Has Russia Mobilized? Not Yet.

Men are drafted, but Putin resists mobilizing Russian society for war. Why does it matter? And what does it tell us?

The Ukrainian people, the state, and its military are fully and irrevocably engaged in struggle in the face of the Russian invasion. The Russian state is engaged, the Russian military as well, but where-oh where-are the Russian people in this conflict?

The draft notices have arrived, and men of military age stream across the borders, but Russia has not, in fact, mobilized. Despite the fact that mobilization is and was the single factor most likely to deliver a Russian victory, a mobilization has been meticulously avoided. Current measures have been termed a “partial” mobilization as part of this effort, with Russian propaganda seeking to emphasize its limitations and exclusions. Despite the fact that Russia is undoubtedly waging a war against Ukraine, the Putin regime, far from inciting the Russian people with patriotic fervor to fight and win a war, has made considerable effort to enforce the minimizing term of “special military operation.” In this article, I will seek to answer the question as to why this is militarily detrimental and why Putin has nonetheless persisted in this course.

#Don’tPanic, a Kremlin backed campaign to allay fears regarding partial mobilization

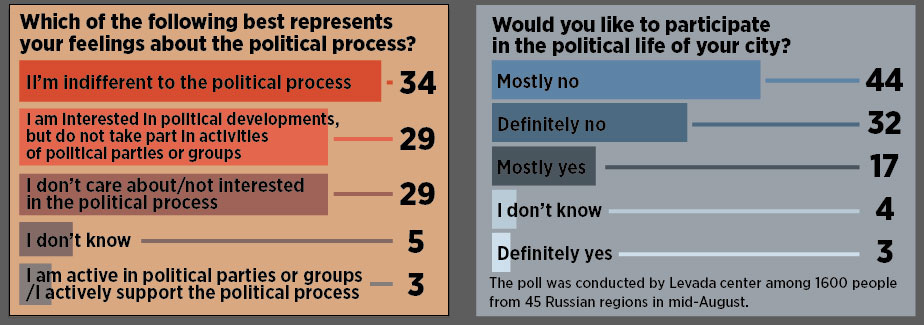

Regardless of his intentions, the so-called “partial mobilization” is indicative of the fact that Putin’s “special military operation” has reached the people. However, there is no corresponding effort to engage the Russian people in the struggle. Men are being pressed into service, but Russian morale stands at its lowest ebb.The mobilization of the people does not necessarily involve mobilization in the sense of conscription, but it consists of a political effort to make a conflict a matter of public interest and patriotic duty. This creates a national environment in which people flock to the colors, eager to fulfill their patriotic duty, rather than race to third countries to avoid service.

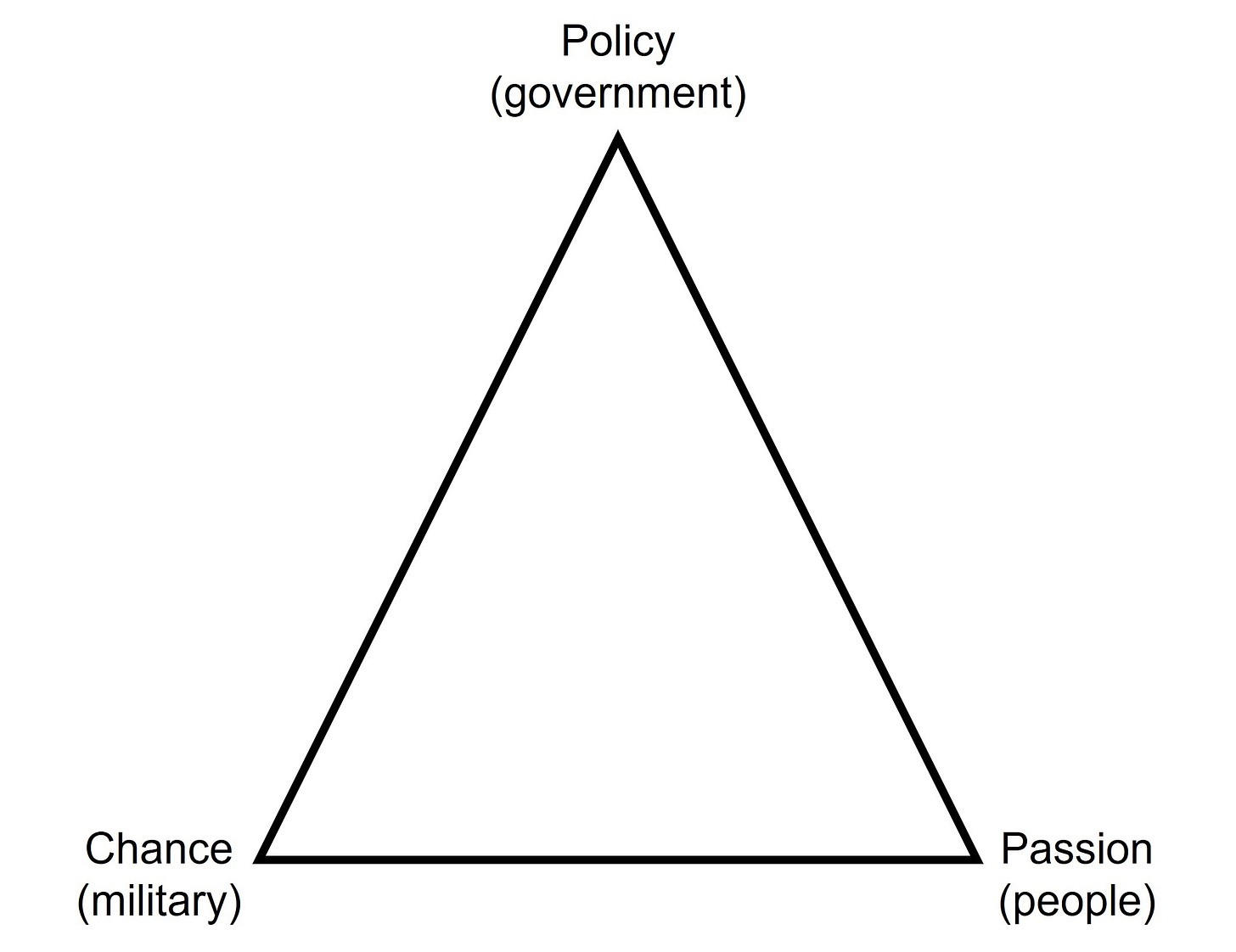

To illustrate the theoretical underpinning of the morale problem, I will turn to Carl von Clausewitz’s concept of a trinity of forces that drive war. Clausewitz’s trinity of passion, reason, and chance, produces his secondary trinity of the people, the state, and the army respectively.

The Ukrainian people, the state, and its military are fully and irrevocably engaged in struggle in the face of the Russian invasion. The Russian state is engaged, the Russian military as well, but where-oh where-are the Russian people in this conflict? Most states have a large capacity to drum up popular support for foreign interventions if they are willing to expend the political capital. Russia has refrained from doing so, and as a result, finds itself at a dramatic morale disadvantage. Russia is relearning the lessons that the powers of Europe learnt after their defeat at the hands of Napoleon: a mercenary army is far less effective than a national army. The leveé en masse is not effective without the engagement of the popular will.

This brings us to a central thesis of Clausewitz, that the form of war is derived from the structure of the society waging it. The monarchies of the eighteenth-century could not call upon the people and were forced to fight cabinet wars with armies drawn from the dregs of society. It was only with the co-option of nationalism by the state that involvement of the people brought a critical level of passion to war that overwhelmed armies based on mercenary institutions.

In his effort to keep the war in Ukraine distant from the Russian people, Putin has hobbled his warfighting capabilities with the same deficiencies of armies during the “cabinet wars” until and unless there is a transformation in the relationship between the people and the state. The Russian army is not quite the mix of foreigners, prisoners, and the impoverished that armies of the eighteenth century were, but it is also not far off. Even with the introduction of conscripts, the Russian army remains primarily a force of those who could not avoid service and, as a result, fights like one.

The military advantages of popular mobilization are undoubtedly clear to Putin, which thus presents the challenge of explaining the decision to avoid doing so. To this end, we may turn to Clausewitz’s famous assertion of the unity between war and politics. That Putin has not attempted mobilization indicates that he has judged the risks of mobilization to be greater than those he runs by continuing the war in Ukraine without it. As we have established, mobilization is the single factor most likely to prove decisive in preventing a Russian defeat. Why then has Putin avoided this measure?

Putin has in many ways limited his political capital by expending it in depoliticizing the Russian people. To greatly simplify the relationship between the Putin regime and the Russian people: corruption and a low quality of life are accepted in exchange for an end to Russia’s international humiliation of the Yeltsin era and governmental non-intervention in personal affairs. The line endlessly repeated by Russian propagandists is that Russia is corrupt, but all institutions are, and surely Russia was less corrupt than the western hypocrites that had abandoned traditional values and feigned propriety. A combination of a thought-terminating cliche and an appeal to base national chauvinism. The tactic is effective, even when transplanted outside of Russia, in promoting apathy. Most important for Putin, apathy proved a potent recipe in avoiding large scale opposition to the regime from developing.

Drawing by Alena Repkina, Originally Appearing in RUSSIA BEYOND

Apathy, however, is far from the optimal ground from which to launch an invasion. A depoliticized public might give the regime safety from popular movements, but no one is storming trenches in the name of apathy. This absence of morale has been the critical inequality enabling the rapid offensives of the Ukrainian army. Only a politicized people can call forth the popular mobilization needed to wage modern war.

To call upon the people represents a risky prospect for a regime maintained by the promise of non-interference in exchange for apathy. A motivated populace is likely to ask the regime uncomfortable questions regarding the course of the war in Ukraine. By keeping the public apathetic and depoliticized, the course of the war in Ukraine becomes less relevant, and the falsehoods of state media easier to blithely accept. Just as mil-bloggers and supporters of war in Ukraine have begun to accuse Putin of its mishandling, a Russian people roused to national fervor are unlikely to look kindly on the architects of national humiliation.

These nationalists and imperialist nostalgists were happy to lie in bed with the regime while it made a show of projecting power and to make excuses for its failures when war was “hybrid” and through a television screen. But failure on Russia’s doorstep is an unacceptable violation of the compact. It’s unnecessary to refer to Russian history, even to the extent of Yeltsin, when the more simple answer is that no one likes their country humiliated, least of all nationalists. Putin’s graft was tolerated when he seemed to earn the respect and fear of the world. With each battlefield failure, it becomes less likely to be overlooked.

Indeed, the compact between state and people in Russia is to not look too closely at the reasons a supposed superpower has an economy smaller than Italy and a GDP per capita on par with that of Argentina. A politically potent popular nationalism would demand a national strength that Putin’s kleptocracy lacks the institutions to deliver. Mobilization, therefore, while it would be militarily beneficial, would destabilize the Russian political order. The critique from nationalist and milblogger circles has been noticed by Putin and is likely viewed as demonstrative of the consequences should the nation take interest in the war.

Based on Putin’s actions, it appears that he views defeat in Ukraine as far from the existential threat he claims. Putin believes that his regime can survive a defeat in Ukraine so long as the depoliticized order holds. While Russia runs a greater risk of defeat in Ukraine by refusing to mobilize, Putin believes that increasing his likelihood of victory in Ukraine via mobilization would also increase the likelihood of his being overthrown. Let us not forget that war is a political act. The political prize of victory in Ukraine is worth only so much to Putin and so far not enough to politicize the Russian people to attain it. Whatever victory in Ukraine is worth, it seems regime security is worth more still.

It is clear from the Russian political landscape why Putin has refrained from popular mobilization. It is also clear from Clausewitzian analysis why anything less is unlikely to deliver success. Where does that leave us in terms of outcomes? At the moment, Putin’s most serious challenge comes from his right flank. This is a threat he appears to be cognizant of, but he has little choice other than to run this risk if he hopes to win the war in Ukraine. If Putin chooses to continue to escalate rather than attempt to weather a defeat in Ukraine this faction will increase in influence.

This leads to the less than encouraging conclusion for the free world, that any fall of Putin’s regime will be the work of a right wing unsatisfied with his performance and unrepentant in its imperialism. Yet, it would be a mistake to make too much of the avenue from which the most serious threat to the regime resides. The interests that topple the old regime merely begin the power struggle from which they have no guarantee of emerging victorious. The source of the collapse may come from one quarter, but which party emerges with the power of state cannot be assumed on that basis.

While this article has focused on Russian calculus, it must be remembered that the balance of force on the battlefield is likely to continue to move in Ukraine’s favor. The vital economic support, materiel, and intelligence provided by the west are key factors in this process. However, none are more decisive than the fact that the Russian people are not engaged in this conflict, while the Ukrainian people are committed to victory. Unless Putin escalates to social mobilization, and chooses to risk his regime on that, Ukraine will possess an indelible morale advantage.

I wonder what additional strength a full mobilization could unlock.

Drafting more men gives diminishing returns if they have to be armed with increasingly old weapons. The Russian system seems challenged to sufficiently train the professional army, let alone many draftees. Switching to war economy only makes sense if the freed civilian resources can be applied in a useful way for military production or logistics. While this was the case during WW2, I find this not obvious now. Mobilizing civilian logistics capacities and switching the civilian industry to produce simple arms or other gear (tents, clothes, fortification materials) is possible and useful, but I am not convinced that civilian resources can be used to increase high tech arms production significantly. Not because of a principal impossibility, but because Russian advanced technology industry is so weak outside of the arms and nuclear sector. In other words, almost everyone and everything that could in theory be used to produce advanced weapons already did so prior to the war in Russia (very different from say China or Germany, which have a strong advanced technology sector outside of military needs).