Building a MAD World: Mutually Assured Destruction as Nuclear Strategy

How much security can nuclear weapons actually bring to the table?

If Mutually Assured Destruction is a fact, why do nuclear powers feel threatened by each other? What does it matter whether the Soviets base missiles in Cuba, or Ukraine joins NATO, if any kind of war would have the same outcome of total annihilation?

In the previous article in this series on nuclear strategy, we discussed the strategy of Nuclear Superiority–how and why states attempt to win nuclear wars and escape from MAD. In this article, we talk about how living in the shadow of MAD affects the behavior of states and the role of nuclear weapons as the “ultimate deterrent.” In particular, why we still see arms races and intense security competition between states that—according to the theory of MAD—have their survival assured.

The Strategy of Pure MAD

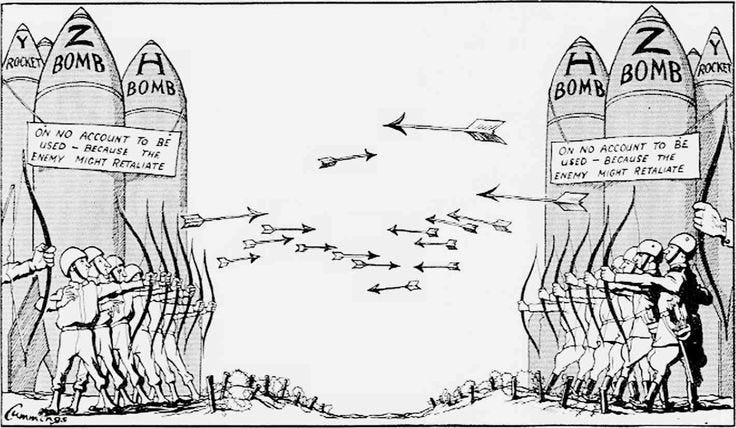

The strategy of relying purely on MAD has never been implemented. It is nevertheless worthy of discussion because it seems to be the logical conclusion of nuclear arms and there has been extensive argumentation that the failure to utilize such a strategy has been a policy failure. In the strategy of Pure MAD, the basic assumption is that the consequences of nuclear war are too horrifying to be risked, so confrontation between nuclear powers is simply out of the question. Trying to achieve nuclear superiority is pointless and a waste of time and money. Conventional wars between nuclear powers are a relic of the pre-nuclear era, and the maintenance of large conventional forces is simply a waste. Both sides are aware that any conflict would be suicidal, so entertaining the prospect of any war between them is nothing more than fantasy.

From this perspective, the intense security competition of the Cold War, all the arms races and crises, was ultimately pointless and based on a failure to recognize the reality that nuclear war was never going to happen. It would have made no difference if the Soviets had placed nukes in Cuba—they might as well have placed one in Washington DC—there was no advantage that they could have gained that would have made war anything other than mutual suicide.

If the arms races are pointless, however, then how many nuclear weapons does a country need before MAD takes effect? One device is certainly too few, considering the possibility of its destruction, interception, or failure. Even a dozen would still suffer attrition from these problems, meaning that in a war, your opponent would risk the annihilation of a few cities in exchange for totally destroying your country. Is that Mutually Assured Destruction? Did the US only need to be able to bomb Leningrad or the Soviets, New York, for deterrence to hold? Opinions differ on exactly what the highest acceptable rate of losses is, which provides an incentive for countries to build arsenals capable of threatening total destruction.

The country that has adhered closest to the strategy of Pure MAD is the People’s Republic of China. Throughout the Cold War, China refused to engage in the nuclear arms races that characterized competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. While the Soviet Union and United States stockpiled tens of thousands of warheads, China instead maintained only a couple hundred. However, it is notable that China, as it takes an increasingly aggressive policy towards Taiwan and the United States, has taken steps to expand and modernize its nuclear arsenal. Evidently Chinese policy has lost its faith that a small arsenal is sufficient to achieve MAD.

Critics of the strategy of Pure MAD may also point to the fact that it relies on the rationality of states. It’s not possible to deter an irrational opponent, even when the stakes are the deaths of millions. However, its defenders can point out that “not suicidal” is a low bar for rationality. This is particularly the case on the national level, where nuclear use requires several points of agreement and a long chain of compliance that makes individual insanity leading to nuclear annihilation unbelievable.

The “Stability-Instability” Paradox

However, the assumption that in a MAD world nuclear weapons will never be used creates a problem of its own. What’s known as the Stability-Instability Paradox, describes the situation, in that there’s such stability on the nuclear level (they’re not going to be used) that there’s instability at the conventional level. Essentially, nuclear powers feel comfortable fighting conventional wars against each other because they know it’s impossible for it to escalate to the nuclear level. Any state would prefer to be defeated conventionally than to suffer the total devastation of a nuclear exchange.

In some ways, this can be seen as an extension of the previously discussed principle of salami slicing tactics as a counter to the doctrine of Massive Retaliation. Just as you wouldn’t want to fight a nuclear war—even one you expected to win—over a minor question, there are practically no circumstances in which you would initiate a nuclear exchange with the knowledge that total annihilation would be the inevitable result. Just as proxy wars and covert actions are safe to execute against a doctrine of Massive Retaliation, all actions up to and including conventional, shooting, war are safe to execute in an environment of Mutually Assured Destruction. So long as the worst outcome possible for your opponent is preferable to a nuclear exchange, threats of nuclear use are empty. And there are very few cases in which losing a conventional war is remotely comparable to starting a nuclear one.

In the classic analogy of an Old West gunfight, MAD means a situation in which even if you shoot me before I can get a shot off, I can still shoot you before your bullet reaches me (or at least, before I die). In the strategy of Pure MAD, I no longer have to consider you a threat in these circumstances, because we both know that a duel could only end with us both dead. As a result, it would be a mistake for me to invest in a better gun, or to spend time and energy working on my quick-draw—there’s no advantage I can get that will stop me from dying if it comes to a duel. The stability-instability paradox can be represented by the fact that you and I might get into a bar fight because we’re not worried it’ll escalate to a duel.

Theory Meets Practice

The stability-instability paradox had particular relevance for the United States during the Cold War due to its commitments under NATO. The balance of conventional military forces in Europe favored the Soviet Union through most of the Cold War. Deterrence in Europe consequently depended on the threat of nuclear war. As a result, the prospect of MAD providing stability on the nuclear level threatened to cripple NATO’s ability to deter a Soviet conquest of Western Europe.

However, NATO’s European members clearly saw that the willingness of the United States to start a nuclear war over the fate of Europe was doubtful. While it was certainly possible that the US would be willing to risk the consequences of nuclear war to prevent Soviet domination of Europe, that there remained a question around it elevated the risk of war. If the Europeans weren’t confident in American guarantees, the Soviets might make a similar assessment and call the bluff.1

There were two obvious solutions to the problem of extending the nuclear umbrella. The first was nuclear proliferation within NATO. If all the Western European countries of the alliance had nuclear arsenals of their own, the Soviets would not doubt that they would use them in self-defense. However, the United States strongly opposed further proliferation explicitly on the basis that it increased the risk of nuclear war. To this end, it proved willing to weaken its deterrent posture in Europe (by forgoing the ultimate deterrent) in order to control the risk of escalation.

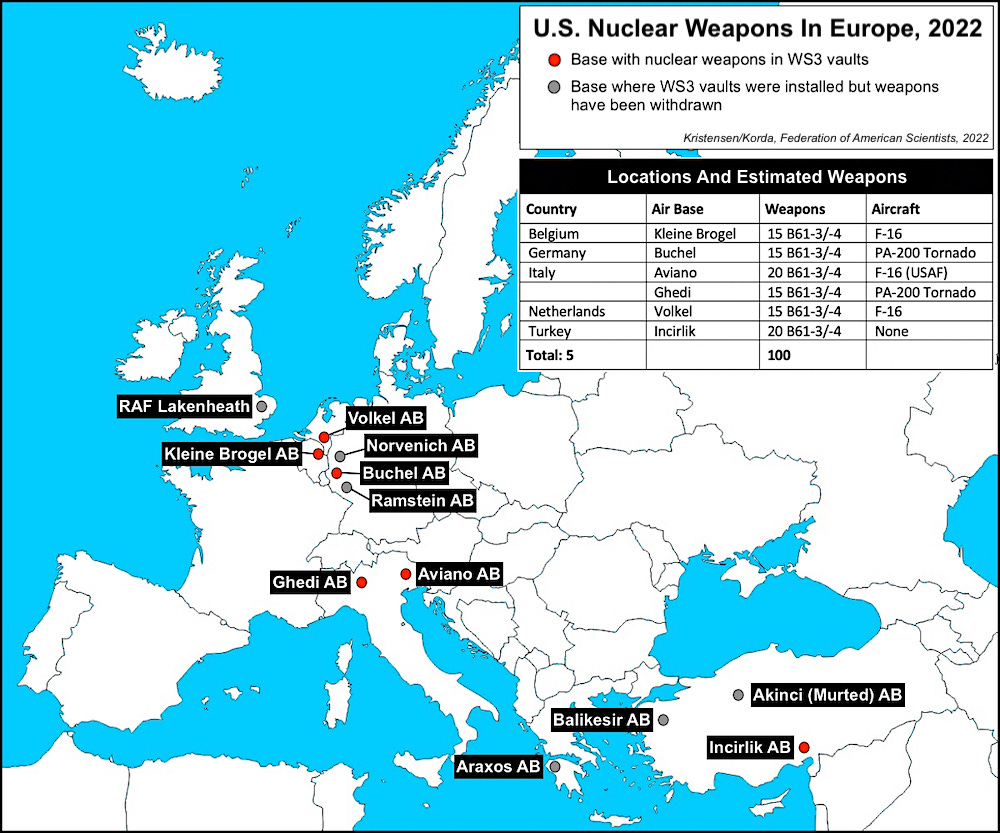

The alternative was nuclear sharing. The US could base nuclear weapons in allied countries and so increase the likelihood that they might be used in a crisis involving NATO. It is into this niche that tactical nuclear weapons were envisioned. By developing nuclear bombs intended for battlefield use, it sent a clear signal to the Soviets that it could not hope to win a conventional war in Europe; should a war break out and things appear to be going well for the Soviet Union, it would soon find the Red Army devastated by nuclear attack.

Nuclear sharing could therefore to some extent allay fears that Europe was vulnerable to conventional attack, however, it left open the very thorny issue as to where launch authority rested. While nuclear weapons might be based in a country, operational control remained in American hands. The Americans proved unwilling to devolve control over nuclear weapons for the same reason that they opposed nuclear proliferation: more fingers on the trigger was understood to mean greater danger of nuclear war.

The idea of nuclear sharing was nevertheless explored through proposals of creating a “Multilateral Force” (MLF) to have operational control. This effort failed because launching through the MLF still required American approval, leaving in place the danger that the Americans might abandon Europe, and because it at the same time in no way restricted the United States from using its strategic arsenal in a crisis. In other words, MLF provided neither a trigger nor a latch, and so was abandoned. Tactical nuclear weapons were nevertheless pursued and deployed to Europe during the Cold War.

While nuclear sharing without launch authority did not fully address the concerns of Europe’s non-nuclear states, it was nevertheless considered an essential step in linking conventional war with MAD. This may be seen as an effort to avoid the stability-instability paradox, where MAD causes nuclear weapons to lose their deterrent value. Tactical nuclear weapons do not inherently cause all-out nuclear war, but have a danger of doing so-its the clear next step. So threats of their use in a conventional war are credible, and therefore so is the danger of all-out nuclear war.

An Artificially MAD World

The historical record therefore demonstrates that MAD was not seen as automatic or stable. Even if nuclear arms have caused a revolution in international relations, states nevertheless cannot rely solely on nuclear arms for their survival or the defense of their vital interests. The strategy of Pure MAD is not viable because it is not automatically assured. If the United States had had an arsenal as small as China’s during the Cold War, the Soviet Union may have considered itself secure enough to attempt a conventional war in Europe, knowing that the Americans could not threaten nuclear escalation unless they were suicidal.

Without an effort, nuclear weapons do not automatically preclude war between the great powers. As such, intense security competition between them is an expected and rational outcome. The Cold War and its arms races can be seen not as the product of a frenzy of irrational hysteria but a response to the real danger of deterrence failing. More destructive weapons in ever greater quantities were sought not in ignorance or disregard for the consequences, but as a means to make those consequences unquestionably clear and, in so doing, preserve peace.

See J. Michael Legge, Theater Nuclear Weapons and the NATO Strategy of Flexible Response (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1983).