Ukraine and the Lessons of Blitzkrieg

The popular understanding of the German victory in the West is based on more myth than fact—the truth speaks to principles of enduring relevance to the war in Ukraine

In 1939, the German Army crushed Poland in a matter of weeks. While there had never been any real hope that the country could hold out against the Germans given its encirclement on three sides, the pace of the victory was nevertheless astounding and gave a slight shock to Western powers that were prepared for a continuation of the First World War. Not enough of a shock for them to truly revise those assumptions however, as a little under a year later, they found themselves defeated even more astoundingly than the Poles had been.

“A complete battle of Cannae is rarely met in history. For its achievement, a Hannibal is needed on the one side, and a Terentius Varro, on the other, both cooperating for the attainment of the great goal.”

The German victory was in part the product of unique circumstances that make it inapplicable as an example to all other future wars. Never again will an army be surprised by the mobile potential of mechanized divisions and close air support, nor will it attempt to manage a campaign in the style of the French in 1940 that made them so vulnerable to a rapid advance. For that reason, whatever the serious flaws the Russian army of today possesses, Ukraine cannot hope for victory as decisive as that of the Germans in 1940. To achieve a historic victory as in the Battle of France, the enemy too must play their part and make mistakes of a historic magnitude; as Schlieffen wrote, “A complete battle of Cannae is rarely met in history. For its achievement, a Hannibal is needed on the one side, and a Terentius Varro, on the other, both cooperating for the attainment of the great goal.” It is too much to hope that the Russians will play their part.

Nevertheless, the case serves as a useful point of comparison because of the many things the Germans did right. The lessons in creating a breach in a fortified line and the conditions of an army that make it able to conduct and exploit breakthrough operations are worth examining. In his book, The Blitzkrieg Legend: The 1940 Campaign in the West (link to Amazon, As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases), Karl-Heinz Frieser argues that the so-called “blitzkrieg” was not a masterplan. While certain armored theorists envisioned large-scale mobile warfare, this was not the campaign plan that Germany went to war with. However, competence in basic factors allowed for a decisive breakthrough, despite the numerous advantages that technological advances in firepower had provided the defender which allowed these armored visionaries to implement their vision of mobile war.

In this article, I will discuss the factors that enabled German victory in 1940 and examine their continued importance for Ukraine’s efforts to liberate its occupied territories. These factors are, in order of discussion: Training. Initiative, Concentration, Deception, and Risk.

Training

Materiel deliveries to Ukraine have been the topic of political discourse and media attention. However, far less attention has been given to the training programs supplied by the West. While artillery rounds are essential for sustainment and airpower necessary for combined operations, of equal importance is training. Expensive equipment such as Patriot Missile batteries and “game changers” will not prove as important as ensuring Ukrainian forces are better trained than their Russian counterparts.

Yet, while the German Army went from victory to victory in the first half of WWII, there is a fact that is often overlooked in the broader narrative: the German Army in 1939 was in shambles. If not for the total passivity of the Allies in the West and their many advantages over Poland, the Germans would have run into serious difficulties. In the aftermath of the invasion of Poland, German high command lamented the poor state of discipline of its forces and noted that the Panzer divisions suffered serious mechanical and supply problems. The rapid expansion of the army had left much of its equipment and personnel well below modern standards.

However, the Allies assumed the strategic defensive, allowing the Germans to correct these errors. Thus, the German Army underwent a radical transformation between the end of the war in Poland and the start of the attack on France. Of central importance was combined arms training. The Luftwaffe assigned liaison officers to the army and exercises emphasized the coordination between air and land forces so as to be able to use close air support as “flying artillery” when the offensive advanced beyond the range of friendly guns.

This is a lesson Ukraine must take to heart. Training must take place across branches. The provision of Western fighters, even in substantial quantities, will not be enough to achieve a breakthrough. Coordination between air and ground must ensure that airpower is in the right place at the right time. Airpower must be able to make up the difference in firepower and prevent the advance from getting bogged down. If a breakthrough force is unable to get airpower to suppress enemy strongpoints fast enough, it will inevitably be contained and subjected to punishing counterattacks. An attack needs momentum, which comes from speed, which in turn comes from firepower. Thus, an attack can only achieve operational level effects with close coordination with the air forces.

The implementation of the lessons learned in the Polish campaign was important, but not nearly as important as merely ensuring a high standard of training. At the outbreak of war, many of the men the Germans took to war were scarcely trained at all. The Germans made excellent use of the phony war in drilling these raw recruits to contemporary standards. By contrast, the French army at times had its soldiers take part in agricultural work. This is not because the French were careless, but because they believed that military technology was in a position that a rapid decision was not possible and that industrial and agricultural factors would be decisive in the ensuing attritional struggle.

The Germans, despite their commitment to a rapid decision, also did not neglect to use the period of inactivity to reorganize their defense-industrial base. Of particular relevance to the case of Ukraine is that the Germans had over-mobilized and needed to develop an effective system of exemptions for those in war-critical industries.

Training is thus a prerequisite to most other principles of war. As will be discussed, there must be sufficient training across branches so that the concentration of effort is effective on the tactical level. Initiative, likewise, is a virtue instilled only by training and most effective when made pervasive through it.

Initiative

Auftragstaktik, typically translated as “mission command,” is as much a method of training as a method of command. The idea of mission command is that orders are limited to instructing merely “what to do” but not “how to accomplish it” is straightforward. But merely issuing a regulation that orders are to be issued in this format would do little to recreate the flexibility that the German system of command offered its officers. It was extensive training in this method of command that created confidence in junior leadership to execute orders in accordance with their own judgment. Senior officers had confidence in their subordinates and junior officers had confidence in the backing of their superiors. This has particular relevance to Ukraine as it struggles with the legacy of the relatively centralized Soviet system of command. A culture of flexibility, initiative, and trust is developed only through extensive training. Superiority in this respect allows for rapid decision-making which offers the opportunity to disrupt the enemy and retain the initiative.

In 1940, this practice was crucial due to limitations in real-time communications and the rapid developments of mobile warfare. Mobile warfare still creates a rapidly changing situation, but modern communications technology and the use of drones for battlefield observation can allow more effective command and control. However, these cannot be used as a substitute for initiative and flexibility. Drones are shot down or malfunction and communications may be disrupted by electronic warfare. The ability of not only junior officers and NCOs but mere privates to take the initiative when necessary is irreplaceable.

“The moral is to the physical as three to one.”

- Napoleon Bonaparte

A culture of initiative is vital for morale—or rather, centralized command is corrosive to it. A networked officer using drones and the most modern communications available can be an invaluable resource to forces in contact, but they cannot be a substitute for an engrained spirit and practice of initiative. Initiative instills every echelon with the understanding that they are expected to seize opportunities as they are presented and cannot wait for authorization to do so. The case of France in 1940, as an extreme example of a command culture, left junior officers psychologically unable to arrange an operational level counterattack on their own initiative, even when the entire war hung in the balance. As Frieser writes, several times in which a French attack would have caught the Germans in a vulnerable position, officers with the authority received information too slowly while those that were informed felt that they were not authorized to take serious action.

By contrast, the German advance achieved such rapidity that its lead elements frequently had the chance to attack French forces while they were in staging areas and overran their headquarters. Despite inferior numbers and Panzers that in some cases could not even penetrate French tanks, the speed of the advance allowed the Germans to fall upon their enemies before they could get organized. Initiative was key to this achievement in that junior officers, by witnessing the state of the foes they encountered, understood the extent to which they had disrupted the enemy and chose to exploit further, even as higher echelons developed fears of a trap or overextension. The principle of initiative is that while officers on the scene may misjudge the situation with grave consequences, decisions of gravity must nevertheless be left with those with a first-hand knowledge of the situation. Lower grade officers must be trained and authorized to make these decisions based on their first-hand assessment of the situation.

Thus, to conduct a war of movement it is necessary that even the lowest echelons understand that they are not only authorized but responsible to make and seize opportunities as they are presented. Rapidity of action must be understood to be both the sword and shield of the force. This is a cultural dynamic as much as it is a doctrinal one. Junior officers must be trained to a sufficient standard that their superiors trust their judgment as the one on the scene.

Concentration

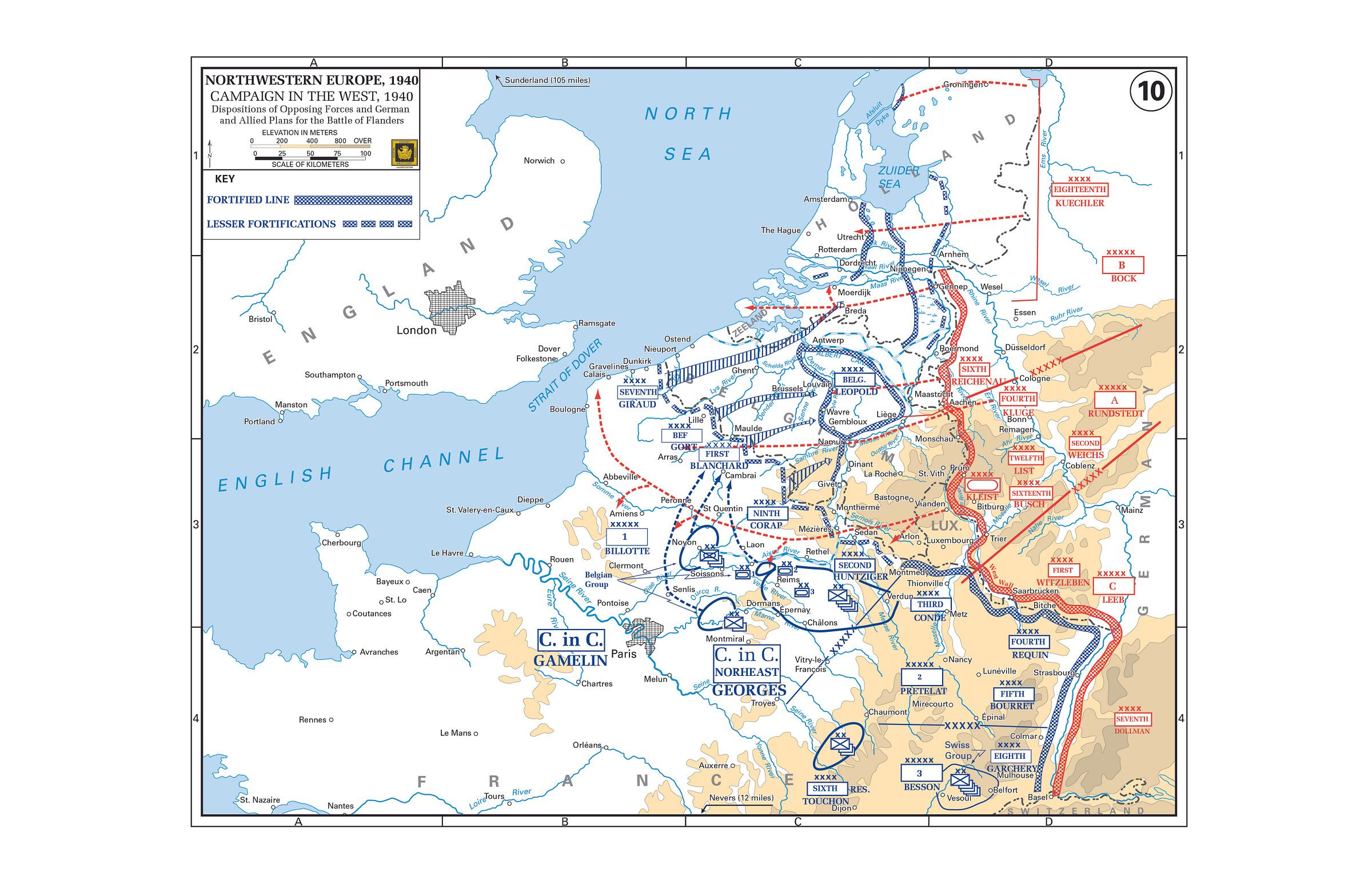

The antecedent of the principles of risk and deception is that of concentration. Achieving numerical superiority at the point of decision is the essence of operational art. German officers who were deeply familiar with Clausewitz undoubtedly recalled his assertions that “To all the advantages which the defender finds in the nature of his situation the assailant can only oppose superior numbers…” and that “…superiority in numbers is the most important factor in the result of an engagement… The direct consequence of this is that the greatest possible number of troops should be brought into action at the decisive point of the engagement.” That this was embraced in 1940 can be seen in the distribution of German forces. Army Group C, facing the Maginot Line had a mere 17 divisions. Army Group B, invading the Netherlands in the North had 29⅓ divisions. The focal point, Army Group A, was allocated 44⅓ divisions, including seven out of ten of the Panzer divisions.

The defenders have the opportunity to make all manner of preparations for the engagement, not only can they pick the terrain, but to also employ fortifications, a commonality between the French and Belgians in 1940 and the Russians today. Most important however, is that, as Clausewitz argues, every error the attacker makes is a gain for the defender. The attacker has to wrest things of importance from the defender, who has to merely fail to lose them. The defensive is the stronger form of war, and superiority in numbers is the primary means that can be employed to overcome its inherent advantages.

Ukraine, in seeking to expel Russia from the territory it has seized, must assume the role of the attacker and therefore embrace the principle of concentration. The threat of drones and artillery make this principle challenging to adhere to, but it is nonetheless indispensable. While new technologies may change the practice of war, they do not alter its nature. A superior concentration of manpower and firepower still represents the surest means for overcoming the inherent advantages of the defender. Western arms supplies and Ukrainian training should be oriented towards making such a concentration possible, not vainly seeking to achieve a breakthrough without one.

Deception

The Germany victory in the Battle of France stands principally as a victory for the concept of mechanized operations, but secondarily as a victory for military deception. While it was the accurate implementation of combined arms and mechanization that made the victory possible, it was deception that determined its magnitude.

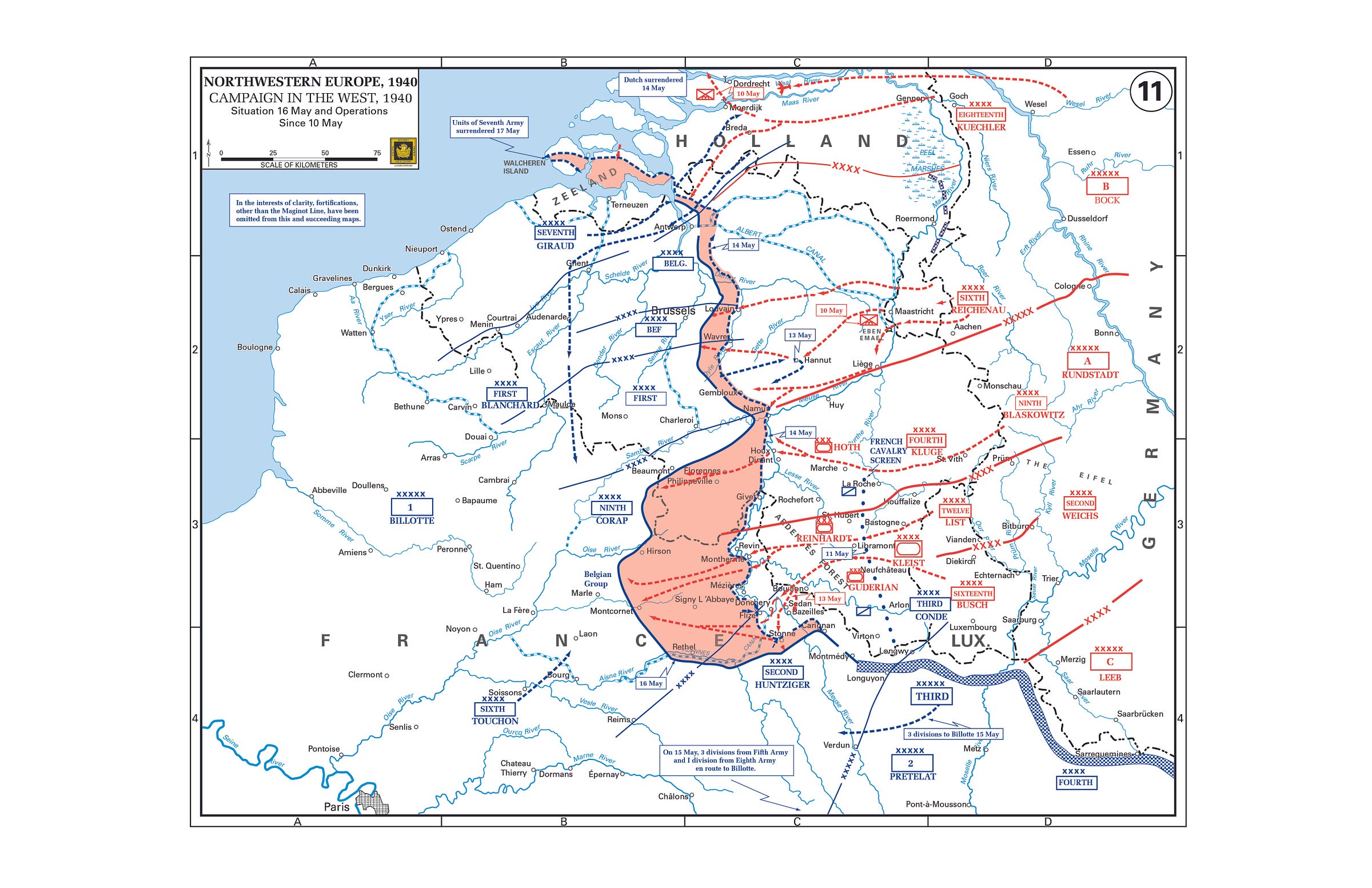

There were two main deception operations, each corresponding with an Army Group uninvolved in the Sickle-Cut. Army Group B, in the North, feigned a modern reenactment of the Schlieffen Plan, wheeling against the coast and making novel use of airborne troops to capture vital Dutch fortifications. German airpower was initially concentrated in this wing to further aid the deception operation and make it appear decisive.

This is the most famous aspect of the deception and led to the now infamous “Breda” addition to France’s Dyle Plan where, to meet the German main effort, the Allies would surge their best mobile units into the Netherlands. The Dyle Plan already called for the movement of Allied forces further North than the German main effort, but the Breda variant magnified the scale of the disaster. Had the forces committed to the Netherlands been retained as a strategic reserve, the German breakthrough may have been contained. As it was, these elite formations were pinned by Army Group B while Army Group A closed the trap on hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers.

Less famously, but perhaps no less decisive are the deceptions in the South under Army Group C. The weakest of Germany’s Army Groups, Army Group C faced the Maginot Line, the most extensive works of fortification of all time. Army Group C was tasked with engaging the garrisons of these forts so that they could not move North to counter Army Group A’s attack through the Ardennes and, before the offensive started, simulating the movement of Panzer divisions South as part of a purported effort to bypass the Maginot Line by invading Switzerland rather than Belgium. The fear of this led the French to overman the Maginot Line, leading the numerical inferior force of Army Group C pinning down a superior number of French divisions and allowing for local German numerical superiority at the decisive point. The Maginot Line, designed so that France would need to commit fewer troops to defend that frontier, completely failed as an economy of force operation.

As such, German deception operations contributed both to ensuring that French forces were either too far North or too far South to prevent the breakthrough in the Ardennes, and in ensuring that the bulk of Allied forces would be cut off by the drive to the Channel. Without these operations, France would have had a strategic reserve it could have utilized against the breakthrough or would have had fewer forces cut off in the Low Countries, giving it a better chance at further resistance or—at minimum—forcing Germany to pay a higher price in its eventual conquest. Success, therefore, is a product not only of one’s own abilities, but in goading one’s enemy into serious errors.

This principle is particularly relevant for modern operations. The lack of mechanization in armies in 1940 inherently limited the ability of an army to react to a breakthrough. For Ukraine to achieve and exploit a breakthrough, it is particularly reliant on ensuring Russian reserves are not prepared to contain it. This is particularly difficult due to the mass mechanization of armies and thus deception operations take on a renewed importance. Russian brigades will not be immobile as French divisions were in 1940. To fail to respond to a breakthrough, stratagems must be employed to ensure that they cannot.

A feint, such as that of Army Group B, is one example of how even mechanized formations can be kept away from the decisive point. Erroneous belief as to the direction of the main effort can prevent the containment of a breakthrough. As well, a fixing effort (such as that of Army Group C) may render forces immobile, ensuring that even if the decisive point is identified, the engaged formations are under too much pressure to withdraw towards it. Deception is thus the reciprocal principle of concentration; ensuring that the enemy fails to concentrate against the point of decision.

Risk

To introduce the strategic element of risk, there is no better term than “gambling.” Clausewitz associates military action more with chance than any other element of war. In 1940, circumstances conspired to make the German Army in many ways the arch-gamblers. Hitler, in his capacity as head of state and government had a personality and style of statesmanship that can best be characterized as that of an inveterate gambler. In 1938, his gambles paid off, against all odds, allowing Germany to annex Austria and Czechoslovakia. But in 1939, his luck ran out, and against his own will found himself at war not only with Poland, but the Allied powers at a time in which Germany was manifestly unprepared.

As Frieser demonstrates, the General Staff was aghast at the war that Hitler had blundered into. Its chief, Franz Halder, prepared a coup, even carrying a concealed pistol to meetings with Hitler. His plotting only ended when a misinterpretation of a statement by the nervous Commander in Chief von Brauchitsch led him to believe the conspiracy had been found out, causing him to destroy all evidence and ceasing contact with other members of the German resistance.

Despite the pessimism of the high command, Chief of Staff of Army Group A, Erich von Manstein, drafted a bold plan of operations, the now-famous Sickle-Cut through the Ardennes, aiming to trap the Allied armies in the Low Countries. Halder, still plotting against Hitler and attempting to dissuade an attack on France, buried this plan and had Manstein “promoted” to leadership of a corps that had yet to be constituted, in effect, making him irrelevant. Nevertheless, the plan had sufficient traction that it was brought to Hitler’s attention through informal channels, whereupon he approved of such an audacious gambit.

Halder himself, after abandoning his efforts to depose Hitler, came to accept many of Manstein’s ideas. Hitler and many of the more conservative elements of the high command did not fully embrace or understand the potential of deep penetrations of mechanized formations. Indeed, Hitler’s intention was explicitly never to encircle the Allied armies, as Manstein intended, but merely to gain the Channel coast and a favorable position from which to continue the war against the Allies—a gain understood in purely positional terms.

Nevertheless, whatever the extent of understanding or support of the Sickle-Cut, it was a rare instance of German operational plans being congruent with its strategic situation. With Germany’s naval and industrial weakness, it could not withstand a war of attrition against the Allied powers. It would be condemned to bleed and starve as it had done in the First World War. Manstein saw clearly that the only chance that Germany had was to risk everything on a bold operation in which victory would be sufficient to redress the strategic imbalance. To his detractors, this was nothing more than the return of the Schlieffen Plan. Yet, Manstein had contact with Heinz Guderian and other Panzer generals and was willing to bet on their ability to achieve decisive results in a war of movement.

By 1940, the die had been cast. Germany was at war and faced an unfavorable strategic situation. The Sickle-Cut concept was embraced because there was no alternative to a strategy of maximum risk. The magnitude of the German victory can only be understood in this context; there likely would have been a defeat of reciprocal magnitude had the operation failed, with Germany’s best divisions cut off in the Low Countries and annihilated by the Allies. Had Germany perceived itself in a situation of less desperation, a gambit of this nature may not have been attempted.

Of no lesser importance is the cultural circumstances in which the operation took place. The shadow of the failure of the Schlieffen Plan and the war of attrition and defeat that followed loomed large in the mind of the entire army, from senior leadership to the lowest infantryman. The animus of desperate aggression should not be underrated as a factor in the success of the German attack. Every man understood that the success or failure of the attack would decide the fate of his nation and that there would be no second chance. The Allies, in a superior strategic position and on the defensive, had no comparative desperation until the situation had deteriorated to a point beyond recovery, though this desperate courage helped in the defense of Dunkirk.

While this may correctly be understood as a historically unique occurrence (few nations go to war with the trauma of a failed offensive as central to their national psyche as the Schlieffen Plan was), there are nevertheless applicable principles. Ensuring that every member of an undertaking firmly and clearly understands its importance and the consequences of failure is applicable for all operations. This does not need to conflict with the goal of secrecy, as it is more a matter of the gravity expressed rather than the specific operational details that shape the moral environment.

Conclusion

Certain lessons from 1940 have clear applicability for Ukraine. The principle of training endures, particularly in view of the rapid expansion the Ukrainian armed forces have had to undergo in view of the invasion. The failed counteroffensive of 2023 and the delay in Western arms suppliers likely preclude an offensive in 2024. Thus, Ukraine should make virtue of necessity and seek to use the coming year to seek to out-reform the Russians so that it can take the offensive with qualitative superiority sufficient to achieve decisive results. Expanding both domestic and Western training programs should be at the core of this effort. Training engineers in particular should be emphasized due to the mines and fortifications Ukraine will have to overcome. Cross-branch training as well is a prerequisite for combined arms warfare.

Training also represents an opportunity to instill a culture of initiative, not only in officers but in NCOs, down to the lowest echelons. Drones and superior communications are vital tools that when used properly can confer significant advantages, but they are not a substitute for rapid judgment. It is inevitable that mistakes are made in war. Victory depends on exploiting them before they can be corrected. The necessary rapidity of action can be accomplished only with a mentality of initiative. For Ukraine to liberate its occupied territories, material rearmament will be insufficient; the culture of its armed forces must change.

In its prospective counteroffensive, Ukraine must embrace the operational principle of concentration. Even in an environment characterized by drones, mines, and fortifications, massing combat power along a narrow front is the only means by which to overcome the advantages of the defender. To successfully accomplish a breakthrough, this principle will need to be married to deception operations that will keep Russian forces away from the point of decision. Developing an operational plan that fulfills these criteria will be the task of the Ukrainian general staff, in collaboration with its allies and with intelligence services.

Finally, in this operational approach, Ukraine must accept a strategy of maximum risk. The principle of concentration that underwrites a breakthrough (as is required for mobile warfare) means putting all your chips on a single hand. Coming up short risks genuine military disaster. Yet, Ukraine needs a decisive victory. As has been demonstrated, Western aid is too vulnerable to electoral cycles to give Ukraine an attritional advantage over Russia. Even were it written in stone, Ukraine is at a demographic disadvantage such that bleeding the Russians white is simply not viable. As such, Ukraine must either consign itself purely to the strategic defensive and place the occupied territories beyond foreseeable hope of liberation or else embrace the strategy of maximum risk that is a prerequisite for mobile warfare.

Frieser concludes his book by referencing Marx’s quote, that history repeats itself, once as tragedy, the second time as farce. The first he corresponds to the Nazi victory over France in 1940, the second to the Battle of the Bulge in 1944, where a similar operational plan led to a resounding defeat for the Germans. Ukraine has no choice but to gamble if it wishes to regain its territorial integrity. Its success or failure will depend in part on the material support of the West but also its ability to gain a qualitative superiority on both the tactical and operational levels. As Frieser illustrates, the price of failure is high, but so too is the cost of failing to try. The uncertainty of Western arms supplies has left Ukraine like Germany in 1940: facing an unfavorable strategic situation and in need of an operational victory. To achieve it requires mastery of principles more than “game-changers.”

For further reading on German operational art, I recommend Robert Citino's The German Way of War and Gerhard P. Gross's The Myth and Reality of German Warfare (links to Amazon).