The Price of Incoherence on the International Stage

What happens when you don't understand alliances?

What makes an alliance? The question of their basis has become starkly relevant on account of America’s newfound ambivalence towards NATO and apparent skepticism towards the idea of non-transactional relationships. Realists or “restrainers” (as some of them seem to have rebranded themselves) maintain that international relations are in fact strictly transactional and so it is wise for the United States to act accordingly. The assumption that power is the sole arbiter of relations between states means embracing coercion and rejecting the concepts of norms and relevance of sentiment. Ordinarily, these theories are confined to classrooms, where they can do little harm. However, one Elbridge Colby (previously best known for claiming anonymous Twitter accounts bullying him were receiving CIA funding) is currently undersecretary of defense for policy and identifies with this school.

The school of Realism holds that power is the basis of all alliances, but this cannot explain the persistent incongruence of alliances with national interest so narrowly defined. In reality, states routinely align themselves in suboptimal ways from the perspective of pure power politics. Considerations of power and security of course play an important role, but these are often defined in subjective terms. Whether a state considers another to be a threat is based not just on considerations of strength, but of intentions.

The relevance of intentions may seem a straightforward contention, but whether the intentions of other states can be known is a matter of serious debate. After all, since there’s no central authority to enforce commitments, whatever papers sovereign entities may sign, they cannot bind their own hands. It follows from the lack of world government that the international system is one of anarchy and so every state must be wary of treachery. This leads to what is known as the “Security Dilemma.” Each state seeks strength to secure its existence which compels other states in turn to increase their own strength. Strength sought for defensive purposes is indistinguishable from that sought for aggression. No matter how peace-loving a state may insist on being, the truth of this will be impossible to rely upon. For states, trust is therefore a luxury that cannot be afforded; the stakes are existential.

From the inscrutability of intentions is derived the idea that all that is relevant is power, capabilities. It is against this that we pose the idea that intentions are in fact legible and essential to understanding the nature of alliances. We argue that the Realist view is a course for disaster because the basis of an alliance is fidelity—it requires that both parties trust in the benevolent intentions of the other to be effective. Each participant forgoes advantages in the moment (or endures hardship and danger) with the understanding that the other side will do the same. This bears the appearance of a transactional relationship—but only the appearance. Unlike a contract between individuals, an alliance has no real binding power in itself. There is no authority above states to bind them to their commitments. Thus, an alliance may exist only as a function of trust. In reality, states do not primarily consider the distribution of power in the international system when choosing alliance partners. Attempts at applying the Realist paradigm will therefore prove counterproductive, as historical cases demonstrate.

The Epoch of Power Politics

To begin, it is necessary to concede that at one time the world described by the Security Dilemma once existed. One of the seminal Realist texts, Niccolo Machiavelli's treatise, The Prince, addressed the world of politics in the Italian city-states, which was characterized by the ruthless pursuit and use of power as the only means of security. Clausewitz noted that while Frederick the Great as a young man wrote “The Anti-Machiavel,” repudiating those principles of statecraft, he made use of them to great effect. Clausewitz cites Voltaire, “[Frederick] spit on it to repel the others.” In both Renaissance Italy and Europe of the 18th century the business of state was a largely personal affair for the proverbial prince. War was much more the sport of kings than the struggle between peoples it would later become. In this situation, alliances were weak, driven by pure power politics. Coalition partners feared one another very nearly as much as their mutual enemy.

But politics did not remain the sport of princes and so the distribution of power was no longer the sole consideration. With the French Revolution and the birth of the nation state, the People took a greater interest and stake in matters of war and peace. No longer were wars fought by small armies largely divorced from popular sentiment. It is this growth in the role of the People that allowed Napoleonic France to dominate so much of Europe. It was reforms in the social as well as military realm that allowed the other European powers to finally overcome France’s armies by fostering the emotional attachment of the people to the state and so to the business of politics.

It is here that a critique of Clausewitz by historian Gerhard Ritter is useful.1 Ritter argues that Clausewitz did not anticipate how the engagement of the people would come to constrain the rational decision-making of the state. With the energies of the people engaged in a war, it was no longer politically possible for the state to conclude peace as it wished. War could generate political forces so powerful that the state—rather than serving as a moderating, rationalizing force—would be consumed by the irrational demand for “total victory.”2 Thus, war was no longer subordinated to politics, but effectively brought politics to serve its own interests.

In his political writings, Clausewitz was concerned with “the People” primarily as a means of increasing the military power of the state. In his view, state policy needed to ensure the energies of the people were invested in the fate of the state (rather than ambivalent as they had been in 1806). While he did not anticipate the development of ideological war directly, Clausewitz’s (secondary) trinity of army, people, and state offers a framework for understanding it. The engagement of the people (corresponding to passion in the primary trinity), strengthens the army, but limits the autonomy of the state (corresponding with the force of reason). It must be remembered that Clausewitz’s famous declaration that “war is merely the continuation of policy with the addition of other means” was only part of his conclusion. War is also “a duel on a larger scale” and has a tendency towards extremity due to this violent nature. Clausewitz expected the rationality of the state to shape the elemental violence that the involvement of the people produced. He did not address the manner in which the popular drive for greater exertions towards victory might deprive the state of its reason, but the aim of On War was to grapple with war as a phenomenon, not to prophesy its development.

The People and Alliances

Ritter wrote in the context of explaining how the carnage of the First World War could be out of all proportion to the political objects nominally in dispute. However, the same principle—that the involvement of the people limits the freedom of action of a state—applies in the case of alliances. States can be constrained by the views of the people. Further, states can influence the views of the people so as to constrain themselves. If a state declares it will or will not do something, failure to fulfill that pledge will have political costs. Like a great ship, public opinion will not turn on a dime. It is notable that the constant shifting of alliances is used as a characteristic of the destruction of truth in George Orwell’s 1984. This—while normal in an era of government that did not involve the people—is presented as the sign of a totally unfree society, for no free people would tolerate the frequent inversion of ally and enemy.

In practice, even unfree societies cannot fully ignore popular sentiment. Nationalism is a force which military realities dictate that states must make use of. The propaganda needed to engage nationalist energies instills expectations for victory. When the struggle is framed in the absolute moral and existential terms that are necessary to call forth self-sacrifice, states cannot abandon or moderate that struggle without the risk of an insurrection on the same terms by which they justified the war. A state may well be powerful enough to endure the displeasure of the people, but war stresses societies in a myriad of ways, such that the breaking point is perilously hard to judge. Thus, even unfree societies must reckon to a lesser or greater extent with the views of the public.

The dangers that would come with “betraying” the cause by making peace gives the continuation of war a logic beyond the policy objectives over which it is fought. A state might have a clear idea under what circumstances it would be prepared to make peace when starting a war. In the actual moment, it is likely to find that making the concessions that would be logical from the view of state interest look like political suicide. We might expect democracies to be especially subject to this kind of pressure as elections directly expose decisionmakers to popular opinion. While we do not deny this greater exposure, democracy also lowers the stakes: a greater chance of losing an election is more easily borne than the consequences of failure in an authoritarian system. As well, for the authoritarians, it is not merely the people they must fear, but other elites who either genuinely believe in the continuation of the struggle or are willing to opportunistically champion popular sentiments.

This is to say that the role of the people in modern politics (and consequently war) has changed such that alliances are no longer able to function under the logic of “pure” power politics. To engage in war will engage the public in the outcome and limit the political possibility of maneuvering, even were it otherwise desirable. Alliances, being attached to the concept of war, engage the people in a similar manner (or must to have any effect) and so bind governments. It is this reciprocal tying of hands in the knot of public(and elite) opinion that brings an alliance into existence in our era, when the participation of the people in the life of the state is no longer avoidable.

Of course, until the hour comes and war is unleashed there is little opportunity to demonstrate true faithfulness. Nevertheless, states seek to both perceive and demonstrate their commitment to their policy. States look for signals of intent to judge the reliability of partners. That alliances function this way is understood or at least intuited by most statesmen and so the signaling of intentions is possible. The idea of “costly signaling” is a concept from game theory, in which states may demonstrate their seriousness by taking actions that ensure they cannot renege without negative consequences.3 The signaling is “costly” because certain courses of action can no longer be chosen without enduring a cost. By voluntarily blocking off certain courses, a state signals that it does not intend to use them—if it did, why would it raise the costs of doing so?

There are a number of ways to accomplish this using popular opinion. To threaten war, it is necessary to drum up the passions of the people for such an enterprise, sentiments that do not vanish with the resolution of a crisis. Likewise, peaceable intentions can be demonstrated by actions that establish expectations of continued peace (though hostile feelings are easier to produce than dissipate). By invoking the public in these ways, states may signal their intentions to one another, thereby breaking the Realist paradigm of unknowable intentions precluding deep alliances.

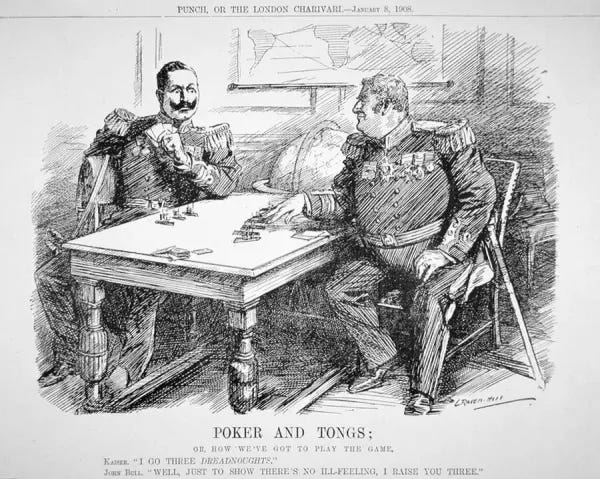

Tirpitz’s Self-defeating Effort

The case of the Anglo-German naval arms race that preceded WWI is trotted out by Realists as evidence that states will conflict, regardless of intentions. As you might have come to expect, a close look at the case of Imperial Germany is a strong argument against the Realist interpretation. In fact, the strategy of the Risikoflotte (“risk fleet,” so named because it would increase the costs for Britain to fight a war with Germany) can be seen as a clear warning against attempting to apply Realist principles and pursuing pure power politics in ignorance of what they signal to other states. Grand Admiral Tirpitz believed that strength was the most critical factor in gaining an alliance with Britain—if the German navy was strong enough, the British could not defend against it without compromising the defense of her empire. The strategy was based on the Machiavellian principle that “it is safer to be feared than loved.” For Tirpitz, how a buildup in naval strength might be perceived was irrelevant; the new disposition of power would force the British to seek accommodation with Germany. Tirpitz convinced many (including the Kaiser) that the fact that Germany could never match the Royal Navy was unimportant—what mattered was shifting the balance, making the prospect of a conflict unaffordable to the British and so making accommodation (if not alliance) attractive.

Tirpitz’s logic was firmly Realist, but not realistic. The massive expansion of the German navy, transparently directed against Britain, could not help but involve popular sentiment in the targeted country. Realists portray this as a tragic inevitability—states cannot understand or trust the intentions of one another and so conflict, even if neither desire to. What this misses is that the Risikoflotte strategy was entirely voluntary; there was no pressing need for Germany to become a naval power. It is in this context that Tirpitz’s strategy appears not merely fantastical, but actively counter-productive: he was creating the circumstances for a war with Britain that would threaten its very existence. The decision to engage in an arms race could only be interpreted by the British as evidence of hostile intent rather than understood as the cack-handed attempt at diplomacy that it was. What British government could consent to an understanding with a Germany that had readied itself for mortal struggle against them?

Not only was Germany’s naval build-up clear evidence of malintent, but it clearly limited the ability of Germany to pursue a credible alliance. A public (and elite circles) prepared for war and sold naval supremacy as the key to national security could not easily be persuaded amity and alliance were the new rule of the day. In threatening war with England, Tirpitz was drifting Germany towards disaster in hopes that the British would blink. Naturally, no country enjoys being threatened, but more than that, the British could not know for certain whether Germany’s course could be altered by a diplomatic agreement—popular sentiment would not turn on a dime. With the Germans unwilling to provide any credible commitments, the British naturally saw no alternative to preparing for a collision. Compounding the absurdity was the fact that the Germans were unwilling to commit to actually abandoning the effort to challenge the British at sea. Part of this may be attributed to the loss of control that comes with the involvement of popular opinion in state affairs, but Tirpitz and the Kaiser were not willing to outright accept British dominance at sea even in exchange for an understanding.

To the British, in the face of incoherent signals, make partnerships with states that were more comprehensible. The United States was able to take advantage of British preoccupation to extract concessions, the same being true of France and Russia. The distinction was the nature of the threats. They were limited, often implicit, and paired with offers of a settlement that did not threaten British vital interests. By contrast, Tirpitz’s plan was a blunderbuss aimed directly at British dominance in the North Sea, the one thing that could actually constitute an existential threat by enabling a foreign army to land on Great Britain. The British could not give in to the Germans so as to focus their attention elsewhere. It was therefore natural to oppose force with force and rely on British superiority to achieve a positive result rather than the purported reasonability of the Germans.

The Deadly Price of Incoherence

What made German foreign policy truly self-defeating was that it was continually strengthening the Entente. The very prospect of war deepened the ties of the Entente both in institutional terms (as staffs, officers, and politicians communicated on the prospect of a coalition war) as well as psychologically. The psychological element should not be understated. If people are accustomed to regarding one state as friend and another foe, that disposition is not easily changed—ordinarily an inversion requires a major change in circumstances, something not possible through mere statecraft. The Germans, lamenting the “ring of steel” of the encircling alliance, could not recognize that the decision of France, England, and Russia to trust and accommodate one another was only possible because of the sword of Damocles they themselves had hung and could not help but to continually jostle.

The configuration of alliances was not merely a reflection of the balance of power, but a product of perceived intent as well. Each time the Germans tried to break the alliance by threat of war they not only proved its necessity, but brought it more firmly into being. The demonstrations of power and complex machinations of the Moroccan crises may not have been doomed to fail, but were certainly inferior to a simple and direct policy of detente and conciliation. The powers of the Entente had many conflicting interests; Tsarist autocracy was considered barbaric by the French and British publics. If Germany had the virtues of quietude and patience, contradictions within the alliance would have flared in time. This, of course, was Bismarck’s policy after 1871: appearing as a “satisfied” power. A country that signals reasonableness and consistency is difficult to maintain an alliance against and is attractive as an alliance partner.

The strategy of Bismarck relied on a certain distance between the people and the alliance structure. After the Revolutions of 1848, European powers were sufficiently wary of public participation in politics that this distance existed. But even before the end of Bismarck’s tenure, the influence of the people began to seriously constrain policy; Bismarck had hoped to avoid embittering France in the Franco-Prussian War, but bowed to military advice and popular opinion in annexing Alsace-Lorraine. This trend continued, such that by the turn of the 20th century, there was no possibility of a policy of a “free hand,” of shifting alliances to maintain balance. Maintaining a balance of power required taking into account the views of the masses, at home and abroad.

Wilhelmine Germany’s failure to comprehend the nature of alliances enforced its own isolation. Britain had considerable conflicting interests with the other Great Powers (certainly more immediate conflicts than with Germany), yet it was willing to come to an understanding with those states. The United Kingdom was able to “pay off” the United States, France, and Russia by settling a variety of territorial disputes on terms that were mutually acceptable. The UK was willing to concede its interests in these cases because it believed they would lead to a lasting understanding with the parties involved. It was not a mere settlement of the particular questions, but one with a view of a general understanding. This spirit of amity was possible because of a sense of consistent policy on both sides—both believed the agreement would be understood in the spirit in which it was meant.

Lack of this consistency is precisely what prevented a lasting understanding with Germany. Did Germany merely wish to join the “imperialist family” by administering more colonies? Or did it wish to end British naval dominance for its own sake? The first was acceptable to the British—German colonies in themselves were no threat. The second possibility was a mortal threat and so had to be decisive in the absence of signaling to the contrary. Germany’s conviction that it could rely on power to secure an alliance caused it to act in a way other states could perceive only as norm-breaking aggression because it neglected to consider what signals its actions sent.

Germany was perceived as threatening to gain hegemony over Europe, not based purely on material factors, but rather because of Germany’s repeated insistence that the balance of power was unacceptable. It was this fear of Germany entering a war against France with unlimited aims that drove British commitment to the Entente. German preponderance on land was at its peak just after unification and it is telling that British entanglement in continental alliances did not come about until well after—only when German actions signaled ambitions towards domination. Faced with a choice between abandoning a naval buildup to signal positive intent to the British and accepting Britain as an enemy, Imperial Germany refused to choose. It built a fleet at great expense that could not challenge the Royal Navy and—rather than pressure the British towards alliance—it did nothing but entrench their commitment to the Entente. A strategy of doing nothing would have been more effective. At the very least it would have been cheaper and given greater odds that an unforeseen incident could weaken the Entente. Peace atrophies an alliance, tension strengthens it.

It is human nature to seek patterns, even when there are none. States are therefore not judged only on their strength, capabilities, or declared disposition, but on the story their actions seem to tell. The straightforward way of addressing this is signaling, both costly and otherwise. States expect one another to act with awareness for how their behavior will be perceived. Dismissing matters of perception as unimportant compared to considerations of power means ignoring the signals that are sent by that behavior. Signaling occurs whether or not you believe in it. States will modify their priorities to protect themselves from erratic or incomprehensible behavior, especially when it’s oriented towards amassing power. The Realist or “restrainer” paradigm of focusing solely on power is thus a course for blundering into a collision.

Gerhard Ritter, The Sword and the Scepter: The Problem of Militarism in Germany, (University of Miami Press, 1969).

This is similar, but distinct, to the argument Isabel Hull makes in Absolute Victory, which focuses on the fixation on total victory within the military culture of the German Army..

See Thomas Schelling, Strategy of Conflict and Arms and Influence.

In the words of Louis Rossman 'If you're going to be the bitch, be the whole bitch!' If you believe might makes right, then you better be ready to fight.

"It wasn't Bosnia, it was the North Sea"? I don't know, I think your argument is insightful but it also feels a bit like an elegant argument is bullying the historical record to align just right..