The Kaiser and His Men: Civil-Military Relations in Wilhelmine Germany

The Limits of the Military Profession - Germany 1871-1914

“We did, indeed, base ourselves upon the philosophy of war of Clausewitz, but we failed to develop it.”1 – KL von Oertzen, German Military Historian

Twilight of the (Demi-)Gods

By the 1870s, Germany was the dominant land power in Europe. It had defeated the preeminent powers on the continent and seemed poised for an era of dominance not seen since Napoleon. However, how quickly Germany’s power was checked and ultimately fell is a cautionary tale about the limits and consequences of the predominance of the military profession. Victories in the war had propelled the Prussian Officer Corps to the status of “demigods” that now held “unquestioned authority and legitimacy” in German politics and society.2 But this status meant they had carte blanche over war planning and became increasingly influential in politics. This produced a civil-military relationship in which, “leaders subordinated political ends to military ends; considerations of war dominated considerations of politics.”3 The German General staff was rapidly departing from Clausewitz's teachings regarding the primacy of policy.

(This post was co-authored by Secretary of Defense Rock, click the button below to check out his excellent posts on civil-military relations!)

By the 1880s, Otto von Bismarck and Helmuth von Moltke, the key architects of German unification both politically and militarily, were nearing the end of their distinguished careers. Now, a younger generation of German nationalists and military officers were chomping at the bit to further expand Germany’s power and formed the engine of what some have called, “a political doomsday machine.”4 The militarists believed preemptive war was the uniform solution to the rising power of Germany’s neighbors. Likewise, success in the wars of unification had led nationalists to dream of a greater Germany “from Berlin to Baghdad.”5 Even in his late career, Bismarck had the experience and gravitas to stymie attempts to initiate a “preventative” war. For instance, in 1887, the senior military leadership cooked up a scheme to convince the Kaiser to declare war on Russia on a whim; they also encouraged Austria-Hungary to do the same. Bismarck stopped it before it became a crisis. But it was a bad omen and showed how the military leadership was increasingly out of control.

Bismarck and Moltke had their issues, but they eventually built a strong relationship, leading the Chief of the General Staff to discuss prospective war plans with the Chancellor, something that had not occurred regularly before and a sign of good civil-military relations. Moltke continued to hold his role until 1888 when he retired. His thinking in his late career had evolved beyond the axiomatic focus on total victory.6 The Battle of Sedan was as complete a victory as one could imagine, yet it did not end the Franco-Prussian War. The ensuing experience of the Volkskrieg (“People’s War”) which encompassed fighting a tough insurgency in France had disillusioned him with the idea of a short war. In one of his final speeches in the Reichstag in 1890, he stated of the next war that,

“If this war breaks out, then its duration and its end will be unforeseeable. The greatest powers of Europe, armed as never before, will be going into battle with each other; not one of them can be crushed so completely in one or two campaigns that it will admit defeat, be compelled to conclude peace under hard terms, and will not come back, even if it is a year later, to renew the struggle. Gentlemen, it may be a war of seven years or thirty years’ duration—and woe to him who sets Europe alight, who rest puts the fuse to the powder keg!”7

Moltke now conceded the need for diplomacy to find a resolution after the army did what it could. “Total victory” was no longer the objective. Unfortunately, by then, the aged Field Marshal was isolated in his work on operational plans and studies. The General Staff had been educated in his original concepts which had been inculcated in the official histories of the wars of unification. Moltke’s genius, shown in the breadth of his thinking, was never absorbed by the institution.

German military historian Gerhard Ritter would distinguish Moltke from his successors for his lack of fatalism. While the Elder Moltke often pressed for preventative war, he made the argument from the military point of view, i.e. that war would be more advantageous now rather than later.8 Moltke was not overly disturbed when Bismarck quashed proposals of preventative war. In contrast to his successors, Moltke was confident in his ability to meet the challenges of war whenever it arrived. He did not view the political situation as intractable. If the statesman did not want to utilize an opportunity for an easy victory in a preventative war, that was the business of the statesman. In other words, Moltke accepted Bismarck’s “right to be wrong.” A working relationship was therefore possible with the statesman who described his policy as “the most dangerous road last.”9

In the final years of their careers, both Bismarck and Moltke foresaw the dangers of a Germany where military prerogatives began to overshadow political ones. Bismarck, the architect of Germany’s rise, understood that the state’s survival hinged not just on military prowess but on the balancing of diplomatic relationships and restrained use of force. Moltke, though a staunch advocate of military autonomy, ultimately recognized the futility of unchecked military power in the context of modern warfare. Their eventual departures left a vacuum, filled by more aggressive military leaders, weak chancellors, and a feckless Kaiser. The political flexibility that had defined Germany’s rise came to be disregarded. As the officer corps grew more entrenched in its dominance, the military’s rigid and totalizing mindset contributed to Germany’s plunge into one of the most destructive conflicts in human history.10

Wilhelm II and Personal Rule

Following the all-too brief reign of Frederick III, his son Wilhelm II, grandson of the first German Emperor, took power in 1888 (known as the “year of the three emperors.” From the start, the young Wilhelm was determined not to be the reserved figure of his grandfather and still less the liberal reformer that his ill-fated father had wished to be. Instead, Wilhelm believed it was his right and duty to be directly involved in the country's governing.

This was completely incompatible with Bismarck’s system, which had centralized power upon his own person. With uncharacteristic focus and subtlety, Wilhelm sought to reclaim the power that his grandfather had ceded to the chancellor. This was not to prove especially difficult; Bismarck’s position had always relied upon his indispensability to the emperor. Thus, when Bismarck offered his resignation (as he often did during disputes) Wilhelm merely accepted it. The last great man of the wars of unification had now disappeared from the balance.

While the German Empire never became a true autocracy, Wilhelm succeeded in creating what historian, and biographer of the Kaiser, John C. Röhl called a “personalist” system.11 The Kaiser had significant power over personnel. Promotions in the officer corps required his assent. Advancement within civil service (from which civilian ministers were appointed) was also dependent on his favor. By exercising this power, Wilhelm was able to ensure the highest levels of the German government were men agreeable to his point of view. Though they were not mere “yes men,” Wilhelm ensured that they were knowingly dependent on his favor for their position. The Kaiser—even to the end of the monarchy—exercised considerable “negative power” (as Röhl termed it.)12 While Wilhelm’s ability to actively make policy was limited, anything he disapproved of was simply not proposed.

Wilhelm II's reign marked a departure from the more restrained leadership of his predecessors, as he sought to assert direct influence over the German Empire's governance and military affairs. This shift toward a more "personalist" system, where loyalty to the Kaiser outweighed true statesmanship, weakened the effectiveness of German leadership and contributed to its eventual strategic missteps. The rigid adherence to the Schlieffen Plan and the technocratic focus on material advantages, such as firepower and mobility, overshadowed the need for adaptable strategic thinking. These failures in both leadership and military planning set the stage for Germany's disastrous involvement in World War I, where an empire led by personalities rather than policies was ill-prepared for the complexities of modern warfare. Ultimately, Wilhelm's influence and the culture of sycophancy he fostered played a pivotal role in leading Germany down the path of ruin.

The Military (Club) Cabinet

Far less mentioned than the General Staff is the military cabinet. While the General Staff was responsible for operations, educating officers, and planning for war, the military cabinet was responsible for personnel decisions, and therefore was decisive in shaping the culture of the officer corps. What’s more, the Flügeladjutanten (aides-de-camp) were almost constantly in the company of the emperor due to Wilhelm’s preference for the company of soldiers.

Good civil-military relations are often a product of productive relationships between civilian leaders and military officials. However, Wilhelm saw himself not as a civilian or as an intermediary, but as a soldier through and through. Thus, the close contact and friendly relations influenced the Kaiser further towards a militaristic view. This is not to say a necessarily aggressive view, but in the sense that Wilhelm held the opinions of soldiers above those of his civilian ministers. These close associates formed something of a clique around the emperor. Wilhelm’s preference for their company and their impact on his views was cause for significant concern. Not only was the military cabinet not accountable to parliament, but it enjoyed far more regular direct access to the monarch than any other institution, including the General Staff, let alone the chancellor or war minister.13

The military cabinet was thus dangerous in that extraordinary influence could wielded upon German policy by officers with no formal responsibility.14 By contrast, the chiefs of the general staff were generally more circumspect, aware that success or failure would rest on their heads. The Kaiser’s military entourage was free to encourage bellicosity and disparage civilian ministers, which they did regularly. Wilhelm’s power over personnel reinforced these tendencies. The military cabinet was staffed with personal associates who agreed with him. These men would then be responsible for managing the promotion of other officers, creating something of a feedback loop. It was no coincidence that before his appointment to Chief of the General Staff the Younger Moltke (nephew of the elder) had become acquainted with the Kaiser as a Flügeladjutant. Likewise, anyone who openly opposed the overbearing influence of the officers was unlikely to be appointed to the civilian cabinet. Wilhelm’s well-known bias incentivized deference amongst civilians to military views and encouraged officers to opine on matters beyond their expertise.

While the General Staff represented the officer corps as a profession, the Military Cabinet reinforced the position of officers as a distinct caste, socially superior to their civilian counterparts. Under Schlieffen’s studious influence, the General Staff maintained its focus on areas of its exclusive responsibility. By contrast, the members of the Military Cabinet had no compunctions about opining on areas beyond their formal responsibility.

The General Staff can therefore be criticized for its isolation, for failing to hold formal consultations on decisions with wide strategic implications. The military cabinet, on the other hand, can be criticized for its continual interference in matters beyond its expertise. This practice typically involved denigrating the views and competence of civilian ministers.

Schlieffen’s Tenure

“Germany cannot hope that a swift and lucky offensive in the west will rid it of one enemy in short order, leaving it free to turn on another. We have only just seen how hard it is to finish a victorious war even against France alone.”

-Helmuth von Moltke the Elder.15

As aforementioned, during Moltke’s late tenure he was occupied with operational studies. This proved deeply consequential as his deputy, protégé, and eventual successor Count Alfred von Waldersee was a shamelessly political general. Waldersee maneuvered to increase the power of the General Staff and reduce its accountability to the war ministry (and ultimately parliament). Waldersee was a strong influence on the young Wilhelm, reinforcing his desires to be harsh towards parliament, even encouraging a military coup if the civilians rejected this firm line.16 However, Waldersee only lasted from 1888-1891 in the office of Chief of the General Staff. His defeat of the emperor in the annual Kaisermanöver (“imperial exercises”) and subsequent critique made his tenure short. The Chief of the General Staff was clearly no less reliant on the Kaiser’s goodwill than his civilian counterparts.

Waldersee’s downfall brought something of an inversion, as his successor was very much apolitical. The famous Count Alfred von Schlieffen was a firm guardian of the traditions and prestige of the General Staff. Unlike Waldersee, he did not seek political influence or office and was firmly convinced of the need to uphold the privileges of the crown. Unlike Waldersee, (and perhaps influenced by his fate) Schlieffen made sure Wilhelm was victorious in the annual maneuvers, typically by cavalry charge.17 This virtually eliminated any military utility they might have, but Schlieffen considered it necessary to maintain the dignity of the crown. Schlieffen proved even less politically inclined than the Elder Moltke, with no evidence that he so much as suggested preventative war.18

In contrast to his successors, the Elder Moltke was far more broadly educated. The younger Moltke had a liberal education and was fundamentally humanist in outlook. Moltke ascribed his military career to mere chance, suggesting he might have been a writer otherwise. Succeeding general staff officers were educated in a far more specialized way. None exhibited this more clearly than Count Alfred von Schlieffen. The new Chief of the General Staff took an academic, almost monastic approach to his work and demanded the same from his subordinates. The General Staff was to be independent of outside influence, but also removed from influencing state policy. The increased influence of the military therefore did not come from the intentions of this Chief of the General Staff.

But with the fin de siècle and “scientific” theories like social Darwinism, the future seemed much surer than it had ever been. Advances in the physical sciences also gave a greater sense of certainty to the understanding of the world and thus fed the sense of inevitability. This emphasis on the scientific and technical served to elevate military expertise and the judgment of those who held it.

This was further reinforced by the narrower, increasingly technical education of the officer corps which contributed to a focus on the purely military situation and fed the sense of fatalism. The Elder Moltke had appreciated, if not entirely agreed with, Bismarck’s analogy of statesmanship as wandering towards a set goal through a foggy and uncharted forest. Even the keenest minds and best-founded analysis could not divine the future with sufficient certainty to make great policy decisions on such a basis. Least of all was Bismarck willing to venture into a preventative war, famously decrying it as “suicide for fear of death.”

Schlieffen, though anything but a political general, therefore nevertheless exerted considerable indirect influence on German policy. The authority to devise operational plans was exclusive to the General Staff as it was considered a purely technical matter. Yet this was clear fiction. Even by 1890s there was discussion of the violation of Belgian neutrality in a war with France as a matter of “military necessity” with little thinking of the political consequences.

This comes to the core of the problem: (what Ritter calls the conflict between Sword and Scepter “Kriegshandwerk und Staatskunst”) the German empire had no formal authority through which to arbitrate between political and military advantages. Even the informing of political authority of politically significant decisions like the violation of neutral countries was left to informal channels. The decisive factor in civil-military relations was the Kaiser. Under the reign of Wilhelm I, Bismarck’s skill and favor had been able to produce a (mostly) functional model of civil-military relations. However, Wilhelm II considered himself a pure partisan for “his” (as supreme warlord) soldiers. His jealous defense of their rights and authority prevented civilians from imposing policy priorities on operational plans.

Schlieffen’s emphasis on a clear separation from political questions de facto reinforced the supremacy of military judgment. Given the disposition of the Kaiser, only active efforts on the part of military leadership would have been able to permit policy to influence operations. One historian called Schlieffen “the greatest exponent of 'pure military thinking.” But this wasn’t limited solely to Schlieffen as the German Army increasingly “concentrated on three focal points: intelligence, mobility, and firepower. All were material based. All appeared susceptible to bureaucratic and technocratic virtues of management and control.” This focus on material advantages and technocratic management, however, obscured the deeper strategic flaws in the German military’s approach, contributing to the failure to adapt to the evolving nature of modern warfare.

Schlieffen eventually came up with a plan that would become infamously known as the Schlieffen Plan. It aimed to avoid a prolonged two-front war by defeating France before turning to fight Russia. The plan involved a rapid invasion of France through neutral Belgium and the Netherlands, bypassing French defenses, and destroying the French Army in a grand encirclement.19 Afterward, German forces would shift east to confront Russia, which was expected to mobilize more slowly. Henry Kissinger would remark that his plan was, “as brilliant as it was reckless.”20 The plan hinged on a fundamental belief that the German army would be outnumbered no matter what and would have to use speed and maneuver to win victory. There is still a robust historical debate to the extent that Schlieffen and other German officers trusted the veracity of their plan or if they could even win a great European war. The destruction and taking of documents during World War II has left historians still trying to piece together this perspective.21

[It is] senseless to consult professional soldiers in drawing up plans for war, asking them to give ‘purely military’ opinions on what cabinets should do. Even more senseless is the demand by the theoreticians that all available resources for war should be turned over to the generals, for them to use in drawing up military plans for a war or a campaign.

-Carl von Clausewitz

There is substantial evidence that serious doubts existed about the Schlieffen Plan, as the German General Staff's own studies suggested that success was improbable even under ideal conditions, instead depending on “many lucky accidents,” as one historian concluded.22 Schlieffen himself even acknowledged at one point that his plan was “an enterprise for which we are too weak.”23 Schlieffen’s eventual successor, the Younger Moltke, supposedly told Wilhelm that even a war solely against France would be grim: “[It] cannot be won in one decisive battle but will turn into a long and tedious struggle with a country that will not give up before the strength of its entire people has been broken. Our own people too will be utterly exhausted, even if we should be victorious.”24 But if all these doubts were present and in writing in the way some historians present them, why did the German military go ahead with the plan anyways? The two possible explanations are that there were enough officers that both believed in the plan and felt compelled to carry out the duty regardless of the personal beliefs and that civilians quite frankly weren’t able to keep the army from its worst impulses. By the July Crisis, the Germany military was a fully loaded train that couldn’t be stopped even if the conductors (the German officer corps) wanted to.

The Cult of the Offensive and Wargaming

German unification had been marked by Bismarck’s careful maneuvering of European power politics ensuring that coalitions would not intervene or serve a check. After Bismarck’s departure, the Franco-Russian Alliance officially signed on 1894 upset that careful balance and created the nightmare strategic scenario for Germany; a war on two fronts. Bismarck had anticipated the repercussions of Germany’s great military victories and, in 1876, made an unsuccessful attempt to prevent a European coalition. He sought a guarantee from Russia to maintain Alsace-Lorraine as part of Germany in exchange for Germany’s unconditional support of Russian policy in the East. But by 1894, Bismarck was out of the picture and lesser men had taken his place who could not prevent the European powers inevitably marshaling against them.

The German General Staff quickly threw itself into wargames (“kriegsspiel”) attempting to construct a plan that could solve this conundrum. The first wargame had been created in Prussia in 1780 by Johann Christian Ludwig Hellwig and had become an integral part of the German military profession and become a cult like activity.25 A wargame is a simulation that models military operations, strategic planning, or conflict scenarios to explore decision-making processes, test tactics, and evaluate potential outcomes26. Participants engage in a structured environment where they assume roles, make strategic choices, and analyze the consequences of their actions, often using rules, maps, and models to replicate real-world situations. In particular, the general staff centered its wargaming around offensive operations and attacking directly at the enemy to achieve “total victory.” This became particularly pronounced during Schlieffen’s tenure and led to a phenomenon that became known as the “Cult of the Offensive.”

The “Cult of the Offensive” is a term that rose to prominence in the 1980’s and refers to a military doctrine and mindset prevalent among European military leaders before and during World War I, which emphasized the strategic advantage of offensive operations over defensive ones.27 This belief was rooted in a misreading of Clausewitz that led to the assumption that rapid and aggressive attacks would lead to quick and decisive victories, thereby preventing prolonged and costly wars. The doctrine influenced military planning and led to the development of strategies that prioritized offensive maneuvers, often at the expense of any defensive considerations. It was a strange development that as the offensive became more entrenched, technological developments increasingly made the defense the favorite.

Proponents of the cult of the offensive, such as Jack Snyder, argue that this occurred in part due to, “the complete absence of civilian control over plans and doctrine, which provided no check on the natural tendency of mature military organizations to institutionalize and dogmatize doctrines that support the organizational goals of prestige, autonomy, and the elimination of novelty and uncertainty.”28 As a result, this offensive doctrine not only shaped the disastrous military strategies of World War I but also highlighted the dangers of unchecked military autonomy and the lack of critical civilian oversight in shaping national defense policies.

The study of history may be 20/20, but the general staff strategists uncannily predicted the outcomes of their plans long before they unfolded. While conducting a wargame where he was in charge of the French army, Schlieffen managed to defeat his own plan with a railway maneuver that the French general Joseph Joffre would use at the battle of the Marne in the fall of 1914. In another war game centered in the East, Schlieffen used railway mobility to defeat a Russian advance around the Masurian Lakes, which mirrored the maneuver that led to the encirclement of the Russian 2nd Army at Tannenberg in August 1914. However, the preconceived notions and biases that the participants brought to the simulated environment ensured the general staff would not yield key lessons even though they had practically played out what would happen before it did. This isn’t to say that some were alarmed. General Friedrich Köpke, the quartermaster of the general staff soberly concluded that,

Even with the most offensive spirit... nothing more can be achieved than a tedious and bloody crawling forward step by step here and there by way of an ordinary attack in siege style in order to slowly win some advantages…There are sufficient indications that future warfare will look different from the campaign in 1870–1. We cannot expect rapid and decisive victories.29

In addition to the constant wargames centered on offensive operations, several games were run based on a defensive strategy in the west as an academic exercise. Much to the frustration of offensively inclined officers, the wargames revealed that the French Army would struggle to achieve a decisive breakthrough through Alsace-Lorraine against even a modest defensive force. The outcome suggested that its strategic planning was flawed and needed change. However, in subsequent years, when war games with this scenario were repeated, the German defenders were given fewer troops, Belgian and Dutch forces were arbitrarily added to the attacking side without any reasons besides convenience, and given an advantage in mobility that would have been impossible given the lack of infrastructure and difficulty of the wooded terrain. German critics noticed and accused Schlieffen of applying a double standard, arbitrarily giving the attacker undue advantages when it should have been the opposite.30 This manipulation of war game scenarios not only reflected the German military’s reluctance to confront the flaws in their offensive doctrine but also foreshadowed the strategic miscalculations that would contribute to the deadlock and devastation of World War I.

At the very least, wargaming showed that the German military was facing a serious strategic problem that would not be solved by brute military force. There isn’t historical evidence to suggest that there was serious consideration to fundamentally change German war planning. This stems from the fact that the militaries of that era were “seeing war more likely than it really is; they increase its likelihood by adopting offensive plans and buying offensive forces. In this way, the perception that war is inevitable becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”31 A strategic change would have entailed potentially reaching a decision in the East before the west or splitting their forces equally to go on the strategic defense, especially as technology began to favor the defender. However, in a 1912 wargame based on this scenario, it was determined that by around the 45-day mark, the French would capture the fortress city of Metz and be positioned to break through into the German heartland, while no decisive outcome had been achieved on the Eastern Front. It is difficult to determine the extent to which the wargame was influenced by the offensive biases prevalent in many simulations of the time. However, proponents of the Schlieffen Plan could point to the outcome as evidence that a defensive posture offered a slimmer chance of victory than launching an attack.

In many ways, this reasoning was sound—both Charles XII and Napoleon had seen their armies destroyed deep within Russia centuries earlier. However, the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 suggested that the Russian Bear might not be as formidable as it once appeared. Victory might not have entailed capturing Moscow or St. Petersburg but rather inflicting enough military defeats to force the Russian government to sue for peace or collapse (which coincidentally is what happened) but the German General Staff had embraced the concept of “total victory” even though its chief architect, Moltke the Elder, had dissociated himself from it many years prior. Yet history often proves stranger than fiction, as the events of 1915—when Germany and Austria-Hungary went on the offensive against Russia while staying on the defensive in the West—closely mirrored the elder Moltke’s expectations from the 1890s, when he had resigned himself to a similar outcome in a war against Russia and France.

If civilians were present to observe these war games or received reports, they certainly would have been alarmed but the general staff had insulated itself from criticism or civilian oversight. The general staff had repeatedly assured the civilian leadership that it could win a war quickly, and why would they doubt them? To that point, Germany had crushed Austria, France, and the other countries around it. This self-confidence was punctuated by General Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, Chief of the General Staff during the height of the July Crisis, who angrily told a fellow officer that the objections of mere civilians should be ignored.32 Despite ample evidence from war games and historical precedent that defensive strategies could have yielded more favorable (albeit less total) outcomes, the German General Staff remained fixated on offensive operations, driven by a combination of institutional inertia, prestige, and the belief in rapid victory. Civilian oversight, which could have tempered these strategic miscalculations, was either absent or dismissed outright, contributing to the catastrophic outcomes of World War I. As the war unfolded, the very scenarios that had been predicted—stalemates, attrition, and drawn-out conflicts—became a reality. Had the German leadership heeded the warnings from their own war games and considered alternatives, the course of history might have been very different.

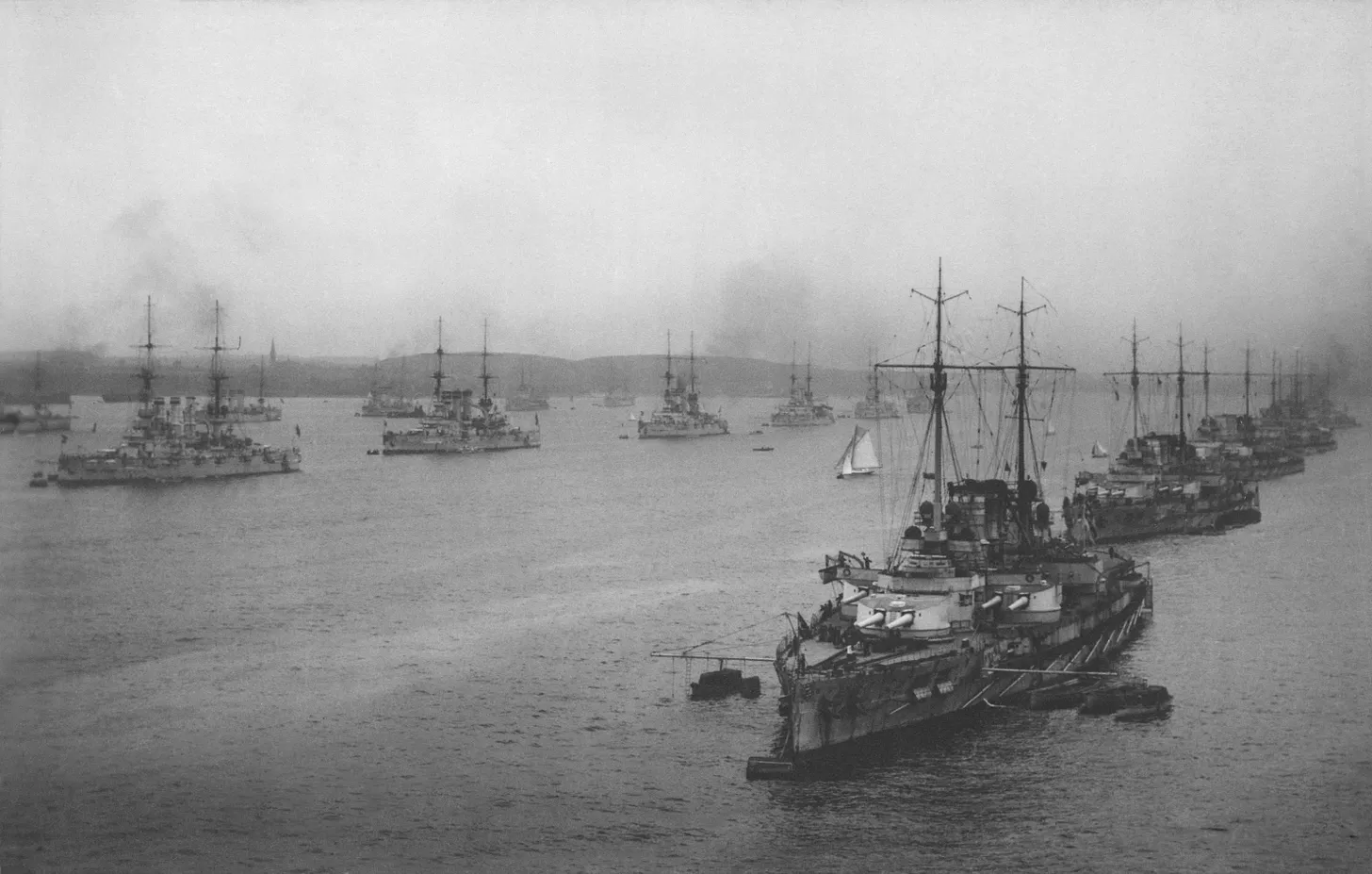

The Vibes Based Naval Arms Race

The Wilhelmine era inaugurated a new importance for the German navy. Prussia’s navy had been a virtual non-entity during the wars of unification. There was a broad consensus that this was unacceptable given Germany’s new position as a great power. Wilhelm in particular, in part due to personal reasons, desired a grand fleet by which Germany could claim its “place in the sun.” To support this, the navalists had no compunction with dabbling in politics, and so created a “naval league,” an organization which quickly swelled in membership. This new policy added a frustrating dimension to German civil-military relations, with a new “naval cabinet” joining the Kaiser’s entourage, further limiting the access of civilians to the “all-highest.”

The appetite to be a great power undermined a historic German-British relationship. Even as tensions grew, there were still negotiations to reach some sort of détente or even an alliance. The British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Joshua Chamberlain, had at one point even called for a “Teutonic” alliance between Great Britain, Germany, and the United States.33 The German Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow had attempted to get Britain to join the Triple Alliance in exchange for curtailing the naval build up which was rejected out of hand. As Henry Kissinger observed this was because, they “simply did not have enough parallel interest to justify the formal global alliance imperial Germany craved.”34 So, Germany decided to pursue a dual policy towards Great Britain of détente while understanding that they were the primary competitor in Germany’s chase of continental dominance. At the same time, they also competed in an arms race attempting to build a blue water navy at a breakneck pace to challenge the Royal Navy’s control of the North Sea.

Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz was the architect behind Germany’s naval strategy. A forceful personality with whom even the Kaiser hated to conflict, Tirpitz was not opposed to alignment with Britain. What undermined this process was Tirpitz’s steadfast belief that the only thing that could compel Britain to ally with Germany was sufficient naval strength to challenge it. His basic concept was that a large enough fleet would mean that war with Germany would force Britain to concentrate so much of its fleet that it would be unable to defend its colonies. He called this the Risikoflotte (“risk fleet”) referring to the idea that it would make conflict with Germany too risky for Britain to accept. This goal meant that under no circumstances could the German rate of shipbuilding be reduced. However, this led Germany into a situation where the one concession Britain desired—a reduction in the rate of shipbuilding—was the one that they could not make. Tirpitz’s conviction, ultimately a diplomatic assessment, was simply completely wrong. As Gerhard Ritter writes,

But the notion held by German navy fanatics that England, the notorious “nation of shopkeepers,” would be deterred from maintaining its supremacy at sea and the security of its islands by financial and technical impediments represented a complete misreading of the character of this proud nation. German diplomats never ceased to warn against this delusion; and when Tirpitz, citing the reports of his naval attaches, belittled British arms zeal as nothing but propaganda... he was merely displaying his limited political outlook.35

Tirpitz was able to sway the Kaiser to his view.36 What this meant was that meaningful political agreement with Britain was precluded. The British wanted the Germans to reduce the rate of construction so as to ease the financial burden of the arms race. Yet this was precisely the thing that Tirpitz and the Kaiser would not compromise on.

What’s more is that Great Britain welcomed a détente despite the frustration over previous attempts to reach an alliance. Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey stated to his colleagues that, “so long as Bethmann Hollweg is Chancellor we will cooperate with Germany for the peace of Europe.”37 Bethmann had made a détente a center piece of his foreign policy and yet at the same time, the German Navy was aiming to build a battle fleet of at least sixty modern capital ships including battleships, armored cruisers, and battle cruisers along with overseas bases and infrastructure.38 It was another sign that at the end of the day, the military had more control over the direction of German foreign policy than the civilians.

Like the chancellor, the German ambassador to London, an extremely talented diplomat, saw a clear opportunity for agreement with the British. However, Admiral Tirpitz, author of Germany’s naval build-up, was determined that only great strength could convince the British of the necessity of alliance. The diplomats accurately reported that the British would perceive such a massive arms program as a challenge and insult. The naval attaché to London would provide his own reports, denigrating the ambassador and accusing the British of bad faith. These, addressed to Tirpitz, inevitably found their way to the Kaiser (it was “his” navy, after all) who left marginal notes approving of this bellicosity.39 The Kaiser was also utterly intransigent when it came to reducing the rate of construction as “legally authorized” under the naval bills, despite the fact that abandoning the effort to challenge the British at sea was a prerequisite to any agreement.40

Bethmann dared not propose the material concessions the British would have required for a naval pact and so negotiations simply faded away. Bethmann blamed this on German public opinion, however as, Ritter reflected,

Whether he was right in this contention remains doubtful... but such an agreement almost certainly would have brought a veto from the Kaiser and his naval advisers. Indeed, Bethmann could not even have put forward such an agreement without risking instant dismissal. There was a limit beyond which civilian authority could not go in Wilhelminian Germany—and that limit would have here been transgressed.41

This kind of ambivalence and strategic incoherence was the routine product of a system that lacked formal mechanisms for coordinating grand strategy.

German land power had cornered France to make an alliance with Russia. The Naval arms race would do the same to Britain. The Franco-Japanese Treaty of 1907 at least made a British alliance with France that much more formal even though it was technically informal. German military and civilian officials were under no illusion of this. In December of 1912, Great Britain had said as much when they told Germany that they would intervene on behalf of France even if they weren’t a treaty ally. The potential for a British naval blockade made a quick decisive outcome that much more apparent even though most German military officials knew that it was extremely unlikely.

The Younger Moltke and “Preventative War”

Helmuth von Moltke the Younger is a difficult character to uncover, but one essential to understanding the panoply of forces that produced WWI.42 Moltke died in 1916, providing him little opportunity to defend his tenure. His widow had intended to publish an exculpatory collection of evidence of the chaos of German war planning before 1914. However, by then it was 1919, and the documents were deemed harmful to Germany’s attempt to avoid the blame for the war and so not published. This would prove fateful; the documents would be destroyed in World War II.

Moltke therefore proved an ideal scapegoat for the “Schlieffen School.” For the Schlieffen School (mostly officers trained by Schlieffen), the Schlieffen Plan was a true recipe for victory bungled by incompetent execution. However, recent scholarship has shown a more nuanced picture. While Schlieffen did not fully approve of his successor, Moltke was a faithful student of Schlieffen’s concepts. The modifications he made to the plan were not because of a difference in opinion, but of circumstance. Following Schlieffen’s retirement, the French army became more aggressive, necessitating a stronger defense of the Rhine. Likewise, Russian strength and mobilization speed increased, necessitating a greater force allocated to the East. Moltke was also more realistic about the logistical limitations of the all-important right wing of the German offensive. While Schlieffen (allegedly with his dying breath) insisted “keep the right wing strong,” there were simply only so many divisions that could practically advance there. Moltke did his best to adapt the Schlieffen Plan to these changing circumstances, though with mounting fear that the strength of the Entente had placed victory beyond Germany’s strength.

Despite awareness of the long odds, officers continued to press for preventative war in succeeding European crises.43 The term “preventative war” did not mean “preempting the attack of hostile powers” but rather to initiate a war while the strategic balance was most favorable for Germany. While, as mentioned, they had their doubts about the surety of victory, they believed the odds would only get worse. The Schlieffen Plan had been designed for a one-front war against France (in 1905, the year of Schlieffen’s retirement, Russia was in the throes of revolution). Though adapted in later years, the plan remained tenable only so long as Germany had the chance to defeat France before Russian mobilization was completed. As the Russian army expanded and its rail system modernized, the General Staff saw the Schlieffen Plan nearing its expiration date.

The General Staff saw no alternative to Schlieffen’s concept because of its axiomatic focus on total victory. The kind of limited victory that the Elder Moltke had settled for in his later war plans had never entered the vocabulary of the General Staff. As such, the General Staff pressed strongly for war (which it believed was inevitable) to break out before the balance of power swung further against Germany.

The only alternative to this would have been to frankly state the perilous situation in which Germany stood militarily and admit that total military victory was out of reach and German diplomacy would need to be reoriented around this fact. Not only would this course of action been antithetical to the proud traditions of the officer corps, but it would also have been viewed as unacceptably political. What’s more, the Kaiser would have likely viewed such behavior as cowardly if not outright insubordinate. Once again, the Kaiser’s power over personnel decisions meant uncomfortable topics were not broached for fear of instant dismissal.

It is not entirely unjust to accuse German leaders of cowardice or careerism in avoiding these conversations. However, they—like so many who serve under capricious or incompetent heads of state—justified their silence and continued service under the logic of harm reduction. If they resigned (or clashed with the Kaiser leading to their dismissal) they knew they would be replaced by someone more compliant. The Kaiser’s power over personnel meant they understood clearly that they had no leverage.

The Chiefs of the General Staff, for all their influence, were incentivized to focus on the areas of their exclusive responsibility. Nevertheless, the younger Moltke was not passive in his efforts for war. He resumed contact with the Austro-Hungarian General Staff, assuring it of German support should Austria choose war in a crisis. As aforementioned, when crises came to Europe (some instigated by the German foreign ministry) he pressed the chancellor and Kaiser for a preventative war. Both, to their credit, while willing to risk war, would not choose it.

Perhaps most decisively, Moltke and his deputy, Erich von Ludendorff,44 made the decision to hinge the operational plan on an attack on the Belgian city of Liège (hosting a critical rail juncture) before the neutral country could mobilize.45 This modification was made because Moltke desired to avoid violating Dutch neutrality (as Schlieffen had called for). He wisely understood Germany could afford no more enemies and that invading the Netherlands would mean increasing the distance the German right wing would have to cover to gain the French flank, decreasing the odds of success. What’s more, Moltke hoped that Dutch neutrality would allow it to act as a “windpipe” in the event of a long war and a British blockade. However, avoiding Dutch territory complicated German logistics, necessitating the swift seizure of Liège to allow the offensive to meet its strict timetables.

This was a strictly operational decision, made on technical grounds. As such, neither the chancellor nor the Kaiser were informed of this detail of the plan (operational plans were kept strictly secret, with the prior year’s being systematically burned). However, as perceptive readers may have noticed, the need for a coup de main against a neutral country before it mobilized severely limited German strategic flexibility. There was only one deployment plan for war in the West (and only one at all after 1913). In a crisis, Germany was therefore bound to attack before the Belgians manned Liège’s fortifications. Yet this all-important point-of-no-return was unknown to the Kaiser, chancellor, and foreign minister. The General Staff had effectively stripped the Kaiser and civilian leaders of their “right to be wrong.”

Thus, the General Staff had drastically increased the likelihood of war in that the point-of-no-return was kept obscured from those who would be responsible for bring Germany to the brink. As would occur in 1914 during the July Crisis, the Kaiser and his minister could not understand why Moltke was pressing so strongly for war. As historian Annika Mombauer puts it, “Only Moltke knew that every hour counted.”46 The General Staff had—intentionally or not—engineered a situation in which political leadership would have to choose war or abandon its only operational plan. While political leadership was reticent to take this step (especially without the details of the plan) contributing to Moltke’s nervous breakdown, the General Staff ultimately got the war it so desired at the next crisis Germany found itself in. If the coup de main on Liège had been devised as a ploy to force political leadership to engage in a preventative war, it had succeeded.

Ultimately, the predominance of the military over German policy—both foreign and domestic—created an environment in which civilian leaders like Bethmann Hollweg were sidelined, and aggressive military strategies took precedence. This imbalance of prestige, coupled with the narrow, fatalistic worldview of military leaders, contributed to Germany's march toward war, with little room to acknowledge alternative diplomatic or strategic approaches.

Hurtling towards Armageddon

Germany's internal governance and foreign policy during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II were shaped by a deeply flawed civil-military relationship, marked by an increasing dominance of military perspectives and the suppression of civilian oversight. From the outset of his rule, Wilhelm II sought a hands-on approach to governance, asserting his influence in key appointments, from civil servants to military officers. This created a “personalist” system, as historian John C. Röhl has noted, where the Kaiser exerted significant “negative power,” ensuring that policies or plans he disagreed with were simply never proposed.

Wilhelm's preference for surrounding himself with individuals who flattered and deferred to him, especially in the military, fostered a decision-making environment detached from practical civilian concerns. The elevation of officers like the younger Helmuth von Moltke, who gained favor as a Flügeladjutant (aide-de-camp) to the Kaiser, exemplified this favoritism. This concentration of power in Wilhelm's hands allowed him to marginalize civilian ministers, further entrenching a militaristic worldview within the government. While the German Empire never became a full autocracy, Wilhelm's central role in key appointments ensured that the lines between military and civilian authority were blurred, with military leaders often steering policy, especially in matters of foreign and defense strategies.

One of the key military figures who exemplified the shift towards a more militarized approach was Count Alfred von Schlieffen, Chief of the General Staff (1891-1906). Schlieffen's narrow, specialized military education reflected the broader trend of officers becoming less attuned to the broader political, diplomatic, and cultural considerations that had previously informed leaders like the elder Moltke. As historian Herbert Rosinski summarized, “thus in Schlieffen’s hands the all-embracing heritage of the German school of strategy contracted into one central idea of the coordination of the whole act of war, its direction upon the overthrow of the enemy’s power of resistance, its concentration upon that one point even to the total disregard of all distracting side issues.”47 This narrow focus fed a dangerous sense of fatalism, underpinned by social Darwinism and a belief in the inevitability of conflict. Schlieffen, deeply influenced by these ideas, is remembered as the architect of the famous Schlieffen Plan, a war strategy designed to solve the problem of “two front war” through a knock-out blow against France.

With a fatalistic worldview, the General Staff, led by the Younger Moltke, clung to Schlieffen's plan, despite its limitations, manipulating war games and operational planning to justify their aggressive strategies. Civilian leaders, marginalized by a system that concentrated power in the hands of the Kaiser and military officials, were left with little knowledge or control over the crucial decisions that would lead to war. The plan’s rigid timetable and the secrecy surrounding the operational details—such as the pivotal attack on Liège—bound political leadership to a path of war. As diplomatic alternatives were sidelined, Germany’s military leaders effectively engineered a situation where preventative war seemed the only option.

The German officer corps and General Staff became fixated on offensive operations, a phenomenon later termed the “Cult of the Offensive.” Despite advances in technology favoring defensive tactics, Germany's military leadership remained committed to strategies that emphasized rapid, aggressive action to avoid prolonged conflict. This mindset became deeply entrenched due to the isolation of the military from meaningful civilian oversight. Historian Jack Snyder's analysis of the period highlights how the lack of civilian control allowed military organizations to prioritize their own goals—prestige, autonomy, and control over strategic decisions—over broader state interests. This rigidity and unwillingness to adapt would contribute to the catastrophic outcomes of World War I.

The German naval buildup under Admiral Tirpitz, driven by a belief that a powerful fleet would coerce Britain into alliance or deter it from war, ultimately proved a diplomatic miscalculation. While Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg and other German diplomats sought détente and cooperation with Britain, the relentless push for naval expansion alienated the British and precluded any meaningful agreement. Tirpitz’s “risk fleet” concept was based on the flawed assumption that Britain, concerned with its colonies, would avoid conflict with a strong German navy. However, this only fueled an arms race, undermining diplomatic efforts and driving Britain into closer alignment with France. Despite moments of opportunity for peace, the German military’s influence over foreign policy, compounded by the Kaiser’s support for Tirpitz, made compromise impossible. This militarization of foreign policy not only failed to achieve its objectives but also deepened Germany’s isolation, contributing to the eventual breakdown of relations that led to World War I.

The Kaiser’s reign, characterized by the erosion of civilian oversight and the unchecked rise of military influence, laid the groundwork for Germany’s fateful march toward catastrophe. The rigid focus on offensive military strategies, driven by a narrow and fatalistic worldview, blinded leadership to diplomatic alternatives and the shifting realities of modern warfare. In the absence of meaningful civilian control, Germany’s foreign policy was increasingly shaped by militarism and brinkmanship, with ambitions that outstripped its capacity for restraint or compromise. The naval arms race with Britain, the flawed Schlieffen Plan, and the relentless pursuit of preventative war were all manifestations of a system where the military, driven by prestige and a fear of decline, outmaneuvered civilian voices of caution. In the end, the inability to adapt to balance ambition with pragmatism, would not only bring about the destruction of Germany’s imperial ambitions but also set Europe ablaze in one of the deadliest conflicts in human history.

References

Evera, Stephen Van. 1984. "The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War." International Security, Vol. 9, No. 1 58-107.

Förster, Stig. 2013. "Dreams and Nightmares: German Military Leadership and the Images of Future Warfare, 1871-1914." In Anticipating Total War The German and American experiences, 1871-1914, 343-376. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kennedy, Paul M. 1984. "The First World War and the International Power System." International Security, Vol. 9, (1) 7-40.

Kissinger, Henry. 1995. Diplomacy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Kitchen, Martin. 1979. "The Traditions of German Strategic Thought." The International History Review , Apr., 1979, Vol. 1, No. 2 163-190.

Lieber, Keir A. 2007. "The New History of World War I and What It Means for International Relations Theory ." International Security 32 (2) 155-191.

Lynn-Jones, Sean M. 1986. "Détente and Deterrence: Anglo-German Relations, 1911-1914." International Security , Vol. 11, No. 2 121-150.

Maurer, John H. 1997. "Arms Control and the Anglo-German Naval Race before World War I: Lessons for Today?" Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 112, No. 2 285-306.

Mombauer, Annika. 2005. Helmuth von Moltke and the Origins of the First World War . Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Ritter, Gerhard. 1972. The Sword and the Scepter: The Problem of Militarism in Germany Coral Gables: University of Miami Press.

Röhl, John C. G. 2014. Kaiser Wilhelm II: A Concise Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rosinski, Herbert. 1976. "Scharnhorst to Schlieffen: The Rise and Decline of German Military Thought." Naval War College Review: Vol. 29 : No. 3 83-103.

Showalter, Dennis. 2016. Instrument of War: The German Army 1914-1918. New York: Osprey Publishing.

Jack Snyder, “Civil-Military Relations and the Cult of the Offensive, 1914 and 1984.” International Security 9 (1) (1984).

Rosinski, Herbert. "Scharnhorst to Schlieffen: The Rise and Decline of German Military Thought." Naval War College Review: Vol. 29: No. 3 (1976): 101.

Jack Snyder, “Civil-Military Relations and the Cult of the Offensive, 1914 and 1984.” International Security 9 (1) (1984).

Keir A. Lieber, "The New History of World War I and What It Means for International Relations Theory." International Security 32 (2) (2007): 161.

Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 168.

For more on ultranationalist critique of the German government see Stig Förster, Der Doppelte Militarismus: Die Deutsche Heeresrüstungspolitik Zwischen Status-Quo-Sicherung Und Aggression, 1890-1913, Institut Für Europäische Geschichte Mainz: Veröffentlichungen Des (F. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden, 1985).

For further detail, see Gerhard P. Gross, The Myth and Reality of German Warfare: Operational Thinking from Moltke the Elder to Heusinger.

Stig Förster, "Dreams and Nightmares: German Military Leadership and the Images of Future Warfare, 1871-1914." In Anticipating Total War, The German and American experiences, 1871-1914, 343-376 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2013), 347.

A preventative war, in this context, is a conflict initiated to preemptively counter an anticipated future threat or to prevent a rival power from becoming stronger in the long term.

Gerhard Ritter, The Sword and the Scepter: The Problem of Militarism in Germany (Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1973), vol. 1 of 4, 243.

For more on Imperial German military culture, see Isabel Hull, Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005).

John C. G. Röhl, Kaiser Wilhelm II: A Concise Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2014).

Negative power refers to the ability of an actor or group to block, veto, or prevent actions, decisions, or policies from being implemented, rather than directly initiating or shaping outcomes.

Ritter, Sword and Scepter, vol. 2 of 4, 123.

Ritter, Sword and Scepter, vol. 1 of 4, 174.

Ritter, Sword and Scepter, vol. 1 of 4, 197.

Ritter, Sword and Scepter, vol. 2 of 4, 131.

Annika Mombauer, Helmut von Moltke and the Origins of the First World War, 59.

Ritter, Sword and Scepter, vol. 2 of 4, 106.

For the standard treatment and original documents, see Gerhard Ritter, The Schlieffen Plan: Critique of a Myth (London, W.i.: Oswald Wolff, 1958).

For more recent research, see David T. Zabecki et al, The Schlieffen Plan: International Perspectives (University Press of Kentucky, 2014).

Kissinger, Diplomacy, 205.

For more on the Schlieffen Plan, see Zabecki, David T. The Schlieffen Plan: International Perspectives on the German Strategy for World War I, (Lexington, University Press of Kentucky, 2014) and Arden Bucholz, Moltke, Schlieffen, and Prussian War Planning (New York: Berg, 1991).

Ritter, Sword and the Scepter, vol. 2 of 4, 169.

Ritter, 17.

Stig Förster, "Dreams and Nightmares: German Military Leadership and the Images of Future Warfare, 1871-1914,” 364.

See Milan Vego, "German War Gaming," Naval War College Review: Vol. 65: No. 4, (2012): 1-42 for a brief history of German War gaming.

See Abe Greenberg “AN OUTLINE OF WARGAMING.” Naval War College Review 34, No. 5 (1981): 93-97 for a brief historical overview and contemporary uses of wargaming.

Stephen Van Evera, "The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War." International Security, Vol. 9, No. 1 (1984): 58-107.

Jack Snyder. "Civil-Military Relations and the Cult of the Offensive, 1914 and 1984." International Security 9 (1) (1984): 110.

In Förster, 355-356.

Snyder, 117. See Friedrich von Bernhardi, On War of Today (London: Rees, 1912) for some of this criticism in detail.

Snyder, “Civil-Military Relations,” 119.

Kitchen, "The Traditions of German Strategic Thought," 39.

Kissinger, Diplomacy, 186.

Kissinger, 187.

Ritter, 149.

Ritter, 138.

Lynn-Jones, Sean M. "Détente and Deterrence: Anglo-German Relations, 1911-1914." International Security, Vol. 11, No. 2 (1986): 126.

Maurer, John H. "Arms Control and the Anglo-German Naval Race before World War I: Lessons for Today?" Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 112, No. 2 1(997): 287.

Ritter, 166.

Ritter, 163.

Ritter, 166.

Helmuth von Moltke the Elder was his uncle.

Mombauer, Moltke, 109.

Better known for other work.

Mombauer, 96.

Mombauer, 219.

Rosinski, “Scharnhorst to Schlieffen,” 99.

This section “The Cult of the Offensive and Wargaming “.

I may see something there that my mind put there, so I may or may not see what you did there- but the vices therein could quite apply not to the military but civilian leadership of my lifetime (the military leadership of my time from Powell to Milley) has been rather warning and reluctant, the Civilian Leadership has met few cults it didn’t embrace. After initial success and victory has been our inevitable destruction .

Thank you

This is fascinating, within two comments we have two complete oposing oppinion of the same person Wihl 2. I rembember discussing in school how much Bethman Holweg was to blame. Reading here he might as well tried to improve the time tables of the Berlin bus company.