The Dilemma of Ukraine's Offensive

Will Ukraine choose the approach of attrition or of annihilation?

To discuss the counter-offensive, it is important to distinguish the two forms of operation. It is generally accepted that there are two approaches to operations, with the first being positional warfare and the second being maneuver warfare. Ukraine must choose between them in its upcoming counter-offensive, which serves as a useful case for better understanding them. The first approach, positional warfare, is associated with attrition, the wearing down of the enemy until they’re incapable of resistance. The second approach, maneuver, is associated with annihilation, in which an enemy is rendered helpless through a decisive battle.

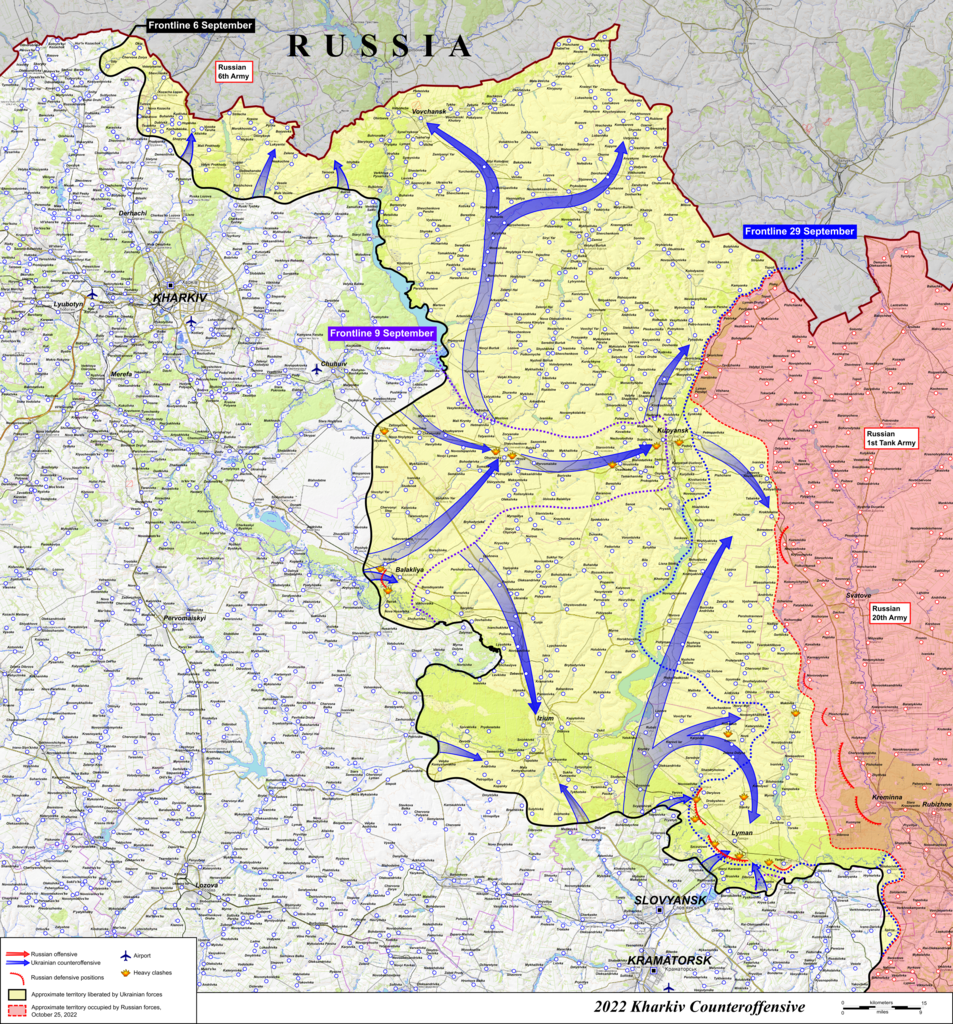

The war in Ukraine thus far has already provided very useful examples for illustrating the distinction. In 2022, Ukraine conducted two major counter-offensives; one directed at Russian forces in the north of the country, near the city of Kharkiv, and one directed towards Russian forces in the south of the country, on the Western side of Dnipro near the city of Kherson.

The Kharkiv offensive was a case of maneuver warfare. Ukraine quickly overcame Russian prepared defensive positions and exploited this breakthrough to cause havoc behind the frontlines. The relentless tempo of Ukraine’s advance successfully paralyzed Russia’s ability to contain the breakthrough, leading to a general breakdown of order in the Kharkiv sector and forcing the Russians to withdraw across the border. Even in Humvees, the ability to outflank and threaten to cut off Russian forces proved decisive.

The case of Kharkiv clearly illustrates the potential of success in maneuver warfare. Once Ukrainian forces had breached the front, their presence behind the lines spread panic among the Russians and forced a disorganized withdrawal. Ukraine recaptured vast swathes of territory and inflicted serious casualties and captured large stocks of equipment. In a very short time, Ukraine accomplished all this and with proportionally few losses.

The counter-offensive to recapture Kherson, on the other hand, was a case of positional warfare. Positional warfare is based on forcing the enemy to choose between holding territory and suffering disproportionate losses. This is possible due to the positional disadvantages involved in actually occupying that terrain. The position left Russian supply lines open to artillery and HIMARS attack. So long as they continued to occupy that position, the Russians would continue to suffer attrition. At the same time, Ukraine, being a position that was not exposed, did not suffer equivalent losses. As a result, the longer the Russians chose to occupy the terrain, the more the balance of force swung in favor of Ukraine. Not only did this mean that, strategically, Russia was becoming weaker relative to Ukraine, but that the force occupying the terrain was becoming increasingly vulnerable to direct assault by Ukraine.

Ukraine utilized the geographically exposed nature of the Russian position around Kherson to attrit the occupying forces to such an extent that they were forced to withdraw or run the risk of being destroyed. Crucial to this were both Ukrainian long-range fire capabilities, such as the HIMARS, and the existing logistical constraints on the Russian position across the Dnipro river.

Positional warfare cannot promise as swift or as decisive a result as maneuver warfare, but it is less risky. A mobile offensive faces the challenge of maintaining the initiative and fending off the efforts of enemy reserves to stymie the offensive. However, a positional offensive has the advantage of forcing a dilemma on the enemy. When faced with a positional attack, the enemy can withdraw, can attempt to hold the position at any cost, or must attempt an offensive of their own in order to change the positional advantage. The attack does not need to rely on successful exploitation or a superior tempo of operations in order to be successful positionally. Instead, it must merely attain the advantage of a position, and press it home, until the enemy either withdraws or is destroyed.

The positional approach has certain advantages for Ukraine. Ukraine has been feverishly seeking to reform its armed forces since 2014, yet the process was far from complete when the Russians invaded in 2022. As a recent article from “War on the Rocks” by Erik Kramer and Paul Schneider noted, Ukraine still struggles with integrating the vast array of NATO and Soviet equipment, conducting combined arms operations, and in lower level leadership.To go over each point briefly, ensuring forces on the frontline get what they need to remain combat effective takes longer than it would in a fully standardized army, making it challenging to sustain operations. As well, combined arms operations are inherently incredibly difficult, requiring extensive practice in coordination between branches. Ukraine has not had the opportunity to conduct training on the necessary scale. The outbreak of full-scale war has led to an expansion of the armed forces, meaning many individuals lack the requisite formal training. This ties into Ukraine's problems with low level leadership. As an ex-Soviet state, Ukraine inherited a doctrine that was based on centralized leadership and placed insufficient emphasis on the initiative of junior officers. In addition, Ukraine did not inherit a non-commissioned officer corps comparable to that of Western armies. It has made progress towards constructing one, but the process was far from complete at the outbreak of war.

These difficulties make maneuver warfare particularly challenging for Ukraine. The ability to rapidly and efficiently resupply units is essential for mobile operations. As units advance, they inevitably attrit men and equipment, requiring replacements to be brought into the newly captured territory in order to both keep advancing and defend against counter-attacks. Without the ability to efficiently conduct combined arms warfare, mobile operations are a challenge; infantry, artillery, armor, and air assets must be tightly coordinated in order to break through prepared defenses. Devolved decision-making is essential for a high tempo of operations and mobility needed to successfully execute maneuver warfare.

In addition to these considerations, there is the fact that air superiority is generally considered a prerequisite for mobile operations. The “flying artillery” of close air-support is essential for both compensating for a force advancing outside the range of its own artillery support and in suppressing enemy artillery. Ukraine’s Kherson advantage was successful without air superiority largely because of its positional nature. The slow pace of advance ensured availability of artillery to support it. The Russians were the ones that needed to take action to relieve the pressure on the Kherson salient, therefore parity in the air was sufficient for Ukrainian purposes.

In the Kharkiv offensive however, there were mobile operations, which necessitated air support. At the same time, as the situation turned more desperate for the Russians, they deployed their own air assets. Both air forces suffered losses. The exact ratio of losses is unclear, but future use of maneuver by Ukraine will require a willingness to endure losses in the air and contest the airspace at least at the decisive point of the offensive.

I bring up the host of challenges facing Ukraine not to argue that Ukraine will conduct its offensive on positional terms rather than through maneuver. The fact of the matter is that mobile operations are invariably more difficult than positional ones. Yet, for all their risks, they promise proportional rewards. Ukraine will certainly take into account the challenges it faces when weighing its choice between mobile and positional operations, but it will also weigh the challenges its enemy faces and the opportunities that they afford. It also should not be forgotten that, for all its deficiencies and for all the difficulties involved, Ukraine did successfully carry out mobile operations around Kharkiv. If Ukraine assesses Russia to be in a similar position of weakness, it may choose the approach of maneuver, particularly as it is emboldened by Western arms and Western training.

The choice between maneuver warfare and positional warfare is therefore not a matter of right or wrong, but rather a question of risk tolerance: whether it is more strategically advantage to pay the price needed to gain a positional advantage and then leverage it, or to accept the risks of mobile operations and trust one’s own strength (or the enemy’s weakness) to deliver positive results out of proportion to the costs.