact is that many others directly benefited from escalation and played a role in pushing Germany onto a war footing even long before 14. Krupp, Thyssen, and others had strong financial interests in continued militarization, and large swaths of the Big Biz elite were projecting the National Liberal bloc, which was in various ways a supporter of Germany’s aggressive foreign policy.

and some of Germany’s economic big shots had been preparing for a major war for years. German firms had secured long term contracts for arms production and military expansion so a war economy was already in motion before war was even declared.

and the arg that “business wasn’t prepared for war” because some industries suffered from it ignores that some industries and financial institutions had spent years playing a role in generating a system in which war was being increasingly seen as inevitable and had come to be seen as manageable

and then even just the domestic and international set up they supported itself was something tat increase the war chance. Germany’s economic elite had serious stakes in Austria-Hungary’s (AHE) survival. Many German firms were heavily invested in Austrian and Hungarian industries, and German banks had extended significant credit to the AHE, making its collapse a potential catastrophe for them. and so given how concentrated the political economy was there, its hard to imagine that the big financial and industrial players didnt influence the German leadership’s decision to give Austria-Hungary unconditional support, the infamous "blank check"

And theres more I could list if I spent the time.

Also, and I think this is always very important to point out, guys like Stinnes and other sorts of, like, liberal internationalist sorts, well, they say we dont war were good guys, but what did he want though, well, he and others like him wanted to maintain the status quo in places like the AHE, status quos that were terrible for most of the people that lived there, so even if he didnt want war, he did want the perpetual immiseration of millions and millions of people