The Endurance of the Clausewitzian Principles of Strategy: A Retrospective on Ukraine's 2023 Counter-Offensive

Why the operational principles of concentration of force and effort continue to apply to the modern battlefield

In this post, I intend to explain why I believe the American operational plan was more theoretically sound and—with the benefits of retrospective—provide an explanation as to why the 2023 Ukrainian counteroffensive failed, based on publicly available information.1 2

"U.S. and Ukrainian officials sharply disagreed at times over strategy, tactics and timing… U.S. military officials were confident that a mass, mechanized frontal attack along one axis in the south of Ukraine would lead to a decisive breakthrough. Ukraine attacked along three axes, believing that would stretch Russian forces. Ukraine abandoned large, mechanized assaults when it suffered serious losses in the first days of the campaign.”

-The Washington Post

A charitable interpretation would compare the offensive with the broad front approach used by the Western Allies in the later stages of WWII. In this, they sought to overstretch the Germans, leading to decisive results as the overextended enemy allowed gaps to form during the fighting. In this case, the plan was stymied by successful Russian force generation efforts that gave it the reserves necessary to defend the wide front as well as by fortifications that provided economy of force.

However, even in this interpretation, the concept is flawed. The broad-front approach in WWII remains controversial but can be defended on the basis of the overwhelming superiority of the Allies in terms of both men and material. The Germans could not compete in quantity, so an operational approach designed to accent that effect had its justification. However, Ukraine, even assuming Russia continued to have personnel issues owing to a lack of mobilization, never possessed anything approaching numerical superiority.

Less charitably, the counteroffensive can be seen as a Ukrainian Kaiserschlacht, the German Spring offensive of 1918. General Ludendorff allegedly said, “I don’t want to hear anything about operations, we’ll just bash a hole and the rest will sort itself out.” Despite meeting initial tactical success, the German operation lacked a clear center of gravity and so foundered, taking only small amounts of indefensible territory at high costs. The failure of Ukraine’s offensive is nowhere near as significant, but it produced similarly only tactical results at a high cost.

Based on what we now know about Ukraine’s intentions, the reason for this is that two major operational principles were violated:

1. Concentration of Force

“Zaluzhny maintained more forces near Bakhmut than he did in the south, including the country’s most experienced units”

-The Washington Post

Ukraine refused to move from its general distribution of half its brigades in the north and half in the south. The reason for this was that Ukrainian command feared another attack on Kharkiv and felt it necessary to retain this posture. The failure to concentrate goes against all principles of operational thought. As Clausewitz tells us, "Defense is a stronger form of fighting than attack. To all the advantages which the defender finds in the nature of his situation the assailant can only oppose superior numbers…” Thus, the primary advantage of the attacker is the ability to choose where and when to strike, which provides the opportunity to concentrate forces and achieve local numerical superiority.

The principle of concentration is central to operational art but it is perhaps the most difficult to achieve. These may play a part in why Ukraine felt the need to eschew it. Concentration is difficult to achieve in secrecy, especially so in the age of satellite and drone reconnaissance. If a concentration is detected and opposed by a concentration by the defender, the attack no longer has numerical superiority and thus no advantage by which to overcome the innate power of the defense. As well, the forces concentrated must come from somewhere, which may mean dangerously denuding the frontlines in other areas.

In spite of these risks, there is no alternative to the principle of concentration. Without superiority of numbers and quantity of firepower, it is a fundamentally unequal struggle between the attacker and the defender. Even in cases where the courage or skill of the attacker can overcome the power of the defense, without numerical superiority, there will be no opportunity to exploit the success of the exhausted first echelon.

It is therefore clear why the violation of this principle was a central factor in the failure of the Ukrainian 2023 offensive. Ukraine achieved hard-fought tactical success that was ultimately inconsequential. A force must win the victory both with enough force that it can continue to attack and thereby obtain operational objectives and with sufficient rapidity that the defender has not had the chance to position reserves to contain the attack. Breaching a fortified line is never easy, but with sufficient concentration it may be quick, even if it is costly.

“The rehearsals gave the United States the opportunity to say at several points to the Ukrainians, ‘I know you really, really, really want to do this, but it’s not going to work,’ one former U.S. official said.”

-The Washington Post

Declaring the necessity of concentration is easy. Actually accomplishing it is much more difficult. For this purpose, field fortifications are invaluable, as they allow fewer soldiers to effectively defend a sector of front, permitting greater concentration elsewhere. Deception operations can be used to obfuscate the direction of attack. Feints and pinning attacks find their appropriate place here.

But even with these efforts, the principle of concentration is intertwined with the principle of risk. To attempt a breakthrough requires assuming a high level of risk. For example, had Ukraine concentrated its forces, it risked a Russian breakthrough in the north leading to a reoccupation of Kharkiv. Furthermore, even if the initial attack proved successful, the attacking force may have ended up itself cut off by a Russian counterattack, leading to its complete capture or annihilation.

It also risked a successful Russian air or drone attack on the massed forces. To protect against drones and air attack, air defense and air forces must also be concentrated. When an offensive is undertaken, every effort must be made to ensure that the point of concentration is the deadliest airspace on the planet. There is no sense in using Gepards and Patriot batteries to keep Kyiv safe while operational concentrations are destroyed by Russian airpower and drones. There is no target in the capital with value comparable with battlefield success on the operational level.

However, the advantages of the defender are sufficiently strong that there is no alternative to concentration. These are risks that need to be borne. If the risk of concentration is considered too high, then an army should not take the offensive. This may seem an extreme statement, however, the strength of the defensive form of war, particularly when the defender may utilize prepared positions, is such that it imposes a high barrier for entry for a chance at success. An attack without superiority of numbers means throwing troops into a fight where they have nothing with which to counter the inherent strengths of the defenders.

2. Concentration of effort.

The counteroffensive had three axes on which it attacked, but it had no designated main effort, its forces were dispersed. This is an innate problem in that an axiom of operations is that the decisive point must be the focal point of all effort. By overcoming the enemy in this spot, the follow-on forces may strike the flanks and rear of the enemy and create the conditions to force his general collapse. As it was, the success of each axis was purely local and could not aid the others, except indirectly. Nowhere did Ukraine constitute the kind of focused effort that could create an actual breach in the frontline.

The point of decision is not merely a matter of dogma. It goes back to the principles that Clausewitz describes as fundamental to war (such as friction) that make the defensive form of war stronger. As the offensive force enters into hostile country, it will necessarily be weakened by forces of attrition. Therefore, in order to achieve an operationally significant penetration, all available forces must be concentrated at the decisive point so as to maintain local superiority throughout the advance.

The famous phrase of Panzer general Heinz Guderian, proliferated through his own shameless self-promotion, is “Klotzen, nicht Kleckern,” typically rendered in English as “Strike with the fist, not with fingers spread.” More literally, it means “Hit, don’t spill.” The principle seems entirely obvious, yet when one looks at the dispersion of Ukraine’s directions of attack, it looks rather reminiscent of spread fingers or an attacking force that has been splattered into disparate parts.

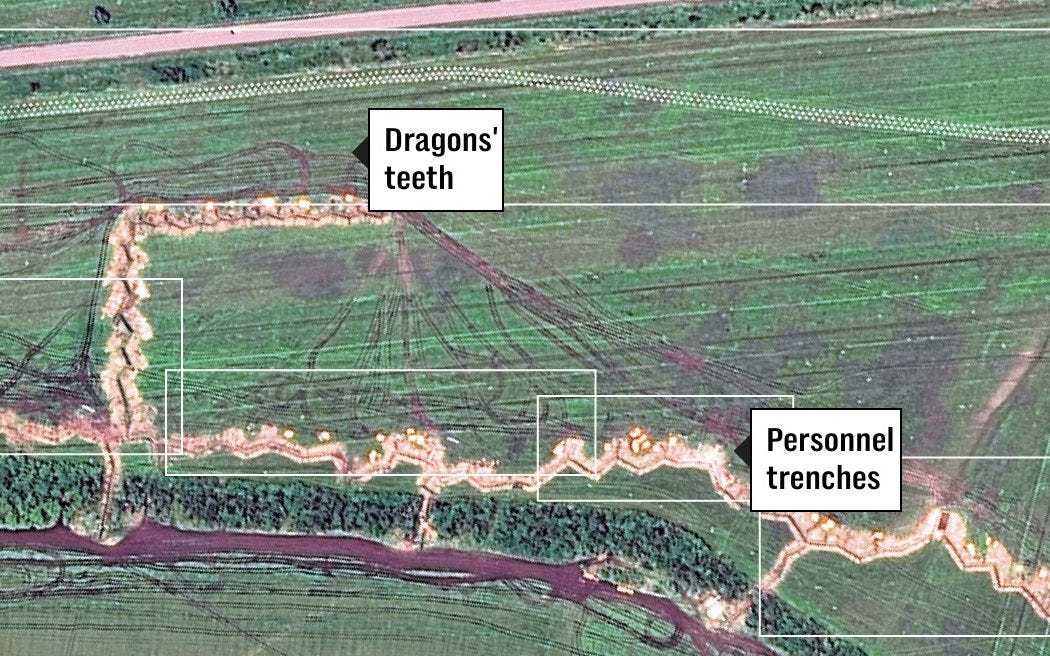

The dispersed approach was also particularly unsuitable for Ukraine’s circumstances. By spreading the effort across three axes, the attack needed to penetrate three times as much fortified frontline. Ukraine had a particular shortage of engineers, mine-removal vehicles, modern armored fighting vehicles, and air assets (including air defense). By splitting the attack, these shortages were felt all the more acutely. Had the attack followed operational principles and been concentrated in one particular sector, Ukraine would have had the opportunity to have absolute superiority, at least initially.

As it was, the high losses involved in an assault on a fortified line were severely consequential for each axis as crucial personnel or equipment were rendered ineffective without a replacement ready at hand. For instance, the loss of a single mine-clearing vehicle is a serious blow if it is the only vehicle assigned to an attack. If there are twenty allocated, the setback is much more easily overcome. That is not to say that is merely a matter of throwing bodies and equipment at the problem, but that even in the best-managed attack there will be some loss. War is not a movement against an inanimate object, but a true interaction. As such, acumen is not a replacement for redundancy.

In my initial assessment of Ukraine’s counteroffensive, I argued that a push in multiple directions was not necessarily incompatible with the principle of concentration. At the time, my interpretation was that the attacks in diverse directions were a fixing and deception operation in order to facilitate the decisive effort along one axis. However, as Ukraine did not concentrate its brigades in the south for the counteroffensive, it lacked the reserves to execute such a pinning attack as well as a concentrated thrust.

This interpretation was based on the assumption that Ukraine’s operational plan would be congruent with the basic principles of operational art, particularly given the American involvement then-presumed. However, as has now been reported, Ukrainian reasoning was based not on the usual standards of operations, but rather a judgment of enemy efficacy and morale. Ukraine judged that the Russians were in an incredibly poor state, as evidenced by the ease with which they had been driven away from Kharkiv. Had this assessment been correct, the broad front approach would have been justified. It required lower risks and offered higher rewards. If the Russian forces were beset by poor organization and morale, then pressure would send them reeling back, just as it had in 2022. If not, by avoiding concentration, there was no risk that the concentration would become nothing more than a target-rich environment for enemy firepower or become cut off in a failed attempt at exploitation. The ultimately illusory promise of this win-win scenario explains Ukraine’s rejection of American operational plans.

“It is somewhat likely that Russian forward lines could experience a precipitous collapse. The lack of professionalism and the shockingly inhuman conditions of the forward defenders make this a distinct possibility. Mutinous rumblings have been reported in other sectors, and it is not inconceivable that mass panic may spread in the face of persistent Ukrainian advances.”

-GIS Reports, October 25, 2023

The Necessity of Breakthrough

As Ukraine was facing an opponent that would not disintegrate under assault, it needed to achieve a breakthrough of a fortified line and it needed to exploit that breakthrough. This is a feat some have declared near-impossible in contemporary warfare, with many commentators declaring the “death of the tank” and an end to large scale mechanized maneuver warfare, arguing that the infantry, drone, and artillery-centric combat seen in Ukraine is the future of warfare. To declare a return of static and positional war on the basis of the stalemate in Ukraine is premature for a number of reasons, but an underrated factor is that it has always been much easier to defend than attack. The relative lack of movement in Ukraine is not because the combatants lack the conceptual framework for mobile, combined arms warfare or that technology has evolved to make that impossible, but because they lack the military systems to conduct it.

The stalemate seen in Ukraine is a consequence of the fact that the prerequisites for achieving an operational breakthrough are high. Neither combatant has had the chance to fully develop them. Russia has difficulties in combined arms operations due to low morale and endemic corruption at all levels of government. Most of its military problems were only revealed upon the start of the war, concealed through a culture of lies. Ukraine, meanwhile, was the poorest country in Europe at the time of the 2022 invasion, and was still struggling with corruption of its own. Since the invasion, Ukraine’s armed forces have rapidly swollen with reservists and conscripts and have been engaged in near-continual combat operations. As such, both belligerents have lacked the ability or opportunities to generate the sophisticated combat systems that allow an attacker to overcome the innate advantages of the defender. The difficulty is not in concept; it is in execution.

“Poor coordination with the adjacent sector left things unclear. We were ordered to begin our part of the operation only after the other sector had achieved something like ‘25 percent success,’ whatever that meant. Muddled messages, muddled minds. Was the observed desultory fire the beginning of the promised artillery ‘barrage’ or not? Radio security prevented clarification through direct communications.”

-Paul Schwennesen, GIS Reports3

It will be essential for Ukraine to develop these capabilities. The war it has fought thus far, of small-scale actions and raids, is incapable of inflicting the kind of defeat on Russia it needs. The disadvantages in industry and population that Ukraine faces mean it has to compensate through success on the battlefield. The breakthrough is vital to this because it is what transforms a victory from a mere gain of territory to something of operational significance. Through the concentration of effort at a specific point, the attacker may inflict such a defeat on the enemy that they are overwhelmed and not merely pushed back, but overrun. This idea of the breakthrough is why the principle of concentration is especially applicable to an attack on a fortified position.

Without overwhelming numerical superiority, a successful attack may do no more than drive the defender back to secondary positions (as many of Ukraine’s attacks during the counteroffensive did). From these secondary positions, the defender can contain the attacker, who is weakened by the assault on the initial position and operating now on unfamiliar footing, until reinforcements can be moved to counterattack. This often ends up driving the attacker out of their hard-fought positions, with comparable casualties on both sides.

By contrast, with numbers on the side of the attacker, a concentrated assault may sufficiently suppress the defenders to prevent their retreat to secondary positions without serious loss and so be able to actually breach the defensive line. It is this gap that can be used to obtain operational results through exploitation. Regardless of the risks of costs, without concentration, operationally significant results cannot be obtained.

Conclusion

While these criticisms can be made of the Ukrainian operational concept, that is not to say that their implementation would have necessarily created a success. In fact, had Ukraine gambled it all on a concentrated attack, it may well have suffered a far more crushing defeat than the ordinary defeat it in fact found. Concentration promises decisive results, but not necessarily ones favorable for the attacker. A massed attack that gets cut off or bogged down can mean disastrous losses with strategic consequences.

What’s more, airpower is an essential part of the combined arms that are required for a breakthrough and maintaining the momentum of the penetrating force. This is all the more the case when confronting fortifications, where bunkers, trench lines, and artillery need to be suppressed so that engineers can work. Thus, it is entirely possible that without the ability to gain local air superiority the Ukrainian counteroffensive could never have been successful. In that case, however, the counteroffensive should never have been attempted.

These operational principles mean that to conduct an offensive means assuming the highest risk. To follow them is to court disaster, but the alternative is mere waste in attacks that cannot achieve significant results. Without concentration both of mass and effort the attacker cannot expect to overcome the innate power of the defense.

At the center of the question of Ukraine’s strategy is the status and durability of Western aid. If it is forthcoming, extensive, and durable, Ukraine has a clear strategic advantage, being only inferior to Russia in raw manpower. So long as the West is willing to provide it and Russia cannot win a decisive victory, Ukraine will have an advantage in an attritional struggle. Western aid will be able to ensure it has more modern equipment operated by better-trained personnel. In this situation, Ukraine has no need to gamble on a decisive battle but can pursue a strategy of exhaustion, something considered both by Clausewitz and later by Hans Delbrück as an equivalent form of war.

However, it is extremely unlikely that aid will be structured to provide this certainty. The panoply of democracies that constitute Ukraine’s backers are subject to the vacillations of elections and party politics. At any point, developments outside the control of Ukraine can result in a sudden end to material support. This has already been seen in both the US and EU, where limited dissenters have succeeded in blocking or delaying it. But even were there no question of the durability of aid, a strategy of exhaustion is politically unpalatable in Ukraine. This is understandable, considering it means leaving the occupied portions of the country to endure the abuse of the Russians for longer than strictly necessary.

As such, unless there is firm consensus on a strategy of attrition, aid to Ukraine should be focused on developing the capabilities to create and exploit a breakthrough rather than to attrit the Russians generally. What’s more, Ukraine’s leadership must accept the attendant risk of disaster that it means and embrace the principles of concentration of force and effort in future operations.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/12/04/ukraine-counteroffensive-us-planning-russia-war/

https://www.reuters.com/graphics/UKRAINE-CRISIS/MAPS/klvygwawavg/#four-factors-that-stalled-ukraines-counteroffensive

https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/assessing-ukraine-counteroffensive/

It sounds like it was too risky to have made a counter attack at all, but also that it would be politically unfeasible to continue to attempt to attrit. It's an impossible situation that they might have actually found the best result for. Unless their casualties were unacceptably high from the failed attack?