The Axis of Disruption - Why States Seek Destabilization

The Challenge of Interdictionist Powers in the 21st Century

What drives the actions of countries on the world stage? The discipline of international relations has languished on this question since its inception. Various explanations have been put forward, including the constructed norms of the international system, the anarchy of interstate relations, and human nature. Of the myriad of explanations proposed, this article will focus on the role of both domestic politics and the position of states in the international order to explain why states take actions that seem counter to their national interest.

There are two common approaches to viewing the question of how domestic politics impacts the behavior of states. The first is the “black box” approach. In this view, common among Realists, domestic politics is not relevant to the behavior of a country on the world stage. The international order is anarchic and therefore so dangerous that states are forced to act in the interest of their survival, regardless of their domestic political configuration. From this point of view, dictatorships and democracies will act the same way if faced with the same situation.

The second approach recognizes a distinction between kinds of states but abstracts this difference into a dichotomy. The most common is that of “status quo” powers and “revisionist” powers. The former are those driven more by fear of losing power, whereas the latter are driven more by desire to gain power. Status quo powers are the “winners” of the current international order. The United States and its allies are the status quo powers of the day. This does not mean that they do not desire change, but that they have written the rules of the international order and are more interested in defending them than upending them.

Revisionist powers are so named because they aim to “revise” the international order in their favor. Aggressive states are traditionally characterized as revisionist powers. Revisionists invade their neighbors to conquer or colonize them to increase their own power. They do this not just for its own sake, but because they ultimately seek to win a great power war against the status quo powers. Through this war, they intend to impose their own order, which they would then defend as status quo powers.

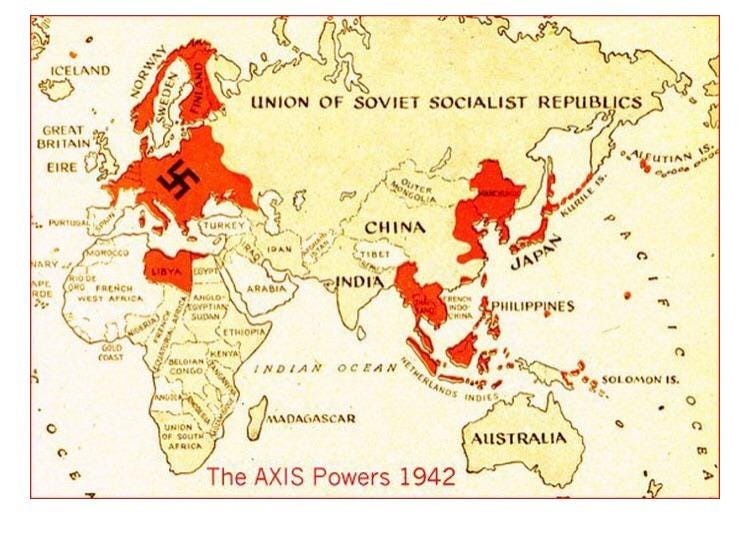

The Axis powers of WWII are considered archetypal revisionist powers. These states were profoundly dissatisfied with their positions in the international order and resented Anglo-French hegemony that had been formalized at the end of the First World War. Fascist Italy invaded Ethiopia, while Germany preyed upon Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland in turn. Japan colonized Manchuria and sought to subjugate China. What distinguished these actions from an ordinary landgrab was that they were part of a grand strategy to assemble (by conquest) the power needed to challenge and defeat the reigning powers.

This was why Germany was willing to risk war with France and Britain by first violating the Munich Agreement and then invading Poland: war with the Western powers was the inevitable goal of the revisionist agenda. This was also why the strategy of appeasement was doomed to fail, both from Chamberlain at Munich and the Soviets with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The Germans aimed at hegemonic status, making war unavoidable by means of concessions, unless the French, British, and Soviets were all willing to accept German domination of Europe uncontested. It was vain to hope that Germany could be satisfied with limited territorial gains as this territorial expansion was driven by the ultimate aim of gaining strength with which to confront the status quo powers.

Yet, there are states that do not seem to fit in either of these categories. For example, Russia and Iran, avowed opponents of the American system, cannot be said to be revisionist powers for the simple reason that they are too weak to even consider fighting a great power war against the United States and its allies. To illustrate the disparity in power, there are three US states that each have a larger economy than the entirety of Russia. As a result, Iran and Russia are far more focused on deterring American efforts at regime change directed against them than they are on considering initiating a war aimed at breaking American hegemony.

For this reason, I believe the traditional dichotomy between revisionist and status quo powers is insufficient. These countries and powers like them are ultimately not focused on attempting to rewrite the rules of the international order but instead on disrupting or destabilizing it. As such, I believe that they deserve the label, rather than revisionist, of “interdictionist” powers. They oppose and seek to prevent the functioning of the existing system but are not attempting to implement an alternative order and as such behave in a fundamentally different manner.

It’s certain that these states would rewrite the international order if given the chance, but the difference between desiring something and actually pursuing it is the difference between reality and mere intellectual play. What the world would look like if Russia or Iran could write the rules is an interesting thought experiment, but nothing more. The interdictionist powers are aware that they do not have the requisite power needed to pursue a revisionist agenda in earnest. They may, in an abstract sense, aim to secure enough power to one day be in a position to rewrite the rules, yet the grand strategy of these states does not involve a great power war to actually achieve these goals. Rather, the focus is on weakening the hegemonic powers and hastening its supposedly inevitable collapse. There is no master plan for the downfall of current order, merely an intention to oppose and disrupt it wherever possible.

A central question is why states become interdictionist rather than revisionist or status quo powers. Particularly in the liberal world order promulgated by the United States following the Cold War, there are significant incentives for bandwagoning. A key case in this is that of China. China is a noted example of a country that chose to accept at least partially the conditions of integration into the Western system and reaped the power benefits of it through massive economic expansion. However, as its internal politics turn increasingly towards chauvinist nationalism, the acceptance of participation in the liberal order is being brought into question. China's belligerence has already had consequences as the West seeks to limit its exposure through protectionist means. Yet China has already secured enough power through its participation in the liberal system so as to constitute a revisionist power. China is contemplating a great power war against the United States over the island of Taiwan and sovereignty over the South China Sea.

Yet, the disconnection of China from the international system threatens to stifle its revisionist aspirations. China has not yet overtaken the United States and its allies in terms of power or by most measures of economic might. Its belligerent behavior has imperiled its rise economically and alienated potential partners that might otherwise have been interested in revising the international system to shift power away from the United States. As such, the behavior of China has increasingly come to be reminiscent of that of interdictionist powers. In China’s case, its diplomats have been adhering to a policy of overt chauvinist nationalism for domestic consumption. If we look at the bona fide interdictionist states, we see a parallel pattern of domestic politics driving a belligerent foreign policy.

Iran and Russia are governed by regimes that gain their legitimacy through opposition to the American-backed liberal democratic world order. This is important in that it allows for understanding the actions of these powers through a lens not of power politics, but as part of a policy of regime security. Iran or Russia could drastically increase their share of power in the world by joining the liberal democratic order. Their political isolation has led to economic isolation and a continued failure to keep up with the growth of countries that are willing to integrate into the liberal system. But doing so would involve changes to their governing structure that would be unacceptable from the perspective of regime security.

From this standpoint, it is necessary to look closely at the domestic politics of the states in question and set aside the “black box” approach common in international relations. Critics of US foreign policy towards these states often look to the intense focus on regime security on the part of Iran and Russia and conclude that better relations are possible were the US only to make clear and offer assurances that it had no intention of fostering or assisting efforts at regime change. However, these efforts are misguided. These regimes oppose the United States and its allies not just because they fear hostile action, but because they fear organic internal action. They maintain their popular support through opposition to the liberal world order. In so doing they create a siege mentality that justifies their authoritarianism. The opposition to so much of the world which is so detrimental in terms of power and prosperity strengthens the regime through the reinforcement of the friend-enemy dichotomy. There is no time or space for dissent and criticism of one’s own government when the world is arrayed against you. As such, there are no assurances that the US can offer that will dissuade Russia and Iran from acting as interdictionist powers, because the US has nothing it can offer that is of equivalent value. To these countries the United States is more valuable as an enemy than as a partner.

If you buy into John Mearsheimer's Offensive Realism, then all Great Powers are power-maximisers and therefore revisionist. Because all Great Powers possess some offensive military capability, Mearsheimer concludes - directly contradicting Defensive Realist Kenneth Waltz - there are no status quo powers. All Great Powers have revisionist aims with the supreme goal of hegemony.

Because Iran does not yet possess nuclear weapons, its revisionist hegemonic strategy is conflict via proxy, which it has executed very successfully. Greater Iran now spans from Lashkar Gar and Gwadar in the East to Tyre in the West, and has Finlandised the Gulf.

Post-Soviet Russia was for years a crippled Great Power (much like Weimar Germany), but its actions in 2014 were a claiming of its stake in Ukraine against the EU Great Power (that is, Bundesrepublik Germany) using the words of NATO-hatred.

As for Appeasement, the British Empire was not ready even for a defensive war with its new radar not working properly till early 1939, and the first squadron of Spitfires becoming operational just a fortnight before Munich. The Royal Navy - the Empire's offensive military capability - was ready, though, and scored victories from the start, so Chamberlain was Britain's Realpolitiker.

"For example, Russia and Iran, avowed opponents of the American system, cannot be said to be revisionist powers for the simple reason that they are too weak to even consider fighting a great power war against the United States and its allies"

States can be locally revisionist even if they are too weak to be globally revisionist. I believe that the focus on global great powers is not useful here. A state's capability and will for power projection also quickly reduces with distance, though the distance penalty to power projection becomes less steep with improving transport and communication. Therefore, a medium power may locally be stronger than a global hegemon.

Being disruptive globally helps countries being revisionist locally.