No One Should Have Been Surprised By Russia's Defeat in Ukraine

How those who predicted a swift Russian victory got the war very, very wrong.

Hindsight is twenty-twenty, and to say that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was a poor decision after it has already failed in its purpose is not particularly enlightening. Instead, where hindsight can be useful, is in looking at whether predictions to the contrary were well founded. I will argue that they were not and that Ukraine’s successful resistance should have been anticipated. Therefore, I will provide an explanation, based on Clausewitz’s writings, as to why informed observers correctly believed Russia would fail to conquer Ukraine quickly or easily.

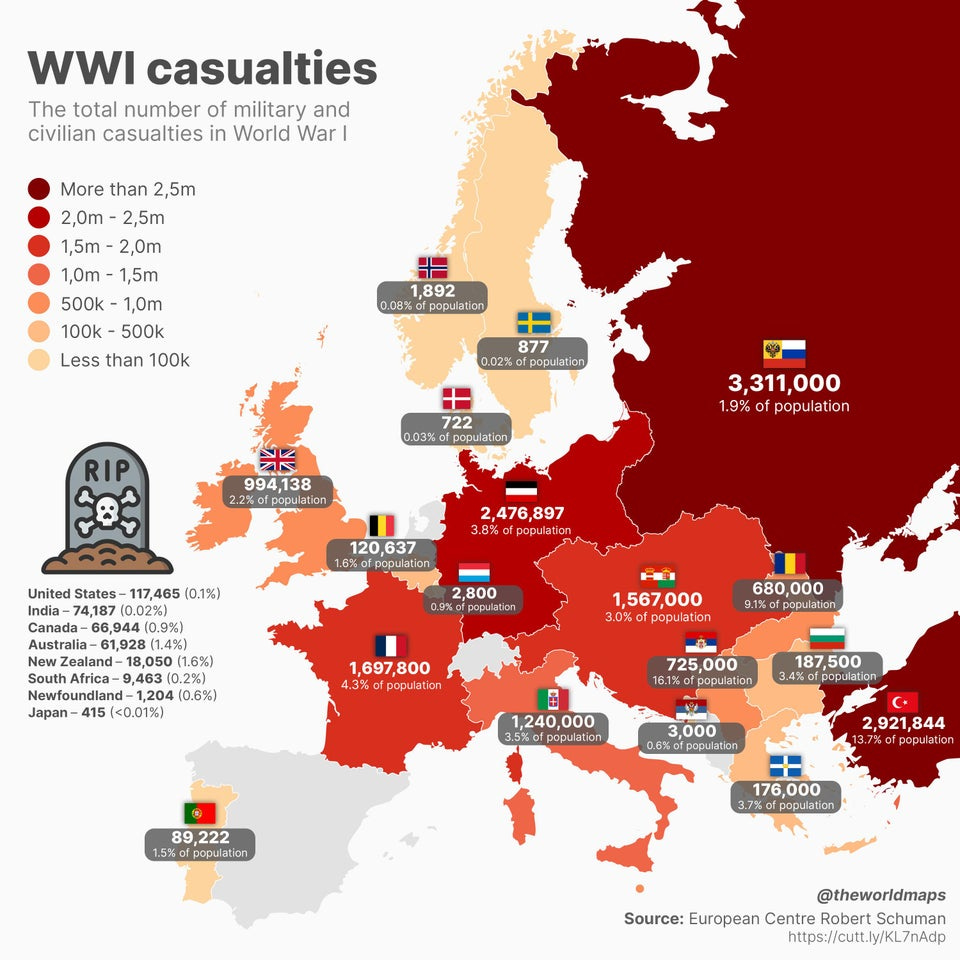

The basic fact of it is, invading a country is difficult. As the World Wars demonstrated, nations will sacrifice men and women by the million before capitulating. Even in defeat, resistance can make occupation untenable over the long term. Insurgencies have proven successful everywhere from Afghanistan, to Yugoslavia, to Portugal. The point is not that nations are inherently unconquerable, merely that subduing a nation in arms requires extraordinary effort. The strength of a nation in its own defense was observed by Clausewitz, ironically, in Russia’s defense against Napoleon in 1812. In studying this campaign, Clausewitz observed how the defender could utilize friction to attrit the enemy to utter powerlessness. So long as a government could endure suffering without making peace, it could materially and morally exhaust the invader, while relying on interior lines and the unconditional political support brought about by a war for national survival.

There are, however, three events in recent history that would give the Russians reason to believe otherwise: the first and second Gulf Wars, and the 2014 annexation of Crimea. These cases bucked the trend of arduous conflict and suggested to Russian leadership that a new paradigm had emerged, in which force could profitability revise the international order.

Most comparable to the 2022 invasion of Ukraine in military terms was the second Gulf War. In 2003, a US-led coalition invaded Iraq and ended the rule of Saddam Hussein, beginning a lengthy and costly occupation. Iraq in 2003 was a nation of 25 million people, 20% larger than Germany in terms of area. A number of factors meant that it was ultimately unable to generate combat power proportional to this base. To touch briefly on the subject, Saddam Hussein’s paranoid and arbitrary rule prioritized regime security over the strength of the armed forces. Saddam had severely divided the country, which fatally weakened morale. In addition, the defeat Iraq had suffered in the 1993 Gulf War not only materially weakened the Iraqi Army but utterly demoralized it. The prolonged and crippling sanctions imposed in the aftermath prevented regeneration from this defeat.

When war came once again, the Iraqi Army, generally speaking, chose not to fight. Russia, it appears, came to the conclusion from the Iraq War that even a well armed nation cannot withstand a great power in the 21st century. The difficulties encountered by the coalition in the ensuing occupation could be dismissed by the Russians as a weakness of democracies to domestic discontent. While Iraq was alienated from its occupiers by language, culture, religion, and sheer distance, Ukraine was on Russia’s doorstep, and had many of these in common. Besides, Ukraine had been under Russian dominion within living memory, surely a return to that state of affairs would be unlikely to engender bitter resistance? It was only with this kind of self-deception that the Russians were able to convince themselves of the wisdom of invading Ukraine.

In its invasion of Ukraine, Russia neglected to recognize the fundamental difficulty entailed in the invasion of a country. Russia ignored the conditions that caused the collapse of the Iraqi Army and instead ascribed it entirely to the superiority of a modern military, something it believed to possess. This lesson was seemingly vindicated by the ease with which Russia annexed Crimea and significant parts of eastern Ukraine. In drawing these conclusions, the central axiom of Clausewitz had been neglected. Both Iraq in 2003 and Ukraine in 2014 were in positions in which internal politics precluded the serious prosecution of a war of national defense. These conditions were absent in 2022 when Putin decided on a course of war. Ukraine’s institutions were not shaped around maintaining the power of a dictator, unlike Iraq’s. Instead, though struggling, aspirations of European integration and the threat of Russian domination gave Ukrainian institutions broader public support than they could otherwise expect. Independence and democracy were hard-won prizes that would not be soon surrendered.

It required exceptional circumstances for Iraq’s resistance to disintegrate in the face of the coalition, none of which were reproduced in the prelude to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It is the rule that nationalism gives states a truly tremendous power to resist foreign domination, even when there exists a vast gulf in capabilities. Whether or not Russia intended to destroy Ukraine as a coherent state, Ukraine perceived the invasion to be a threat to national survival. Understandably, when another country’s armored columns and gunships are racing towards one’s capital, citizens fear for their nation, regardless of what statements the invader has made. Russia’s actions themselves fueled a war of national resistance for which it was unprepared.

Had Russia not consistently learned the wrong lessons from the wars of recent history, the Ukrainian reaction to a threat to national survival would not have come as a surprise. The simple fact that Ukraine possessed in 2022 nearly twice the population that Iraq did in 2003 illustrates the fundamental nature of Russia’s underestimation. Not only did Ukraine’s sheer size give it greater capacity for resistance than Iraq, but it had suffered from virtually none of the crippling ailments that had dogged Saddam’s Iraq. Ukraine had not suffered a decade of devastating sanctions. Rather than entering the war with a hobbled and isolated economy, it had a growing, interconnected economic base, and friendly neighbors through which it could import that which it could not produce. Before considering international aid, Ukraine entered this war with its economic fundamentals secure. Pain was inevitable, but collapse was not in sight.

Iraq was faced with the overwhelming force of an international coalition that could offer to rid it of a regime of inhuman brutality and did precious little to earn popular support. Whether the promises of the Americans were believed, few were keen to fight and die for the preservation of Baathist rule. In contrast, Ukraine faced invasion by its old imperial overlord, explicitly threatening its hard-fought aspirations of European integration and seeking to return it to a state of colonial subjugation. It begs the question why Russia should be exempt from the consistent failure of European powers to maintain control over their colonial empires.

As a result of these fundamentals, well informed observers had good basis to expect Russia to encounter disaster upon its invasion of Ukraine. Western observers that predicted a swift Russian victory can plead to the formidable appearance of the Russian army based on the assessments of Western militaries. The rampant corruption in Russia was well known, yet its impact on Russian military readiness was frequently understated. While overestimation is safer than underestimation when it comes to adversaries, the failure to anticipate the success of Ukraine’s defense was not without cost. Many Western nations were unprepared to support a successful Ukrainian defense, a fact which cost Ukrainian lives.

Some who predicted a Russian victory may seek to defend themselves by appealing to the unexpected neglect of basic military principles. Who would expect the Russians to be this incompetent? While this is a partial defense, the Russian decision to invade can only be explained by the expectation of a swift and easy victory. That is to say, the fact that the invasion happened in the first place was indicative of a detachment from reality. Russia hoped to subdue a nation of 40 million people with an army of 300,000, including conscripts and paramilitaries. Even had Russia possessed the world’s most effective military, this would have been a herculean undertaking. As will be discussed, there were good reasons before the invasion to doubt that Russia had a military remotely as effective as it claimed.

“An army that maintains its cohesion under the most murderous fire; that cannot be shaken by imaginary fears and resists well-founded ones with all its might; that, proud of its victories, will not lose the strength to obey orders and its respect and trust for its officers even in defeat; whose physical power, like the muscles of an athlete, has been steeled by training in privation and effort; a force that regards such efforts as a means to victory rather than a curse on its cause; that is mindful of all these duties and qualities by virtue of the single powerful idea of the honor of its arms – such an army is imbued with the true military spirit.”

Clausewitz, here, provides a clear and succinct portrait of a healthy army-and a striking contrast to the Russian military. From this description, it is clear why it was evident to well informed observers that the Russian army could not be a healthy one even before its weakness was exposed in the invasion of Ukraine. Successful experience in combat, realistic training, and faith in the institution of the army are Clausewitz’s prerequisites. In Putin’s Russia, these prerequisites were impossibilities.

Russia has had only limited combat experience to inure its forces to the realities of war and develop a broad base of experience. The stratified culture of its army and its weak NCO corps means that the experience it has gained could not proliferate. Nor has the Russian army won the victories necessary to both develop successful procedures and create a sense of the army as a “victorious army.” Its brutal occupation of Chechnya and its terror bombing in Syria do not provide the combined-arms expertise needed to wage modern war effectively.

Corruption at the highest levels of government create an environment corrosive to the honesty needed for an army to conduct realistic exercises. In such an environment, even if realistic exercises were carried out that would have revealed the institutional flaws, corruption disincentivized reporting these deficiencies.

“The mere fact that soldiers belong to a ‘regular army’ does not automatically mean they are equal to their tasks. Military spirit, then, is one of the most important moral elements in war.“

Clausewitz also may as well have been writing with knowledge of the policies of the modern Russian Army when he writes that “The mere fact that soldiers belong to a "regular army" does not automatically mean they are equal to their tasks.” The filling out of units with conscripts and reservists meant that very few units of the Russians Army were capable of carrying out the complex maneuvers that full-strength, professional, units are capable of in map exercises. This practice fed delusive attitudes which corruption ensured field exercises could not dispel.

A consequence of Putin’s kleptocracy is the fact that there is an abysmally low level of trust in institutions in Russian society. Soldiers do not trust each other, and their superiors, even less. The knowledge that corruption permeates every level of society is inestimably corrosive to morale. It’s difficult to maintain “military spirit” when graft is prevalent and trust is consequently absent. In an environment of corruption, cynicism is rampant and indiscipline inevitable. With the Russian military existing in such an environment,

Ultimately, it was not a miracle that Ukraine humiliated Russia. Considering the fundamental circumstances of the war and the known deficiencies of the Russian armed forces, this was the most likely outcome. Those who predicted a swift victory for the Russians could only do so from a place of ignorance of the fundamentals of war and the depth of Russian corruption. In light of the strong expectation of a Russian victory before the outbreak of the war, there are a number of lessons that have been reinforced by the outcome.

The nation-state has proven its extraordinary capacity for resistance to foreign domination. There was a mistaken belief that Ukraine being relatively young and poor would counterbalance this capacity. There was also a deep-rooted overestimation of Russian military capacity. While few anticipated the extent of Russian incompetence, Russian pretensions to peer status with Western forces was generally accepted by many observers. This should not have been the case, given the well-publicized corruption tainting Russian society. A military is an institution like any other, and a corrupt society cannot produce world-class institutions. From these lessons, we can hope that the free world is never again caught flat-footed by a nation’s ability to defend its existence and will instead be ready to immediately supply all means necessary to reject attempts to reassert imperial hegemony and preserve the principle of self-determination.

For a “Klauzewitz scholar”, it’s amazing how narrow and narrative-driven this article is. It fails to understand what the strategy in 2022 was - and what was the main goal of the campaign that year, how the strategy was changed in 2023 and later on. The author does not understand that throughout the conflict Russia always had strategic initiative - being able to execute and pace operations at the time and place of its choosing. The rest follows. Another armchair general without an army or a staff. Wouldn’t be trusted with a platoon.

Russia is winning the war, it is just taking longer due to their ineptitude.

This is another neocon proxy war in which their pathological world view is promoted at the cost of many lives other than their own.