"Hybrid War" is a Red Herring

Understanding Russian Aggression and the Perils of Jargon

I don’t like the term “Hybrid War.” The same goes for its close cousin, the “Gray Zone.” You might be surprised that a Clausewitizian isn’t a fan of a concept based on the close relation of politics and war, but as we’ll see, this is precisely the reason for my aversion to the terms.

First, though, it’s worth asking why we should care about the use of jargon like “Hybrid War.” Jargon is useful when it helps to more simply convey a concept, when it is introduced for brevity and clarity. At its best, it is a way to concisely say what you mean, without repetitiously setting terms. At its worst, jargon is instead vacuous, concealing more than it conveys. Regrettably, it is this second kind that is the more common.

This is the case for a number of reasons, but chief amongst them is the pervasive and understandable fear of saying plainly and precisely what it is we mean. Jargon is a useful device with which to shield one’s views from the discomfort of direct scrutiny. With jargon, one can interpose any number of shibboleths and superficial complexities between the meat of the contention and the attention of the reader. By vigorous application of technical terms, we can make ourselves hard to pin down to concrete points that can be directly contradicted, allowing our argument to instead linger in a twilight of vague plausibility.

This kind of jargon, jargon as a smokescreen, is worth wafting away for the sake of honest inquiry. This is all the more so in matters of strategy, an area in which a clear view and practical understanding are essential. In this piece, I hope to subject the concept of hybrid war to this scrutiny and provide an explanation as to why I find the concept as lacking in utility. To begin this endeavor, we ought to start with the obvious question: what is hybrid war?

A Jargon Chimera

“Seemingly a relic of the Cold War-era international order, conventional military campaigns have given way to hybrid warfare involving cyberattacks, information campaigns, and an array of other non-violent pressure.” Thus reads an article published by the Atlantic Council two days before Russia invaded Ukraine. For another definition, there is a NATO report, which provides the description: “an interplay or fusion of conventional as well as unconventional instruments of power and tools of subversion. These instruments or tools are blended in a synchronized manner to exploit the vulnerabilities of an antagonist and achieve synergistic effects.”

If phrases like “fusion of conventional as well as unconventional” and “synergistic effects” somehow did not clear things up for us, there is also an article in The Conversation by Andrew Dowse and Sascha-Dominik Bachmann, which supplies its own definition. They write, “[hybrid warfare] refers to the use of unconventional methods as part of a multi-domain warfighting approach. These methods aim to disrupt and disable an opponent’s actions without engaging in open hostilities.” The distinction of “without engaging in open hostilities” gives us something to chew on, but “unconventional methods as part of a multi-domain warfighting approach” is a description that offers no clarity, even were we to go to the trouble of dissecting it.

When it comes to gray zone warfare, the UK Strategic Command has the following to say: “The term comes from a colour-based metaphor. The idea is that a completely benign or peaceful action carried out by a group or nation can be defined as ‘white.’ Whereas a clearly hostile action, which could be seen as an act of war, can be defined as ‘black.’ So, with that in mind, anything between these would be ‘grey.’ The grey zone is a murky area, consisting of everything which isn’t full-on conflict, but isn’t exactly an innocent act either.”

This is much clearer language, but some scrutiny makes it clear that the common vagueness to these definitions is a product of a fundamental weakness in the concept. After all, many actions are entirely peaceful, but not entirely benign. As Clausewitz observed, at times there may exist such a tension between nations that a very minor incident sparks off a proverbial mine, causing a conflagration entirely out of proportion to the spark itself. The same action, say a border violation or a dispute over fishing rights, may in one circumstance cause only intensified diplomacy, but immediately cause war in another. Is it only in the gray zone in the first case? May we only say so in retrospect, with the act in the moment being in a state of superposition between open and hybrid war? If our only points of reference are benign pacificity and open war, then the more relevant question is: what isn’t hybrid war?

There is Nothing New Under the Sun

It is very hard to see what the idea of the “Gray Zone” can offer us. “Actions that aren’t benign but don’t seek open war” is such a broad category as to be useless. Do tariffs and assassinations have anything meaningful in common merely because they are neither benevolent peace nor open hostility? Using measures that fall between completely benign action and open war to seek strategic advantage has a name: statecraft. It is true that statecraft encompasses both benign action and open war as well, but this is a product of the essential unity of this spectrum of action as part of political intercourse, with no part of it standing outside of statecraft.

Hybrid war might seem to have more utility, as the addition of violence by armed forces brings war into the equation. But in all cases of war, the political intercourse does not cease. War being fundamentally part of statecraft, there is nothing particularly “hybrid” in the use of political means for political ends. Each war is as “hybrid” as another, no matter how limited or extreme its conduct. A war that seems particularly “political” is, in all likelihood, merely a limited war. To mistake this for something novel is liable to produce endless confusion, not least about the nature of war.

Part of the difficulty stems from the fact that, while the term “Hybrid War” is older, it has—in many respects—become synonymous with “what Russia did to Ukraine in 2014.” Deniability and information warfare are its main characteristics, traits that enabled successful aggression in the nuclear era. Understandably, there has been much ink spilled over understanding what happened and how to prevent its recurrence. We will put aside for a moment the question of the suitability of the term “Hybrid War” for this particular phenomenon, and instead ask whether the phenomenon is distinct enough to merit its own term. If we glance at the record of history, we will quickly see that this is not the case.

In 2014, Russia took advantage of the momentary political chaos in a neighboring state to invade and annex a part of its territory without triggering a general war. The term “Fait accompli” describes Russian actions accurately and allows us to more clearly understand them by talking about a true historical phenomenon, of which there are many instances to draw comparison. Rather than accepting hybrid warfare as an innovation in methods, we may see Russian actions as analogous to other instances of faits accomplis.

Translated literally as “a fact completed,” a fait accompli means an action to change the situation which is completed before an opponent can interfere or otherwise respond, so that a new status quo is established which an opponent must choose to contest on the new terms. In practice, a fait accompli is distinguished by conquest without serious fighting, without immediate escalation to open war. The core significance of the fait accompli is in the way it shifts the onus to act. Typically, the onus to act is on the would-be conqueror; he must choose the escalation to war which the defender will be practically obliged to respond to and fight out a war. Because the choice is on the aggressor, he may be deterred.

The fait accompli reverses this: if an object can be seized without fighting, the conqueror may place himself in the position of the defender, with the onus to act on the victim, who now has the task of forcing the aggressor to vacate the seized territories, something difficult to do without open war, especially as the newly seized territory will not be left vulnerable to a reciprocal fait accompli. A fait accompli can fail, simply becoming war. States go to great effort to protect themselves from faits accomplis by communicating as clearly as possible that nothing may be seized from them without immediate open war. They therefore occur only when deterrence fails, with the war-making capacity of states being an intrinsic check on their use.

One might argue that the concept of Hybrid War seeks to incorporate the Russian actions that were aimed at influencing the decision whether to contest the fait accompli, such as the use of deniable forces. Yet, proponents of the concept cannot articulate what it is about these efforts (covert, diplomatic, or informational) that distinguishes them from statecraft. There is nothing more logical or natural than for a state to employ all forms of statecraft to dissuade and deter any effort to reverse a fait accompli. That proponents of Hybrid War believe a diplomatic and informational campaign accompanying military action is such a deviation from the norm as to require its own term betrays a mistaken concept of war in general. Military action is a means of statecraft—statecraft is not war by others means.

The Prerequisites for the Phenomenon

It was not the deniability of Russia’s little green men that allowed them to cross the Ukrainian border without a general war. For a fait accompli to work, the target must be too weak to contest the seizure or to credibly threaten a lengthy war, which is naturally rare. Ukraine was uncommonly weak when Russia struck in 2014 and, even then, Russia failed to achieve its objectives in the Donbas, being forced to commit conventional forces to protect its gains. Many states have the capacity to seize territory from another by surprise attack, but the promise of having to fight a war over it is sufficient to deter aggression. Most states can fight a war—even if outmatched—for at least some amount of time, which permits third parties to weigh in, denying a fait accompli. These third parties have the opportunity to try and prevent the aggressor from aggrandizing themselves, a decision that will only be marginally impacted by the statecraft that surrounded the attempted fait accompli.

It was Ukraine’s particular incapacity in 2014, paralyzed by revolution and with an armed forces hollowed-out by corruption, that gave Russia the opportunity to achieve a fait accompli. No less crucial is that the West had no great interest in Ukraine’s territorial integrity. It is not historically unusual for states to lack interest in preserving the territorial integrity of others, but ordinarily considerations of the balance of power provide an interest in preventing other states from expanding. Russia’s approach required both a weak target and for the opposing alliance to lack interest in seriously contesting its actions. It was these circumstances that were exceptional, not the tactics employed. Focusing on tactics draws analysis away from the political conditions that made their employment effective.

For instance, Russian information operations, such as the claims about separatists and “little green men,” were designed not so much to actually deceive the West as to provide a fig-leaf for Western inaction. Had Russia openly declared that Crimea was theirs by right of conquest, it would have been a direct challenge to the taboo on aggression and so increase the political pressure on the West to take action. By gesturing at Western principles such as the responsibility to protect and self-determination, Russia sought to signal moderation, in the sense that their aims were merely to take territory from Ukraine and not to seek a broader confrontation with the West. Russia’s weak justifications were effective because many in the West were looking for an excuse to not get involved without having to openly abandon the idea of an international order.

We may say that Russian success relied on a measure of self-deception which is typically only present when the matter does not approach vital interests. The intrinsic subjectivity of vital interests and their relevance in this case ensures that fait accompli are risky endeavors. In addition to misjudging the reaction of third parties, a misjudgment of the strength or will of the victim can also cause an attempted fait accompli to simply be the first stage of open war. Success or failure depends more on these external variables than the tactics employed.

Our Chief Weapons are Surprise…

“There’s an old saying in Tennessee—I know it’s in Texas, probably in Tennessee—that says, ‘Fool me once, shame on...shame on you.’ Fool me—you can’t get fooled again.’”

In 1938, Hitler fooled Chamberlain and managed a fait accompli against Czechoslovakia through the deception. But when he tried the gambit again with Poland, nobody was fooled and Hitler got a world war for his trouble. It’s worth recalling the substantial German efforts to frame its aggression as something that was compatible with Western interests and justified by the principles of self-determination and the nation state. The Germans even conducted an extensive campaign of false-flag attacks to justify their war with Poland (most notably the Gleiwitz incident). Yet, these efforts proved entirely pointless as German actions had made their intentions clearer than any information operation had the power to conceal, and the Allies declared war.

The annexation of Crimea was possible because it was unexpected and because Western leaders were more confused than threatened by it. The West consequently proved keen to make excuses for the Russians. While changing borders by force was strongly opposed, the border between Russia and Ukraine was perceived as less than wholly legitimate because it had been drawn during Soviet rule. While the West had not forgotten Hitler’s deceptive claim to merely be uniting one people in his territorial aims, the idea of a singular nation-state still holds currency, meaning Russian claims to the limited ambition of unification with ethnic Russians were given some credence. The West was therefore inclined to interpret Russian aggression as an aftershock of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, as a border skirmish to be managed rather than a serious challenge to the world order. This too may be paralleled with the policy of appeasement, mistaking Hitler’s aggression for a mere alteration of the borders delineated at Versailles rather than a bid for world power.

Yet, even in cases of grave mistakes like these, states tend to hedge their bets. The Munich Agreement was followed by Western rearmament. The 2022 invasion of Ukraine was not unexpected and met anything but ambivalence. Today, it is scarcely imaginable that any further Russian aggression would meet a reaction comparable to the annexation of Crimea. The same tactics—even more sophisticated versions of them—would fail to achieve the same effect because their initial use destroyed the political circumstances that had made them effective.

Perhaps more importantly, states with the capacity to resist are not vulnerable to a fait accompli. If Russian forces cross the Estonian or Polish borders the shooting will start, regardless of whether the Russians claim their forces are separatists or “little green men.” When the shooting starts, there’s no question of “Hybrid War.” There’s just a conventional war and ordinary decisions about involvement apply. A fig leaf is only useful if it is large enough to cover anything and if anyone is actually interested in using it. Russian claims about separatists and volunteers are not enough to affect the calculus when serious interests are at stake, as any attack on a NATO member would constitute. If a country is abandoned to Russian aggression, it will have little to do with the use of “‘Hybrid War” tactics.

Schelling and the Last Clear Chance

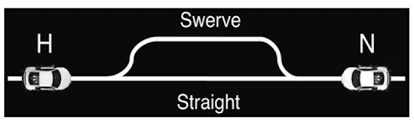

In criticizing the emphasis on techniques inherent in the framework of “Hybrid War,” a brief digression into game theory is necessary to discuss its value in a nuclear world, where open war between nuclear powers carries with it the risks of escalation. Writing on nuclear strategy, Thomas Schelling invoked the example of the game of chicken: two drivers drive towards the other on a collision course. The first to swerve out of the way is the loser. A collision can happen in the game of chicken, despite that being disastrous to both sides, if both players believe that the other will swerve and so maintain their course. This is an analogy for the way states can end up at war despite neither desiring it. This idea of unintentional collision is a concept vital for explaining how nuclear war is possible in the age of mutually assured destruction where the consequences are universally disastrous.

Within this framework of accidental collision, Schelling investigates the means that players have to manipulate the risk of disaster to apply pressure to the other side and induce them to “swerve” or otherwise give in. What he finds is that, counterintuitively, it is advantageous to cede the initiative, to tie one’s own hands. For example, in a game of chicken, if a player throws their steering wheel out of the vehicle, making it impossible for them to swerve, they now have an advantage over their opponent because they can no longer easily give in. They have placed what Schelling calls the “last clear chance” to avoid disaster on the other side. Once your opponent has thrown out their steering wheel, throwing out your own won’t help you at all, since you’re now the only one able to prevent the collision. Once you’re left with the last clear chance, you can either give in, or accept the now very high risk of disaster, knowing your opponent cannot reduce the odds, even if they lose their nerve.

Reality is not so clear cut, but the concepts of risk of disaster and the “last clear chance” to avoid it are useful for understanding the mechanics of escalation. The classic example in practice is the American blockade of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The blockade left the Soviets with the choice to either run it and accept the escalation to a higher risk of mutual catastrophe (as American ships shot at Soviet vessels) or to back down. We might say that a Soviet attempt to run the blockade would put the choice of escalation back on the US of whether to actually sink the Soviet ship, but the order to blockade Cuba delegated that decision to commanders on the scene, taking it out of the president’s hands in the moment. By delegating authority to sink Soviet ships, the proverbial steering wheel was more or less thrown out. The Soviets knew that if they attempted to run the blockade there was little opportunity for the American president to prevent the shooting from starting, even if he lost his nerve at the last moment. This self-limitation left the last clear chance with the Soviets and so put them at a disadvantage.

The Intrinsic Weakness of Deniability

Returning to our subject, “Hybrid War” tactics, specifically the use of deniable forces or proxies, has the intrinsic weakness of allowing your opponent to force the last clear chance onto you. This was vividly demonstrated at the 2018 Battle of Khasham: the Russian proxy, Wagner Group (along with Syrian paramilitaries), engaged US-backed Kurdish forces in Syria. Unfortunately for the Russians, this included embedded American personnel. The Americans asked the Russians whether Russians were involved in the attack. In accordance with using deniable forces, the Russians denied any involvement. This, however, gave the Americans total freedom to bomb the paramilitaries and any Russian “mercenaries” involved. The Russian death toll ranges from 60-300, in return for no US casualties and one wounded Kurdish fighter.

By denying the affiliation of Wagner Group, the last clear chance to avoid escalation was left with the Russians. To interfere with American strikes against Wagner, Russia would have had to be willing to use its regular forces against America’s, something that would generally be called an act of war, which is precisely the opposite of the intent of Hybrid War tactics. The only effect of their employment was to grant the Americans a free hand against the Russian proxies. This may give us a clue as to why their employment in 2014 seemed novel: the circumstances of their effectiveness are rare.

With US forces embedded, there was a strong motive against inaction. The Russian denial of responsibility in fact made the Russians vulnerable to a fait accompli—US airpower destroyed their proxies and put the onus on the Russians to escalate. This illustrates not only the danger, but that the role of these proxies is not to actually conceal Russian involvement, but to provide a pretext for inaction. The US was not interested in inaction, and so the Russian denial of responsibility only served to ease the decision to strike. Denying the attribution of forces allows your opponent to act against you directly and put the decision on you whether to escalate towards a conventional conflict or leave the matter be. The use of deniable forces in the annexation of Crimea was a measure to ease the Western decision towards inaction, but the danger in this technique is intrinsic and therefore suitable only in particular circumstances.

The Analytic Danger of Hybrid Warfare

The great danger in becoming preoccupied by the apparent innovations of “Hybrid” or “Gray Zone” warfare is in neglecting the true schwerpunkt of the matter: the basic questions of conventional deterrence and political will. Through this lens, it is abundantly clear what made the seizure of Crimea possible, and understand that it was the political circumstances that made such tactics effective, rather than the tactics themselves. Whether Russia believes it can seize the Baltics depends upon its understanding of Western interest and its assessment of the Baltic capacity for resistance. The adaptation of Western militaries to these “new” tactics hardly rates as a concern.

If we are at a point where it is conceivable that Western governments will choose to abandon states in Eastern Europe to Russian domination, this has very little to do with Russian tactics and everything to do with changes in the Western political landscape that have destroyed the consensus of an international order. Many right-wing parties are openly contemptuous of the concept, ironically internationalizing the “America First” slogan.

Proponents of the “Hybrid War” concept will attribute this change to Russian interference in Western politics. This interference is very real, but it would be a grave mistake to overstate its impact. Russian interference fanned the flames, but the forces that devoured the consensus are organic to Western societies. Countering Russian influence will be insufficient to restore this consensus against aggression. If individuals and parties who like Russia and despise the liberal international order come to power, Russia may act freely. Whether Russia seeks to cross the Estonian border with hybrid forces or regular ones will not determine whether deterrence holds. It depends entirely on whether the Russians believe Western governments will act. If the Americans, Germans, and French all elect leaders who say they would never shed a drop of blood on behalf of another nation, no tactics are not why Russia will have a free hand. The fact cannot be escaped that deterring Russia requires combating the right-wing nativist movement across Western societies.

As Clausewitz wrote, “it is most dangerous to confuse the small with the great and to be led by the former.” It is understandable why traditionally nonpartisan organizations focused on strategy and foreign policy would reach for the elements that remain in that vein, namely Russian methods in the 2014 annexation. While these are worth examining, the bounded nature of the investigation limits its utility, as it cannot remain nonpartisan if it acknowledges the elephant in the strategic room: that there is an increasingly influential movement in Western countries that is openly hostile not just to the liberal democratic order, but to Enlightenment values in general.

There are no innovations in tactics that can protect against this. Anticipating hybrid war tactics or combating Russian influence in Western politics is not enough to secure deterrence. Nothing short of a restoration of the consensus for a liberal democratic order can achieve this. This centrality of domestic politics is something uncomfortable for national security professionals to reckon with because it is incompatible with the tradition of nonpartisanship in their profession. But nonpartisanship is no virtue when parties represent the utter rejection of the liberal world order.

So let us speak plainly of Russian efforts to subvert and overturn liberal democracy, discussing their tactics in various facets of statecraft directly, without the faux novelty of the “Hybrid War” framework. Let us, in both reflection and anticipation, always keep in view the centrality of political circumstances. Let us recognize that the business of national security cannot remain aloof from questions of domestic politics when the very idea of liberal democracy is threatened. For if democracy dies at home, what nation is there to secure?

My belief about the whole "hybrid warfare" was that it was an attempt by COINistas to maintain their grip on power in Western national defense circles after the heydays of GWOT (2003-2008 for Iraq, 2001-2011 for Afghanistan, 2015-2018 for Syria). Gradually after 2016 the COINistas increasingly began to lose power and influence as the future threats are Russians and Chinese.

However the irregular warfare / special operations circles could extrapolate and invent new terms. Borrowing the whole "4th generation warfare" theory and slap new paints on (actually the original piece about "4th generation warfare" in 1990 did make more sense). If you've read Sean McFate's book on "the new war" (please don't), he basically says that US conventional advantage is some immovable object and the only thing that matters is "hybrid warfare". It does suit their institutional goals of maintaining relevancy.

The theory had some bizarre denominations over the years such as the worshipping of Soleimani and Gerasimov. One could write an entire treatise on all the worst excesses of the whole Hybrid Warfare era.

However there's also a political aspect of "hybrid warfare", western national leaders become increasingly weak and indecisive with regards to national security. Populace grew complacent and believed in the End of History (honestly I hate the 1990s because of the kind of delusional thinking that seemed to last forever). What "hybrid warfare" actually says was that the military and national security professionals should get greater say in media, economy and politics. The natural conclusion of which would be an IRGC-style deep state that would inevitably bankrupt the nation for their many petty goals.

Hybrid warfare ultimately is the fantasy where the defense of a state solely rests on its army and intelligence apparatuses. It takes the whole country, yet no politician is willing or able to do so.

I think those two Chines Col's that penned the essay/book titled "unrestricted warfare" nailed it. Of course, the PLA Officers, would never have been allowed to publish that work unless it was tacitly approved by party leadership, but i digress. When Clausewitz wrote - I paraphrase - that we need to unequivocally know the type and character of war we are about to engage in, i think using the term unrestricted warfare captures the essence. If we feel compelled to make the doctrinal verbiage contemporary, then how about something like Unrestricted Multi Domain Operations - Simple!