The Cold-Blooded Case for American Support for Ukraine

The Realist case for arming Ukraine

The Realist school of International Relations has been prominent in its criticism of American support for Ukraine. Realists have long been critical of American foreign policy in general, viewing Washington as having been captured by a dangerously naïve school of liberal theory. Realists view American support for Ukraine as the latest in this irresponsible policy of idealism that fueled NATO expansion into Central and Eastern Europe in defiance of Russian security concerns. To this school, the current crisis is a direct product of prioritizing ideology over America’s strategic interest. From this practical, “Realist” perspective, American interest is better served by avoiding conflict with Russia and the expenditure in resources it requires, even if that means consigning Eastern Europe to the Russian sphere of influence.

Realism argues that however moral the individuals involved in determining foreign policy will be, the anarchic and zero-sum nature of the system and the high stakes involved are deterministic. Regardless of intentions, states are forced by the constraints of the system to prioritize power politics over moral or ideological preferences.

As such, we must put to one side the arguments in favor of supporting Ukraine that find their basis in human rights and international law. In the Realist framework, states are forced to act in accordance with their national interests regardless of whether they violate these principles. Rather, in this article I will argue that from a completely amoral and power-politics oriented standpoint, the United States has a firm national interest in supporting Ukraine and containing Russia.

The Arguments of the Realists

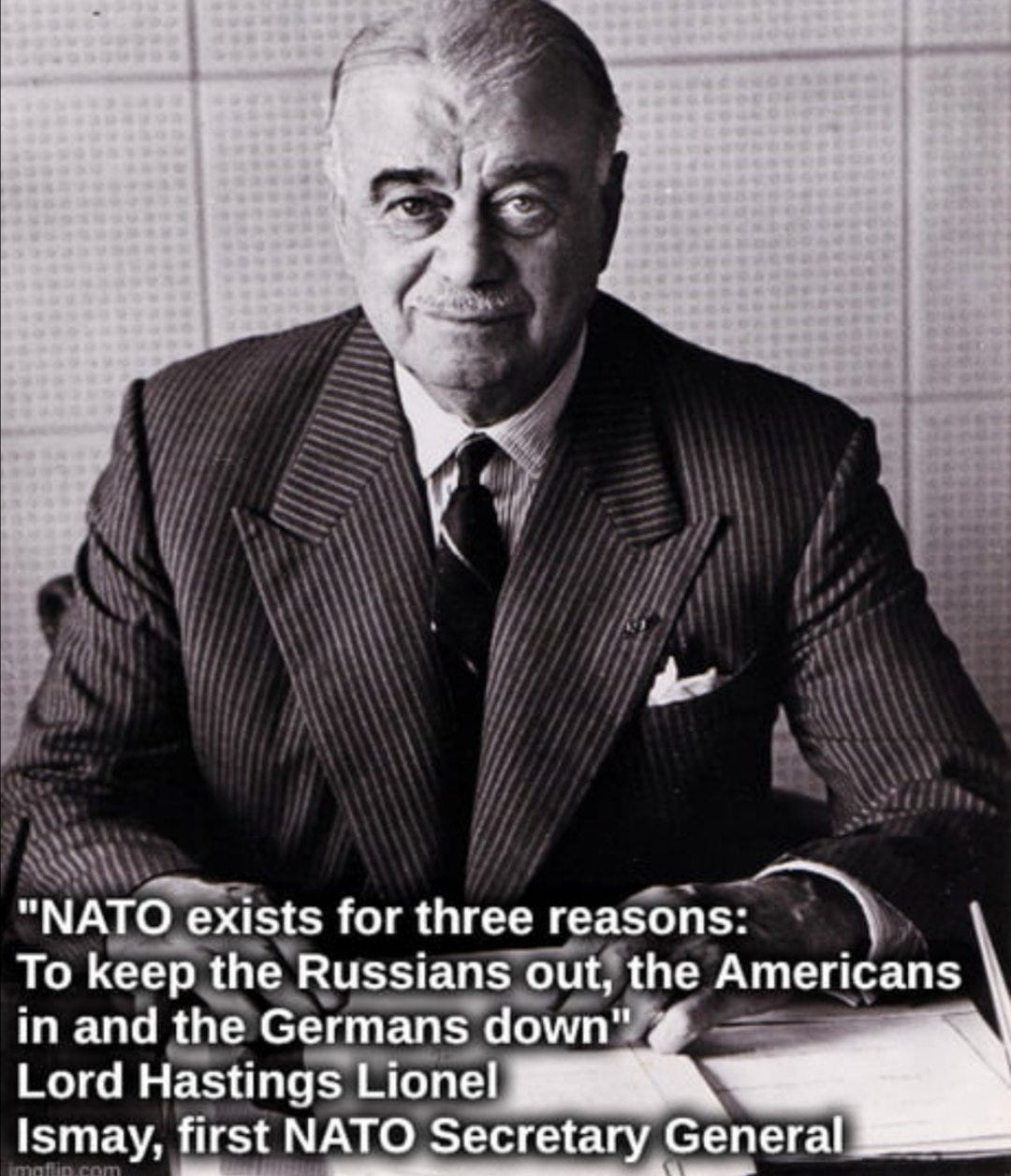

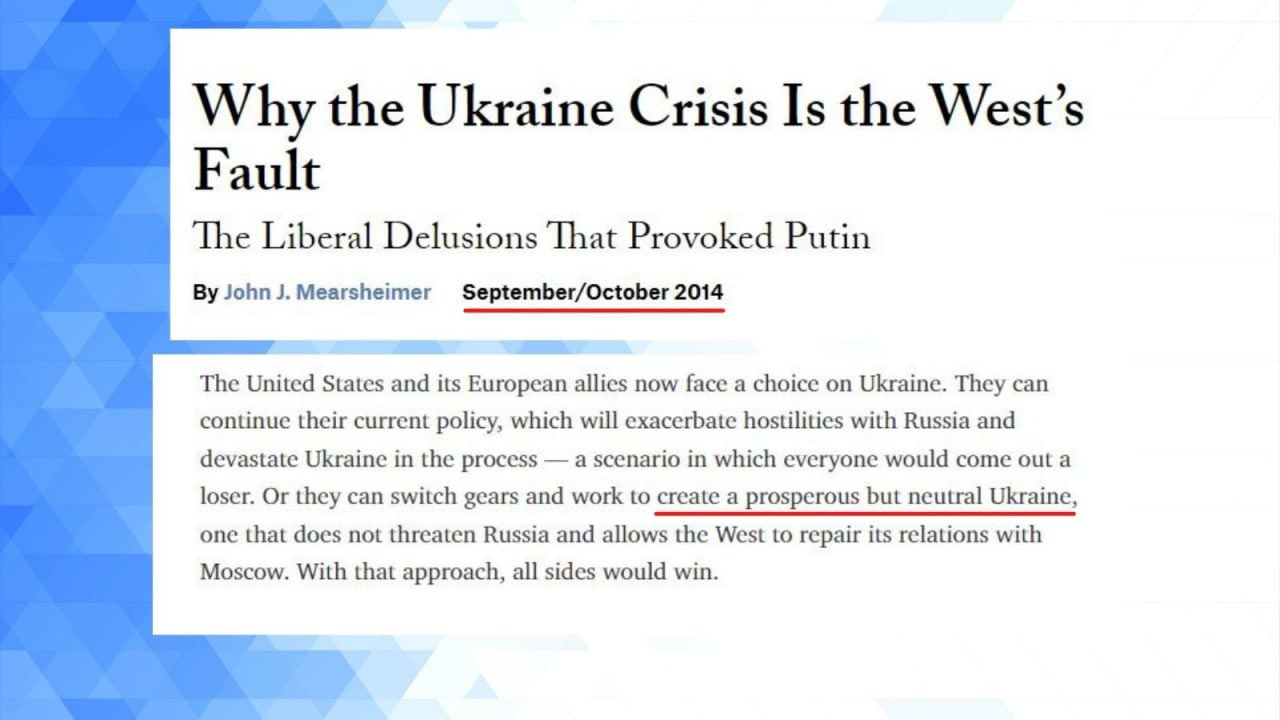

Realists such as Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer have argued that the West is to blame for the war in Ukraine on the grounds that it violated Russia’s sphere of influence, making war inevitable. However, this argument is untenable on Realist grounds, as assigning blame is beyond the scope of Realism. If states are merely rational actors bound by the constraints of an anarchic state system, the system alone can be blamed. From the Realist perspective, the West had no choice but to take the opportunity to intrude on a rival’s sphere of influence, whatever the consequences for Ukraine. National interest is a deterministic force, and forgoing gains, even for the sake of peace, runs counter to Realist expectations for state behavior.

Offensive-Realists like Mearsheimer have also argued that the US is taking advantage of Ukraine by encouraging it to fight an unwinnable war against the Russians. This argument is entirely contradictory to the central thesis of Offensive-Realism, that states are amoral power maximizers by necessity. If that assumption holds true, the accusation of exploitation cannot be used to argue against US aid to Ukraine. Whether or not it benefits Ukraine, forcing Russia to fight a lengthy war for a piece of territory not only makes it costly, but it diminishes the value of the territory acquired. Heavily bombed, mined, and depopulated territory is worth far less than that gained through a fait accompli. To argue that the US is acting against the interests of Ukraine in encouraging and facilitating resistance is itself untenable, but it is also simply a humanitarian argument and beyond the bounds of Realism.

For similar reasons, it is incongruent with Realism to criticize American foreign policy for “fighting to the last Ukrainian.” Regardless of the accuracy of the criticism, if the US were guilty of it, such an approach is the kind of Machiavellianism that forms the heart of Realism. Goading a rival into a difficult war with another country is the highest excellence of power politics. If Realists mean to warn Ukraine that America is only acting in self-interest in its support against Russia, it is an unhelpful point to make. The sovereignty of states depends on their willingness to fight to the last man, and on demonstrating their willingness to do so when it is called into question. For Ukraine, there is no choice but to resist to the bitter end-the war is truly existential. Useful policy advice can only be offered to states that do have a choice in how they engage with the war, and not one facing extinction .

The strongest Realist argument against aid to Ukraine is the danger of escalation. In essence, Realists argue that nothing that can be gained through supporting Ukraine is worth the increased risk of nuclear war it involves. While this is a potent argument against measures such as combat operations against Russian forces to eject them from Ukraine or the imposition of a no-fly zone, it is weak against the supply of arms. There is a firmly established precedent of supplying arms to a state not causing any serious danger of escalation. The Soviets did not invade West Germany because American weapons were being sent to Afghanistan. Nor did the United States invade the Eastern Bloc because Soviet pilots were shooting down American jets over Vietnam. Arms supplies to a third party do not rank as particularly escalatory based on the historical record.

Concerns about escalation are especially weak at the moment on account of the disparity in power between the NATO alliance and the Russians. I have gone over nuclear strategy and theories of escalation in previous articles, but in short, a country can’t threaten to escalate to a level where there is no doubt that it would lose. The entire Russian military is unable to subdue Ukraine. Expanding the war only worsens their strategic situation and is therefore not a decision they would make under any circumstances. As such, no matter how desperate the Russians become on account of Western arms supplies, at no point will beginning a war with NATO appear as an attractive option.

There is always the danger that the Russians decide to begin a nuclear war, but this decision would be a fundamentally irrational one. For the Russian state to take a literally suicidal path is technically possible, but the policy of the United States cannot be directed by that danger. If even the miniscule chance of nuclear war is enough to dissuade the United States from taking action beneficial to its interests, it can expect to have nuclear blackmail repeated. Demonstrating vulnerability to brinkmanship is the surest way to entice such a strategy. If a state is not willing to endure some nuclear risk in defense of its interests, it cannot be a great power in a nuclear world.

To be clear, there are circumstances in which conceding interests to lower the risk of nuclear war is strategically necessary. However, the risk of nuclear escalation in Ukraine remains so low that conceding would increase the danger by incentivizing further confrontation. Just as there is a danger in obstinacy in confrontation, there is a danger in folding at the first opportunity. The status quo of arms supplies to Ukraine is both favorable to American interests and stable. Supplying arms does not increase the likelihood of a clash between NATO and Russian forces and inadvertent escalation.

Realists of the Kissinger school argue that regime type and the disposition of states does matter, drawing the contrast between the integration of post-Napoleonic France into the European order and the diplomatic isolation of Germany following WWI. Kissinger’s essential point is that by making states stakeholders in the international order, they do not become revanchists intent on upending it. If we assume that is true, Kissinger’s paradigm gives us clear instructions when it comes to the current war in Ukraine. Thirty years ago, Russia may have been able to be better integrated into the post-Cold War European order, as France was to the Concert of Europe. However, any opportunity to avoid the development of Russian revanchism has been lost. Revanchist Russia is a fact of life. A revanchist state cannot be made a stakeholder in a system it is defined by opposing. While the comparison is tired, it is nevertheless relevant that neither Hitler’s Germany nor Mussolini’s Italy could be appeased. It’s typical to wield the specter of Munich as a cudgel the moment anyone suggests backing down from a confrontation. However, it must be recognized that when a revanchist state is produced, it must be contained. Avoiding states becoming revanchists is preferable, but once the damage is done, it cannot be reversed by concessions. There is nothing that could be offered to Putin’s Russia that would cause it to suddenly embrace the US-dominated status quo.

Fundamentally, in the Realist framework, the US must continue to support Ukraine because it is the only power capable of acting as a balancer. Abandoning Ukraine would not only allow Russia to gain power relative to the United States, but would damage the ability of the US to act as a balancer in other regions of strategic interest. If the US is not understood as a reliable partner for balancing, states will choose to either attempt to buck-pass or bandwagon for lack of an alternative. The policies of Taiwan and Vietnam are based on an expectation of American support in the event of war with China. If this expectation is undermined, these states will reorient their policies towards either ensuring another state catches the buck, or bandwagoning with China. Both of these strategies would be detrimental to US interests, as they would involve the aggrandizement of China and increase its chances at achieving regional hegemony.

It is not ethical to view Ukraine as a mere means to strengthen America’s position. And it is important to engage with the question as to what the moral stance towards Ukraine is. However, this article aims specifically to address the argument of Realists, that the harsh nature of the international system does not afford the luxury of taking a moral stand. I argue that even under that assumption, supporting Ukraine remains the correct decision.

The Three “B”s

Making this argument requires going over a component of Realist theory, specifically the mechanisms by which states can address their security. There are three approaches that states can take towards their rivals identified by Mearsheimer in The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, these being balancing, buck-passing, and bandwagoning.

Bandwagoning is self-explanatory; a state chooses to make nice with its rival, conceding whatever is in contention for the sake of safety and the hopes of future gains as compensation for its concession and loyalty. This is a strategy most typically employed by minor states outmatched by threatening neighbors. An example would be Hungary in WWII, which joined the Axis both due to its vulnerability to German pressure and hopes of fulfilling its own territorial ambitions. It is distinct from an alliance in that alliance partners are rarely direct security competitors and typically unite based on common adversaries and limited conflicting interests. Bandwagoning is characterized by submission and an unequal relation of power. It is rarely taken by states for which any other option is available.

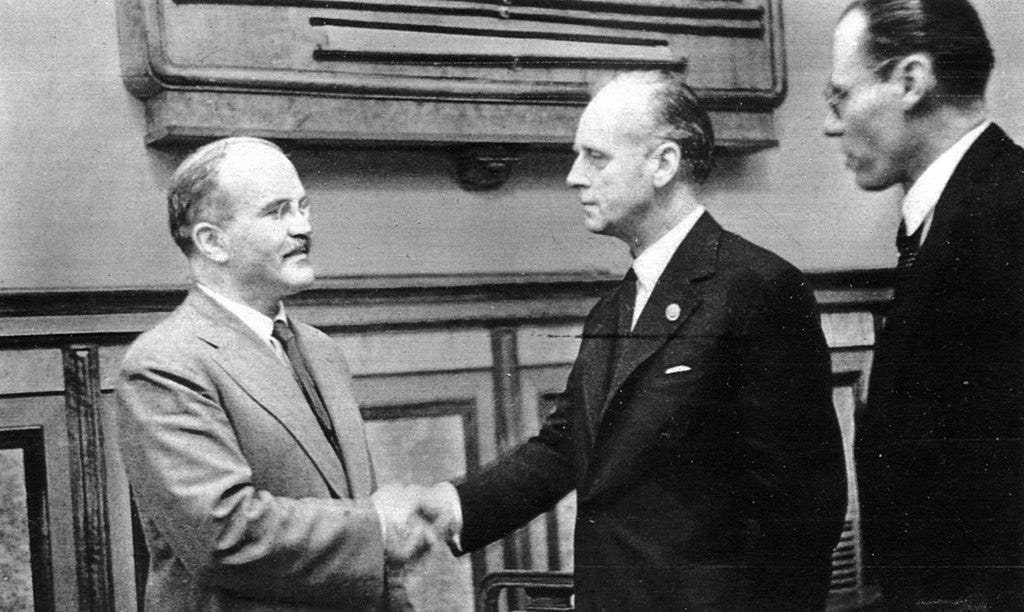

Buck-passing describes attempting to convince a security threat to direct its attention elsewhere, either by appeasement or by presenting too prickly of a target. Both Swiss neutrality and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact were cases of buck-passing. The Swiss refrained from taking any action to contain their aggressive neighbor such as joining the balancing coalition against them because of the costs it would have entailed. Instead, the Swiss ensured that any conquest of their country would be arduous and costly, disproportionate to any gains, causing the Germans to seek more vulnerable targets. As a result, Switzerland passed the costs of containing Nazi Germany to other powers who had to endure lengthy war or occupation.

The Soviet Union made a deal to carve up Eastern Europe with the Nazis and to supply them with the raw materials to feed their war industry, in the hopes that Germany would be too preoccupied fighting the British to open another front. While both buck-passing and bandwagoning may involve concessions to a rival power, bandwagoning involves close cooperation and often outright submission, whereas buck-passing is aimed exclusively at directing their attention elsewhere and forcing some other power to bear the costs of containing it.

Finally, there is balancing. There are two kinds of balancing, external and internal. External balancing can be most simply described as coalition building. When faced with a powerful revisionist state, other states may band together to constitute an opposing force capable of deterring or defeating it. Internal balancing does not directly describe international relations at all, but refers to efforts a state may take to make itself more powerful, for example increasing military spending or embarking on reforms of industrialization. Japanese industrialization is an example of successful internal balancing, whereas the Triple Entente of Russia, France, and the United Kingdom against Germany and Austria-Hungary was a successful example of external balancing.

It may be apparent at this juncture that balancing seems far better than buck-passing or bandwagoning, which raises the question: why are the other approaches necessary? The answer is that balancing is difficult. Internal balancing runs into sharp limits—there was no way for Finland to balance against the Soviet Union in 1939, no matter how much it invested in its armed forces. External balancing is also extraordinarily difficult because of the trust necessary to form a true alliance. Much as in the prisoner’s dilemma (where cooperation leads to the most positive outcome for all participants in the aggregate but betrayal benefits one party at the expense of the other) states are incentivized to buck-pass. Successful buck-passing offers a state the opportunity to weaken two rivals at once, both the aggressor and the buck-catcher.

States will therefore decline opportunities to balance externally either because they hope to pass the buck to the state trying to balance or because they fear having the buck passed to them by a duplicitous alliance partner. Thus, while balancing is extremely powerful for preventing a revisionist state from gaining power, it is very difficult to successfully pull off. When it fails, states resort to less effective strategies, increasing the likelihood of destructive hegemonic war.

Keep Your Enemies Close, Your Hegemon an Ocean Away

It is for this reason that American grand strategy since WWII has been built upon balancing. America’s geographical separation from Europe and Asia has given it the status of an “off-shore balancer.” What this means is that while it can project power into the region, it has no opportunity to dominate the region like a local power might. An off-shore balancer can more easily form partnerships because distance diminishes threats. In the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, France and Britain feared the rising power of Germany far more than they did that of the United States. German troops could march into France, and it could just about be imagined that they cross the channel. Both France and Britain had territorial and hegemonic reasons to anticipate war with Germany. The United States, on the other hand, had no territorial interests in Europe. Even if it had, conducting a war where every man and weapon has to be shipped across an ocean before it can be used is a uniquely unappealing concept. The French and British understood that the Germans would hope to gain a devastating victory at the outset and promptly set about gaining concessions. They also knew that distance made it impossible for the Americans to labor under such illusions.

Thus, the great American moats of the Atlantic and Pacific not only ensure the safety of the continental United States, but also make it a more attractive alliance partner because the “stopping power of water” that Mearsheimer identifies works both ways. Despite America’s formidable navy, conducting and sustaining operations overseas is costly, with many major undertakings being prohibitively so. The United States did conduct war in Europe, but as a balancing power-not as a dominating one for these reasons. As such, when it comes to local threats, states in Europe and Asia not only do not fear American aggression, but cannot hope to pass the buck of containing their neighbors to America. It is scarcely possible to imagine, for example, Russia and the US exclusively fighting one another. Without an adjoining ally, the two powers are too geographically removed to fight, except by ICBM. Both Asian and European states therefore must either be at the mercy of their stronger neighbors or seek a balancing partnership with the United States.

At the same time, the United States is also too powerful to bandwagon with regional powers. There is nothing Russia could offer that would induce the US to back its claims for hegemony over Eastern Europe. Preventing any revisionist power from gaining hegemony is more valuable than anything else that could be offered, so there is no incentive for betrayal.

Instead, the United States represents a prime partner for balancing. States threatened by potential regional hegemons find it beneficial to form balancing coalitions with the United States against their local rivals. The US benefits by preventing other states from coming to dominate their regions and becoming powerful enough to threaten to disrupt the US-backed world order and the partner states benefit through the both conventional and nuclear deterrence that an alliance with the United States offers.

Ukraine is merely the latest case of the US acting as an offshore balancer to contain potential hegemons (or revisionist powers in general). The United States supports Ukraine not because US foreign policy is run by naïve bleeding hearts, but because it represents a chance to weaken Russia and deter other adversaries. By demonstrating that it is willing to provide Ukraine the resources it needs to inflict a punishing defeat on Russia, the US sends a clear signal as to how it may respond to other wars of aggression. In so doing, it raises the costs involved with war, making it a less appealing means of accumulating power. The implicit threat is that aggressor states must reckon not only with the strength of their enemies, but with their potential strength when flooded with American arms.

Abandoning Ukraine would demonstrate the opposite, that the United States is unwilling to contain aggressive states, and therefore be counter to American national interest. Realism tells us that war can be beneficial for the aggressor. It is therefore in the national interest of the United States to foster a more peaceful world through deterrence by robbing rivals of the opportunity to strengthen themselves through war. As a superpower, the United States should favor the diffusion of power in all other cases. That is to say, it should oppose the efforts of strong states to grow stronger. Ukraine is weaker than Russia and Realism assumes power is zero-sum. Thus, a stronger Ukraine and a weaker Russia make the American position increasingly dominant.

Certainly anyone over 50 will want to put the shaft to the ancient enemy. Younger than that need some history lessons.

Several random thoughts this morning as I finish the morning pot of coffee after casting my early ballot yesterday morning. Beginning with the thought that we are seeing an upscale model (thanks to modern technology) of the balance of power/great game played by Britain in the 1800s (with a glance towards Mackinder). NATO and the EU were intended in part to constrain the member states within generally acceptable patterns of policy and behavior- though I sometimes worry that these communities are too tolerant of some of the excesses found in some member states. Sun Tzu and other thinkers in China and India go on at great length and without the added geographical attachments about how smaller to larger states can interact to achieve their goals. As for China, I’m a bit more worried today about managing its decline (as well as Xi’s decline) as its economy shows the strains of past demographic policies, corruption, and the burden of geopolitical and economic decisions made to benefit Xi rather than China. Excellent discussions here, btw.